The Genesis of The Experimental Garden at Mount Auburn Cemetery

Melissa Banta May 3, 2022 History

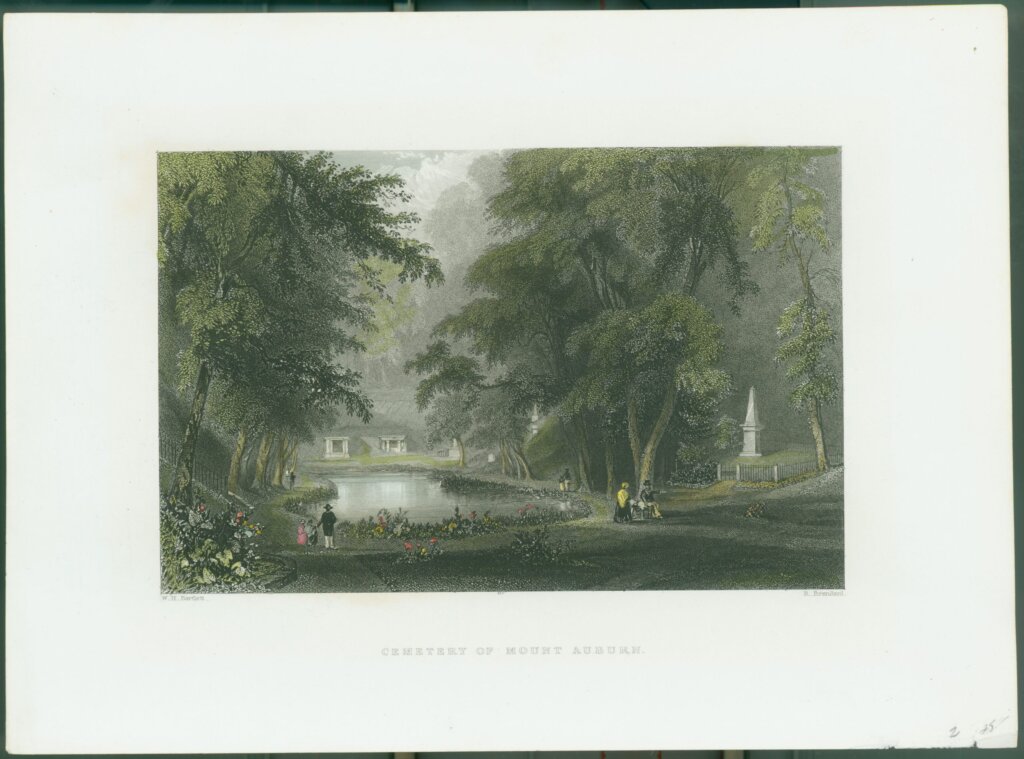

Mount Auburn was born from the marriage of two ideas: an ornamental cemetery for the commemoration of the dead and an experimental garden in which to practice the art and science of horticulture.1 The Cemetery’s founders were members of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, established in 1829. The Garden and Cemetery Committee, formed by the Society to investigate the creation of a garden and cemetery, made critical decisions in the initial design and development of Mount Auburn. Early records referred to the site as “the Experimental Garden and Cemetery of Mount Auburn.”

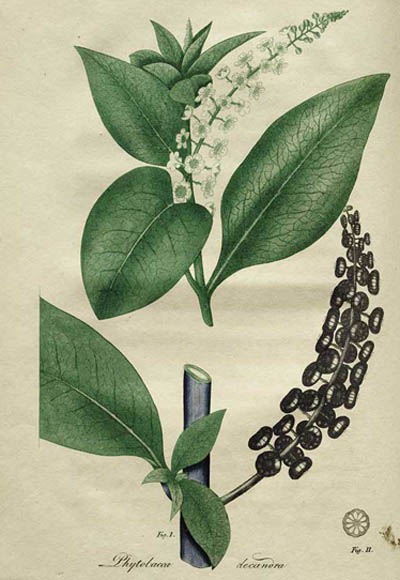

Mid-nineteenth century New England was experiencing a revival of interest in the cultivation of gardens.2 Although Boston was becoming increasingly populated, the adjacent areas were still rural in character and home to a number of large country estates. The statesman Henry A. S. Dearborn, for example, founder and first president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and enthusiastic advocate for the development of an experimental garden and cemetery, owned a country estate in Roxbury, where he practiced horticulture. Jacob Bigelow, a physician at Harvard Medical School and another principal founder of Mount Auburn, had an ardent interest in botany. His books include Florula Bostoniensis. a Collection of Plants of Boston and Its Vicinity, a valuable manual on plants in the area, and American Medical Botany, with botanical illustrations by Bigelow.

