Explore the African American Heritage Trail

Why Mount Auburn Cemetery?

At the consecration of Mount Auburn Cemetery overlooking the dell on a cloudless September day in 1831, Mount Auburn’s first president Justice Joseph Story spoke of the spiritual offerings of the new rural cemetery. “The grave hath a voice of eloquence, nay, of superhuman eloquence,” he wrote, “which calls up the images of the illustrious dead . . . for our example and glory.”[1] The Black men and women represented on Mount Auburn’s African American Heritage Trail evoke Story’s spirit of human eloquence: freedom seekers and reformers, lawyers and legislators, athletes and business owners, musicians and authors. All born in the 1800s, these individuals achieved extraordinary success in politics, business, literature, and the arts. Their resolve and strength were sustained by a richly interwoven community of family, friends, and associates.

"History is a clock that people use to tell their time of day. It is a compass that they use to find themselves on the map of human geography. It also tells them where they are, and what they are . . . . where they still must go, and what they still must be."

John Henrik Clarke,“Why Africana History?”

The Black Collegian, 1997

Why did these individuals chose to be buried at Mount Auburn? Founded as a nondenominational cemetery, it welcomed all faiths, races, and ethnicities from the time it first opened its gates. In 1864, an individual wrote to the weekly magazine, The Living Age, to inquire about the Cemetery’s policy on burying African Americans, having been told that “no other cemetery allows it.”[2] Mount Auburn’s Treasurer, George William Bond, responded that such policies “astonished” him, and that in regard to Mount Auburn, “In no case have I ever known an objection to be suggested.”[3] Edward Everett, president of Harvard and a trustee of Mount Auburn Cemetery, encouraged everyone, regardless of economic status, to consider the Cemetery. “Here it will be in the power of every one, who may wish . . . to deposit the mortal remains of his friends,” he wrote in 1832, “and to provide a place of burial for himself . . . surrounded with everything that can fill the heart with tender and respectful emotions; beneath the shade of a venerable tree, on the slope of the verdant lawn, and within the seclusion of the forest.”[4]

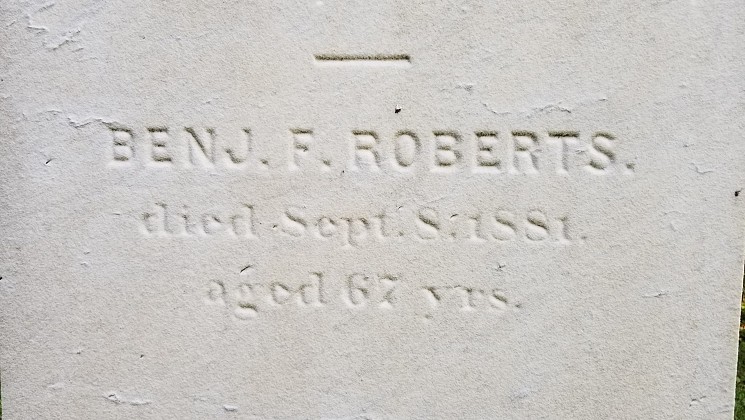

In contrast to other cemeteries that often set aside separate areas for African American burials, the graves of Blacks at Mount Auburn were not restricted to a single section. Rather they are located throughout the Cemetery’s grounds, reflective of its inclusive mission. Memorials are situated in family lots or at single gravesites. Some lots are embellished with ornate monuments or simple stones, others with no markers at all. In many cases, a monument may be the last surviving physical connection to an individual. A number of memorials on the African American Heritage Trail have suffered from years of exposure to the harsh New England weather. Fortunately, the Trail has inspired donations from individuals and organizations for the continued preservation of these monuments. Some are in need of washing and setting, while others require more costly conservation.

