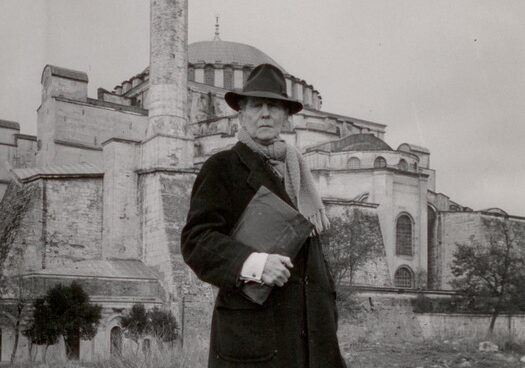

Thomas Whittemore (1871 – 1950)

Scholar & Archaeologist

by Robin Hazard Ray

The late Thomas Whittemore (1871–1950, Sorrel Path 2007) defies definition. The Dictionary of Art Historians describes him as a “Harvard Byzantinist and Egyptologist.”[1] Art scholar Holger A. Klein, in his article “The Elusive Mr. Whittemore,” calls him a “Boston-born English professor, archaeologist and charismatic founder of the Byzantine Institute of America.”[2] None of these descriptors begins to encompass the astonishing range of his activities and interests. For example, he brokered the 1929 deal whereby the Soviet Union sold Harvard the holy bells of Moscow’s Danilov Monastery for gold, saving the bells from the smelter.[3] How would one describe that job: bell-rescuer/bullion smuggler?

But unarguably greatest work of his life—the uncovering of the magnificent Byzantine mosaics of the Hagia Sophia Basilica in Istanbul, built in the 6th century C.E. by the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I—now stands in jeopardy. A Turkish court recently permitted Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to revoke the building’s status as a museum, opening it to Muslim prayer.[4] The decision has been received with consternation among Orthodox Christians and art historians, but has been hailed by “Islamists and pan-Turkic romanticists” as redress for a century of Western-imposed secularization on a building that had functioned for centuries as a mosque.[5]

Little in the early years of Whittemore’s life would have foreshadowed a future of globe-trotting, adventure, and intrigue. He graduated from Tufts University in 1894, staying on to teach English and, later, art history. He studied art history at Harvard, where he met and befriended Gertrude Stein.

He was a deeply religious man who turned from the Universalist roots of his family. (His grandfather and namesake Thomas Whittemore [1800–1861] was an influential Universalist author.) He became an Anglo-Catholic—a high-ritual branch of Episcopalianism, centered in Boston at the Church of the Advent—a bent that he shared with his friend Isabella Stewart Gardner (1840–1924, 2900–1 Oxalis Path). His attraction to the sensual aspects of Christian worship—incense, music, architecture—may have led his career toward the Byzantine and Orthodox Christianity.

Whittemore’s quiet scholarly life changed abruptly with the death of his widowed mother, Elizabeth St. Clair Whittemore, in 1904. An only child, Whittemore inherited a house in Cambridgeport (no longer standing) and presumably enough money to abandon his teaching career. With nothing left to tie him down in Boston, he took up a life of ceaseless travel and inquiry. He hopped back and forth between Eurasia, Africa, and America over the next decades, turning up occasionally as a docent in the Egyptian Department at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts or teaching a class at Harvard; just as often he was heard from assisting refugees in Galicia or socializing with Coptic clergy in Cairo. In Paris in the first decade of the twentieth century, he alighted temporarily in the circle of Gertrude Stein and her partner Alice B. Toklas. His friend (and possibly lover) Matthew S. Prichard (1865–1936), through whom Whittemore met and befriended the painter Henri Matisse, complained in a letter to Belle Gardner: “Whittemore is never in a place; he was, he will be; he comes from and is going to; but he is never ‘here.’”[6]

He knew dozens of languages, including (at least) Greek, Latin, all major European modern languages, Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Arabic, Turkish, Coptic, and Egyptian hieroglyphics. The novelist Graham Greene, who met the professor on a ship convoying from Britain to Africa in 1941, wrote in his diary: “Whittemore seems to know all languages.”[7] Another twentieth-century writer, Evelyn Waugh, met Whittemore while attending the 1930 coronation of Emperor Haile Selassie in Abyssinia (now Ethiopia); Waugh’s detailed description of the junket he and Whittemore took to visit the remote Coptic monastery of Debra Lebanos is a classic of travel literature.[8] It gives us a sense of the intrepidity of Whittemore, who was then nearly sixty years old: bouncing for hours over washed-out roads, sleeping on piles of hay and carpets in a freezing tent, just to gaze on the buildings and relics of an ancient Christian redoubt.