“The core of supporters . . . for a rural cemetery and experimental garden were all people with a shared passion for science and a robust intellectual vigor,” writes Dennis Collins, Horticultural Curator of Mount Auburn.3 The Horticultural Society’s members included statesmen, industrialists, merchants, lawyers, and doctors representing the Boston elite as well as practicing horticulturalists including botanists, farmers, gardeners, nursery owners, and seed traders.

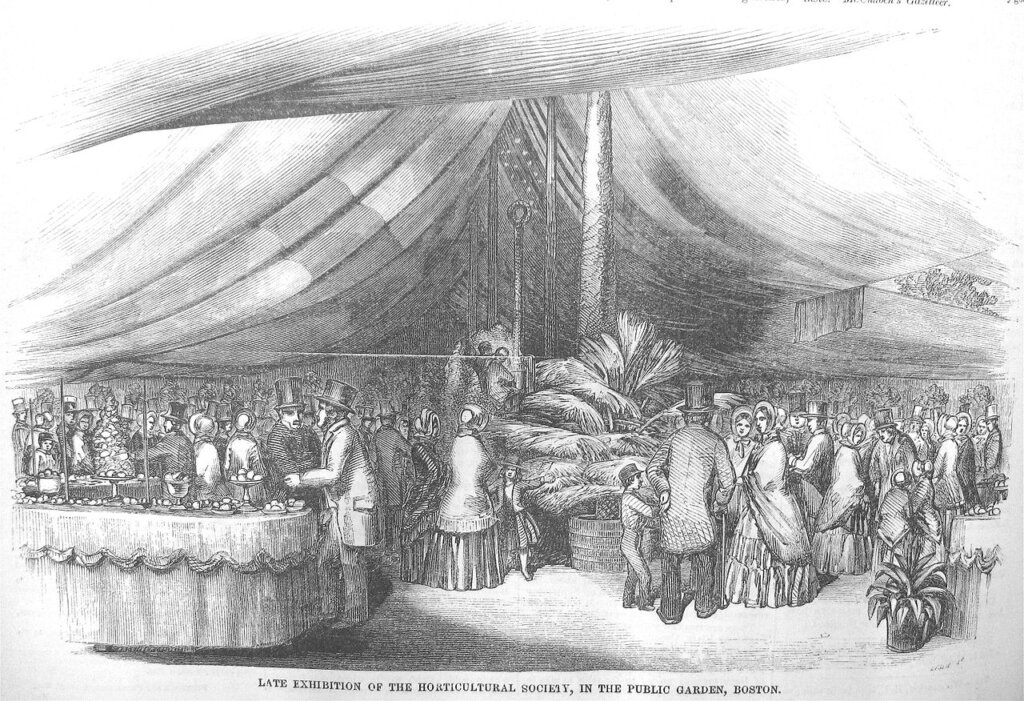

The Society modeled itself after the Horticultural Society of London founded in 1804 (later the Royal Horticultural Society). Members of the Massachusetts society admired other “experimental gardens” and “experimentalists” in France and England, with whom they corresponded.4 “By emulating their zeal, intelligence, and experimental industry,” the Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society noted, “ . . . we must develop the resources of our own country, which offers such an extensive, interesting, and prolific field of research to the adventurous naturalist.”5 The Society’s activities included the exchange of books, seeds, and plants; the building of a library with volumes on English and French horticulture; the exhibition of fruits, flowers, and vegetables; and the dissemination of information through meetings, scientific papers, and publications such as the New England Farmer. Dearborn even contemplated building a Botanical Garden and an Institution for Education of Scientific and Practical Gardeners. “An interest has been excited,” Dearborn wrote, “and a spirit of inquiry awakened, auspicious to the institution, while a powerful impulse has been given to all branches of rural industry, far beyond our most sanguine hopes.”6

The Society laid out its vision for the Experimental Garden at Mount Auburn:

The objects which will chiefly claim attention, are the collection and cultivation of common, improved, and new varieties of the different kinds of Fruits, Esculent Vegetables, Forest and Ornamental Trees and Shrubs, Flowering, Economical, and other interesting Plants . . . paying particular attention to the qualities and habits of each; instituting comparative experiments, on the modes of culture, to which they are usually subjected, so as to attain a knowledge of the most useful, rare, and beautiful species; —the best process of rearing and propagating them by seeds, scions, buds, suckers, layers, and cuttings;—the most successful methods of insuring perfect and abundant crops, as well as satisfactory results, in all the branches of useful and ornamental planting appertaining to horticulture.7