The sacred landscape of Mount Auburn was designed to commemorate the deceased and to provide visitors with a place for solace and inspiration. “It is to the living mourner . . . that the repositories of the dead bring home thoughts full of admonition, of instruction,” Joseph Story reflected. “They instruct us in the true value of life, and in its noble purposes, its duties, and its destination.”[5] The African Americans buried at Mount Auburn represent a rich mosaic of individuals, who advanced the opportunities for Blacks in the antebellum and post-war eras. Their lives tell a regional, national, and profoundly universal story.

This project has generated interest from scholars, researchers, and family descendants, who have deepened our knowledge of the African Americans buried at Mount Auburn. This first iteration of the Cemetery’s African American Heritage Trail, which includes those born in the nineteenth century, is the beginning of a story that will continue to unfold as scholarship continues and as the memorials of other individuals are added to the Trail.

The Enduring Bonds of Family

Freedom Seekers are among the Black individuals buried and remembered at Mount Auburn. Enslaved from the time of their birth, these men and women acted to make their dreams of freedom a reality. Their personal histories include the horrific experiences they endured in bondage, the extraordinary accomplishments they achieved as free men and women, and the deep family connections they held sacred throughout their lives. Buried at Mount Auburn, they came to rest with loved ones and among a community of those who supported their families’ fight for freedom.

A Symbol of the Cause

In 1831, the year of Mount Auburn’s founding, Henry A. S. Dearborn, one of Mount Auburn’s founders and designers, wrote that at the new cemetery “there will repose the ashes of the humble and exalted, in the silent and sacred Garden of the Dead.”[1] In the years that followed, among its hills and valleys, meadows and ponds, the Cemetery became a cultural landscape of memorials dedicated to the dead and in some cases the causes important to them. The monument for freedom seeker Peter Byus, a symbol of the abolitionist cause, has inspired visitors to the Cemetery since the 19th century.

Reformers and Their Community

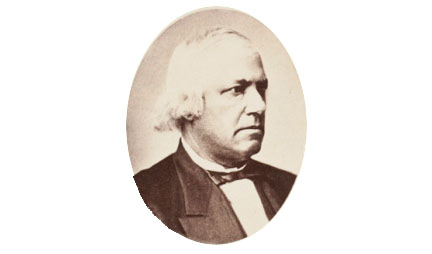

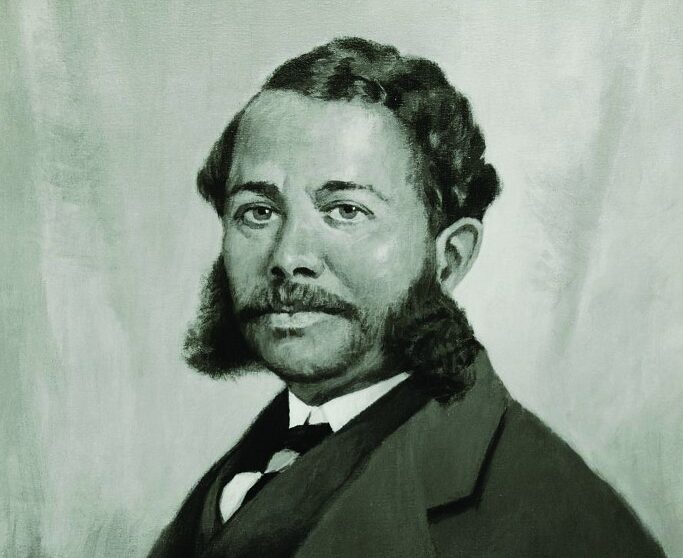

Along with Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia, Boston was a focal center of the abolitionist movement. Many of the local individuals who were part of this extensive network are now buried at Mount Auburn. Born in the early nineteenth century as free men and women, Benjamin Roberts, Joshua Smith, and Josephine Ruffin established their own entrepreneurial enterprises and worked tirelessly to secure freedom and equality for all African Americans.