Though his struggling biographers have called him “professor,” “archaeologist,” and “Byzantine expert,” Whittemore’s true genius was not scholarly. He wrote very little of substance in his long life, and much of what he did write has been dismissed by specialists as amateurish. Instead, his great gift was for friendship and connection. In turn, he coaxed his friends and acquaintances into supporting, either financially or politically, the many and diverse projects to which he turned his restless mind.

One of his projects, begun in the 1920s as the modern state of Turkey was taking shape, was to survey the grounds of the grand mosque that had inhabited the former basilica of Hagia Sophia in Istanbul (Constantinople). Whittemore knew that the basilica had once been adorned with glorious mosaics depicting the lives and miracles of prophets and saints. But these mosaics had been plastered over after the Turkish conquest of Constantinople in 1453, so that Muslim worshipers in the space would not be offended by their imagery. With gentle persistence, putting the case to every archaeologist and official he met in Istanbul, Whittemore gradually worked his way up the chain of power to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the former field marshal who had become the first president of the Republic of Turkey in 1923. At Whittemore’s suggestion, Atatürk opened the basilica as a museum in 1935 and approved the restoration of its great mosaic cycles.

Whittemore spent the last two decades of his life, from 1929 until his sudden death in 1950, restoring and studying the mosaics which, in scale and beauty, have no equal in the world. Tirelessly he worked to maintain good relations with officials of the Turkish government, and just as tirelessly he raised funds for the restoration work among his many wealthy American acquaintances.

He loved Istanbul. In a beautiful letter written to Isabella Stewart Gardner at the end of her life, when she had been rendered an invalid by a series of strokes, he wrote:

I wonder if you have ever been in Constantinople during Ramazan [Ramadan]; among these beautiful nights I think of you very often. Beneath my window lies the Golden Horn; from its flaring end at the old bridge to its delicate mouth-piece at Eyoub. I raise it to the lips of my imagination and sound it for you to hear. Around me as far as I can see, to the long line of the Marmara is a garden of mosques . . .The minarets are like night-blooming-cereus, in their mysterious and solitary flowering, which fade dawn-struck.”

In the same latter, he eulogizes the basilica: “Sancta-Sophia is a sphere of light. It is the universe of buildings. Sancta Sophia: Holy Wisdom. It is what the world most needs and has lost.”[9]

It is hard to predict how the mosaics of Hagia Sophia will fare now that the building is once again a mosque. The treatment of Byzantine mosaics in other buildings that have returned to Muslim worship under the current Turkish administration do not leave one optimistic.[10] Perhaps another figure will emerge with the energy of Thomas Whittemore to help Hagia Sophia through its current transition. But there will certainly never be another Thomas Whittemore.

Thomas Whittemore is buried next to his parents, Joseph and Elizabeth St. Clair Whittemore, though his grave bears no marker. Lot 2007, Sorrel Path.

Footnotes:

[1] https://arthistorians.info/whittemoret

[2] Holger A. Klein, ““Tarifi Zor Bay Whittemore: Erken Dönem, 1871–1916” [The elusive Mr. Whittemore: The early years, 1871–1916], in The Kariye Camii Reconsidered, ed. by Holger Klein, Robert Ousterhout, and Brigitte Pitarakis (Istanbul, 2011), 468.

[3] Robert S. Nelson, Hagia Sophia, 1850–1950: Holy Wisdom Modern Monument (Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 2004), 173.

[4] Sarah Cascone, “A Turkish Court Has Revoked the Hagia Sophia’s Status as a Museum,” ArtNews (10 July 2020). https://news.artnet.com/art-world/hagia-sophia-mosque-museum-1893761

[5] Selim Koru, “Turkey’s Islamist Dream Finally Becomes a Reality,” New York Times (14 July 2020).

[6] Prichard to Isabella Stewart Gardner, letter dated 5 July 1924, Klein, “The Elusive Mr. Whittemore,” 467. This letter, dated less than 2 weeks before Gardner’s death, may have been one of the last letters she received.

[7] Graham Greene, In Search of a Character: Two African Journals (New York: Viking, 1994), 76.

[8] Evelyn Waugh, “A Coronation in 1930,” in When the Getting Was Good (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1946), 103–121.

[9] TW to ISG, 6 July 1920; excerpted in Nelson, Hagia Sophia, 170.

Top Image:

Thomas Wittemore in front of the Hagia Sophia. Photograph by Dimitri Kessel (1902–1995), Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.