The Society considered the establishment of the Experimental Garden “indispensable to the full development of [its] purposes,” and believed the combination of the Garden and Cemetery would “assist in improving the taste of the public in this highest branch of the art of horticulture.”8 As visitors to Mount Auburn would come to know about the lives of those in the young country commemorated in the Cemetery, they would also learn about the art and science of horticulture. The combination of an Experimental Garden and Cemetery would promote the Society’s ideas about the moral and purifying aspects of horticulture as well. Zebedee Cook, Jr., vice president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, wrote that in the new site “Nature [would open] a never-failing paradise to those who are content to be innocent and well-employed” and the soul would be “subdued, and the affections purified and exalted.”9

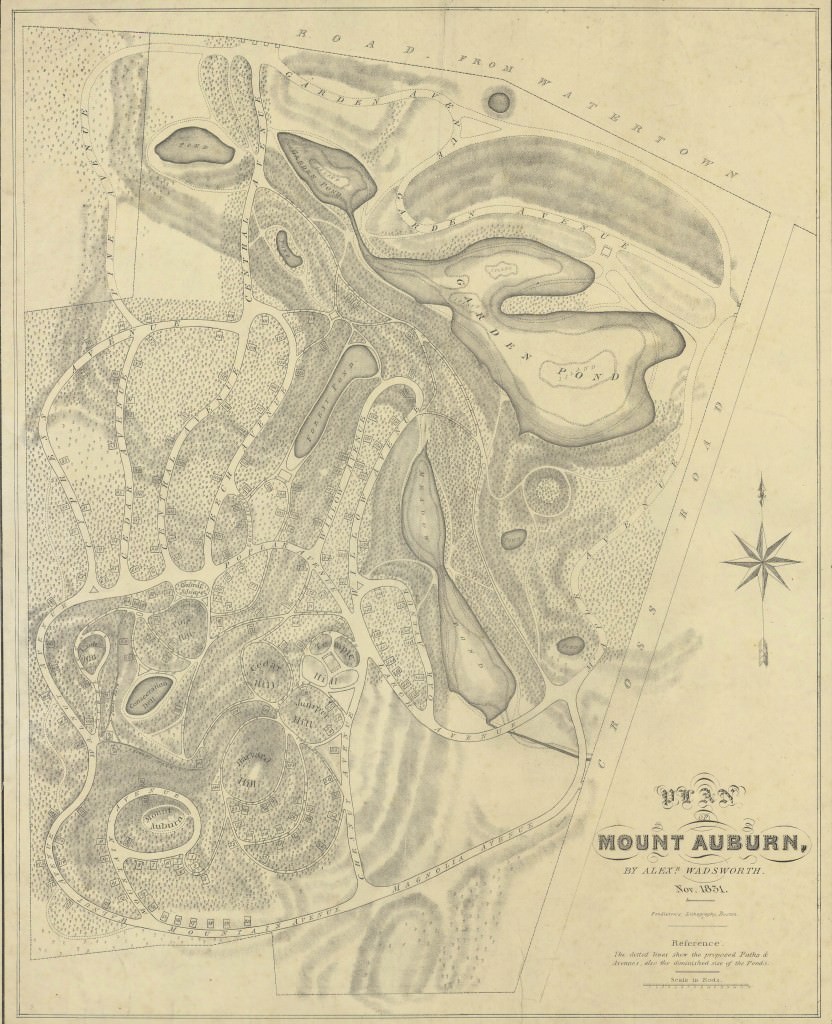

When Massachusetts Horticultural Society purchased 72 acres of land for Mount Auburn in 1831, they set aside 32 acres for the Experimental Garden. The Garden and Cemetery Committee placed the Garden in the northeastern section of the Cemetery, east of Central Avenue near the largest of the ponds, Garden Pond (known today as Halcyon Lake). The area, where the Trustees stipulated no lots would be sold, also afforded a buffer between the public road and burial lots. Dearborn planned for the ornamental grounds of both the Garden and the Cemetery to be “blended, and the walks so intercommunicate as to afford an uninterrupted range over both, as one common domain.”10

In 1833, the trustees of Mount Auburn created the position of superintendent and gardener to oversee both the operations of the Cemetery and the cultivation of the Garden. They chose highly skilled horticulturalists for the position. The first superintendent and gardener, David Haggerston, learned the art of horticulture in England from his father.11 Upon his arrival in Massachusetts, he worked on the estate of Governor Gore in Waltham and then operated a successful nursery in Charlestown known as the Charlestown Vineyard. John Russell became Mount Auburn’s second superintendent and gardener in 1834. Also from England, he worked on the country estate of the Duke of Westminster before coming to Boston, where he found a position with Haggerston at the Charlestown Vineyard. Members of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, both men contributed regularly to horticultural publications such as American Gardener Magazine.