Harvard and the Law

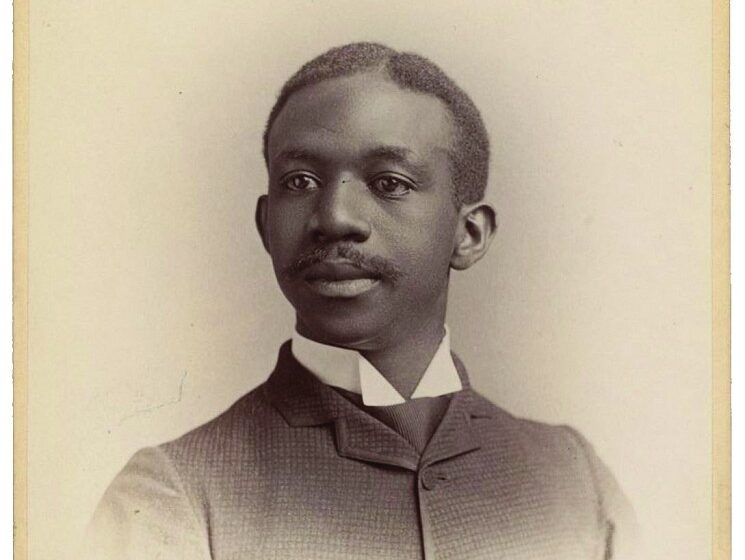

The Cemetery historically shared deep connections with Harvard University. “The vicinity of our venerable University suggests an interesting train of associations, connected with this spot,” Harvard President and Mount Auburn Trustee Edward Everett explained. “It has ever been the favorite resort of the students. . . . It will become the place of burial for the University.”[1] Harvard faculty and graduates who have since been buried at Mount Auburn include noted abolitionists Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, James Russell Lowell, Henry Ware, Joseph Story, and Charles Sumner. It was also here that George Ruffin, Clement Morgan, and William Henry Lewis, among the early African American graduates from Harvard Law School, came to rest.

Rediscovered Souls

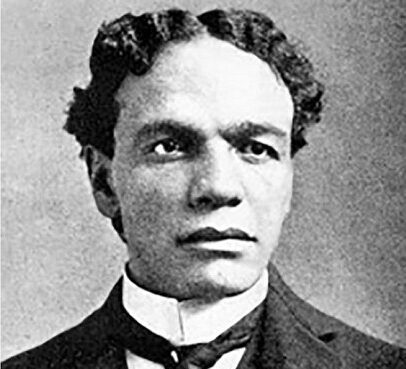

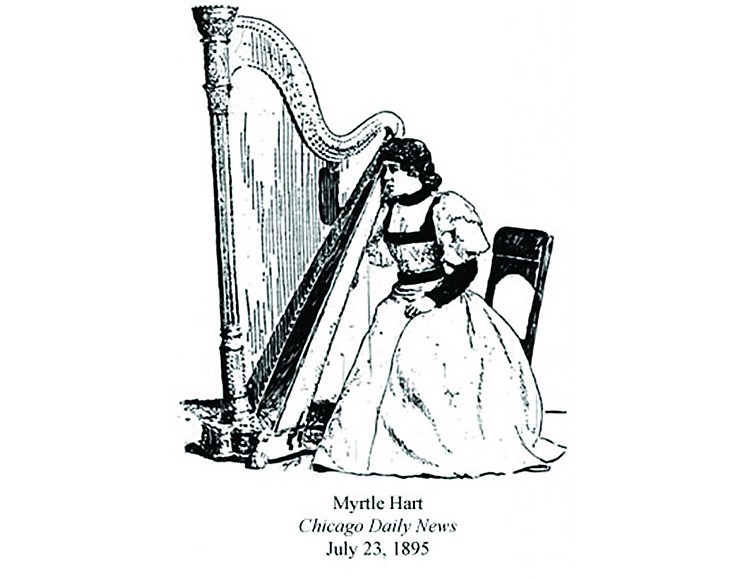

Within Mount Auburn are the gravesites of those who have only recently received the recognition that they deserve. Katherine Knox and Myrtle Hart, a bicyclist and a harpist, both blessed with talent, rose to the top of their professions. More recent efforts to celebrate the accomplishments of Clement Morgan have also brought to light the stories of his wife, Gertrude Wright and their close friend Adina White. We are grateful to the scholars and family members who introduced us to these four incredible women while researching Mount Auburn’s records.