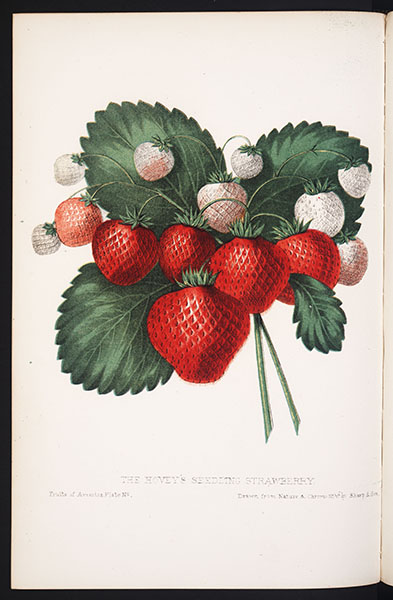

The Experimental Garden provided the Society the opportunity to cultivate and exchange domestic and foreign varieties of fruits, flowers, vegetables, and plants and to conduct horticultural experiments. The Society often received donations of seeds from horticulturalists, botanists, and gardeners around the world, which they distributed among its members. It now entrusted many of these donations to Mount Auburn for use in the Experimental Garden. Haggerston and Russell also exhibited vegetables, fruits, and flowers from the Garden in the Massachusetts Horticultural Society exhibition halls.12 These weekly exhibits, open to the public, provided an educational opportunity to share horticultural techniques and innovations, and the Society awarded prizes to the best species and exhibits.

As Dearborn reported:

I am happy to announce to the Society that the plan of the experimental garden at Mount Auburn is in progress, and will soon be carried completely to effect. Mr. Haggerston, the gardener, moved into the cottage early last month, and with two laborers, has been constantly and industriously employed in setting out over one thousand and three hundred forest, ornamental, and fruit trees, planting culinary vegetables, and preparing hotbeds for receiving a great variety of useful plants, which are intended to be distributed over the various compartments of the garden, and on the borders of the avenues and paths. Among the seeds planted are four hundred and fifty varieties which have been sent to the society from Europe, Asia, and South America.13

Soil from the clearing of the ponds was added to the Garden to make the area more suitable for the cultivation of trees and shrubs. Haggerston and Russell grew flowering plants for use as ornamentation of the grounds and along the avenues and path, to which Bigelow assigned botanical names. The Cemetery kept a record of all seeds, plants, and trees received, their species, and from whom and where they came as well as “all monies produced by the sale of flowers, plants, shrubs, and trees from the said Garden.”14 Among the plants cultivated were magnolias, petunias, delphiniums, asters, radish, cauliflower, broccoli, peas, beans, melons, and strawberries. Dennis Collins explains, “The most exotic source might have been the Botanical Society of the Kingdom of Naples, and perhaps one of the more recognizable exotic plants was the Guul ibrischim or ‘silk tassel rose’ sent from Turkey.”15 While members of the Garden and Cemetery Committee championed the exchange of plants with other countries, they also saw the role of the Experimental Garden in helping to develop “the vast vegetable resources of the Union,―give activity to enterprise,―increase the enjoyment of all classes of citizens,―advance the prosperity, and improve the general aspect of the whole country.”16

By September 1834, Mount Auburn had sold 351 lots, and proceeds from the sales helped cover the expenses of the Garden and the Cemetery. Proprietors of burial lots automatically received a lifetime membership in the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and a controlling vote in the Society’s affairs.17 As the number of lot owners increased, differing priorities arose over the expense of maintaining both the Cemetery and the Garden.18 The History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society observed that many lot owners may have felt “an indifference, if not a positive aversion, to the idea of an experimental garden.”19

In 1834, the Cemetery established a committee to investigate how “to render the garden productive and profitable.”20 Mount Auburn trustees Joseph P. Bradlee and Elijah Vose, who was vice-president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and later president, submitted a detailed report on the state of the Garden. They offered strategies for making the Garden self-sustainable and profitable with the idea “to advance by degrees, with small expenditures, until it shall be made capable of furnishing not only all the trees, shrubs . . . wanted for the purposes of the Garden and Cemetery, but its surplus products be equivalent . . . to defraying the expenses of the labor of conducting it.”21 They expressed their hope that the Garden be considered “not only an object of interest and of utility but worthy of forming a part of the institution of Mount Auburn.”22

Tensions increased, however, over the expenses associated with the garden, and Mount Auburn began to face future capital expenditures, including in the 1840s, the replacement of the perimeter wooden fence with an iron fence and the building of Bigelow Chapel. The History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society noted that the “subject was much discussed both in and out of the meetings of the Society, considerable warmth of feeling being elicited among the friends of the two departments; and it became evident that a peaceful arrangement was not likely to be made, except by a sale of Mount Auburn, by the Horticultural Society, to a new corporation, to be composed of owners of the holders of lots.”23 Joseph Story, Mount Auburn’s first president and an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, presided over a committee to dispose of the interests of the Society.