Cemetery Icons

In addition to the gravesites of individual African Americans buried at Mount Auburn, monuments throughout the Cemetery stand as reminders of a community that fought for racial justice. They include memorials to Charles Sumner, Julia Ward Howe, and George Luther Stearns, white men and women who gave their hearts and souls to the abolitionist movement. Memorials that rank among the Cemetery’s most iconic symbols also tell this story: the statue Hygeia, by Edmonia Lewis, the great nineteenth-century African American sculptor; the memorial to Rev. Charles Turner Torrey, an abolitionist and “martyr to freedom”; the cenotaph of Col. Robert Gould Shaw, who led the 54th Massachusetts Regiment; and the Sphinx, the Cemetery’s magnificent memorial to the Civil War.

"A cemetery ought to be a place where the living and the dead mix on happy and useful terms. This is described as a place of repose and so it is, but it is also a place of purpose, and that purpose celebrates life and beauty, nature and the mysteries of God, which the theologians themselves cannot even begin to express or understand. It is a splendid enterprise."

The Reverend Peter Gomes, Plummer Professor of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister at The Memorial Church, Harvard University, speaking at the 175th Anniversary of Mount Auburn’s Consecration,

September 24, 2006.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project has been provided by the 1772 Foundation; Mass Humanities; the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (made possible by the National Park Service, National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom); the Cambridge Arts Council and the Watertown Cultural Council (local agencies supported by the Massachusetts Cultural Council, a state agency); and contributions from Sydney Nathans, Mary K. Zervigon, and the family of Katherine Knox.

Footnotes:

1 Joseph Story, “An Address Delivered on the Dedication of the Cemetery At Mount Auburn, September 24th, 1831,” in Jacob Bigelow, A History of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn, Boston: J. Munroe and Company, 1860, pp. 156-157.

2 Correspondence in The Living Age, Vol. 81, No. 1039, April 1864, in E. Little, The Living Age, Third Series, Volume XXV, Boston: Little, Son, and Company, p. 193.

3 Ibid.

4 Edward Everett in Horticultural Proceedings, 1832, in Jacob Bigelow, A History of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn, Boston: J. Munroe and Company, 1860, pp. 138-139.

5 Joseph Story, “An Address,” pp. 147-148.

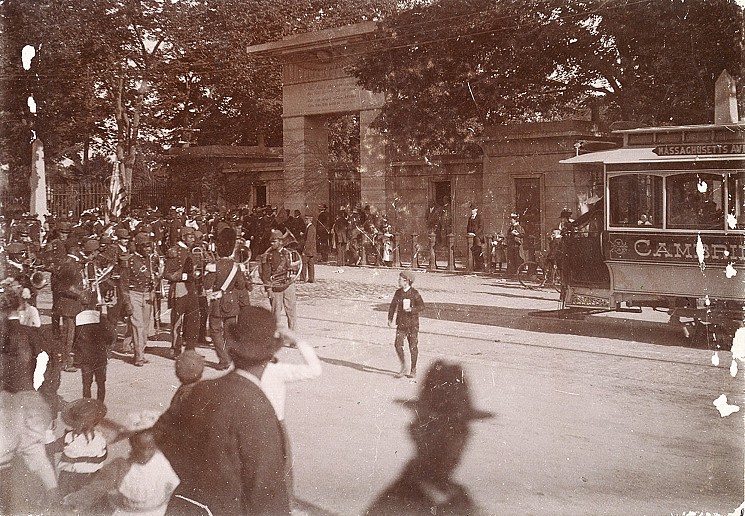

Top Image:

Visitors including African American musicians gathering in front of Mount Auburn’s Egyptian Revival Gateway, ca. 1870-1900 cabinet card. Historical Collections, Mount Auburn Cemetery.