In June 1835, the Proprietors of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn, a newly established entity, took over ownership of the Cemetery from the Society, and Mount Auburn no longer maintained the Garden.24 From 1835 until 1976, a percentage of funds from the sale of lots went to the Horticultural Society.25

“By putting the grave in the garden, Mount Auburn transformed American burial practices,” notes Meg Winslow, Curator of Historical Collections & Archives at Mount Auburn.26 While the Experimental Garden did not endure, the union of commemoration and horticulture manifested in a new America landscape. Collins explains that, “Each of the generations of horticulturalists, who have been the stewards of this landscape . . . has brought its own vision and innovative spirit to the task of building and improving Mount Auburn.”27 From the creation of 19th-century greenhouses to 21st-century climate action and sustainability programs, the Cemetery has remained dedicated to the advancement of the art and science of horticulture—as eloquently articulated in the founders’ vision of the Experimental Garden.28

Citations

1 “An Act to Incorporate the Proprietors of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn,” 1831, p. 6. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-005-001/display/1061993.

2 See Mary-Alice Rea, “Introduction of Economic Plants into New England,” Economic Botany, vol. 29, no. 4 (Oct. -Dec .1975), pp. 333-356.

3 Dennis Collins, “A History of Horticultural Innovation,” Sweet Auburn (Fall 2010), p. 1.

4 Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1838 (Boston: William D. Ticknor, 1847), p. 21.

5 Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1838, p. 21.

6 Henry A. S. Dearborn in Robert Manning, History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1878 (Boston: Rand, Avery, for the Society, 1880), p. 68.

7 Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, p. 64.

8 Manning, p. 76.

9 Zebedee Cook Jr., An Address Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in Commemoration of Its Second Annual Festival, the 10th of Sept., 1830 (Boston: Isaac R. Butts, 1830), pp. 27- 28.

10 Manning, p. 96.

11 Haggerston left Mount Auburn in 1834 to work on the vast estate of John Perkins Cushing in Belmont.

12 “Obituary, Death of David Haggerston,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, vol. 1863.

13 Dearborn in Manning, p. 98.

14 “Massachusetts Horticultural Society Contract with James W. Russell, 1834, p. 1. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1834-feb-06-contract-mhs-russell-jw-gardener/display/1218029.

15 The silk tassel rose is known today as “mimosa” (Albiizia julibrissin). Collins, p. 2.

16 “An Account of the Proceedings, In Relation to the Experimental Garden and the Cemetery of Mount Auburn,” Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1838, p. 65.

17 “An Act to Incorporate the Proprietors of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn,” 1831, p. 5. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-005-001/display/1061993.

18 Manning, p. 107.

19 Manning, pp. 101-102.

20 “Records of Committees,” Aug. 30, 1834, p. 23 and October 27, 1834, p. 24. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-003-001/display/1217964.

21 “Report on the Committee to Examine the Garden,” 1834, pp. 6-7. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-034-010/display/1218015.

22 “Report on the Committee to Examine the Garden,” 1834, p.7. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-034-010/display/1218016.

23 History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1878, p. 110.

24 Proprietors of new lots no longer received lifelong membership in the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, unless they applied individually to the Society. The Society gave the Proprietors of the Cemetery use of a room in one of its Horticultural Halls or its library for annual meetings. “Massachusetts Horticultural Society Agreement,” October 9, 1835. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-015-039/display/32046353.

25 In 1834, Henry A. S. Dearborn, resigned as president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. He went on to design Forest Hills Cemetery in Roxbury, where he was elected major. In later years, Bigelow, who served as second president of Mount Auburn from 1845 to 1871, distanced himself from association with the experimental garden.

26 Personal communication, Meg Winslow, 3/15/22.

27 Collins, p. 1.

28 In 2010, Mount Auburn staff created another Experimental Garden, known as the E-Garden, for the testing of new products, techniques, and plants for future use on the grounds.

Comments

Comments for this post are closed