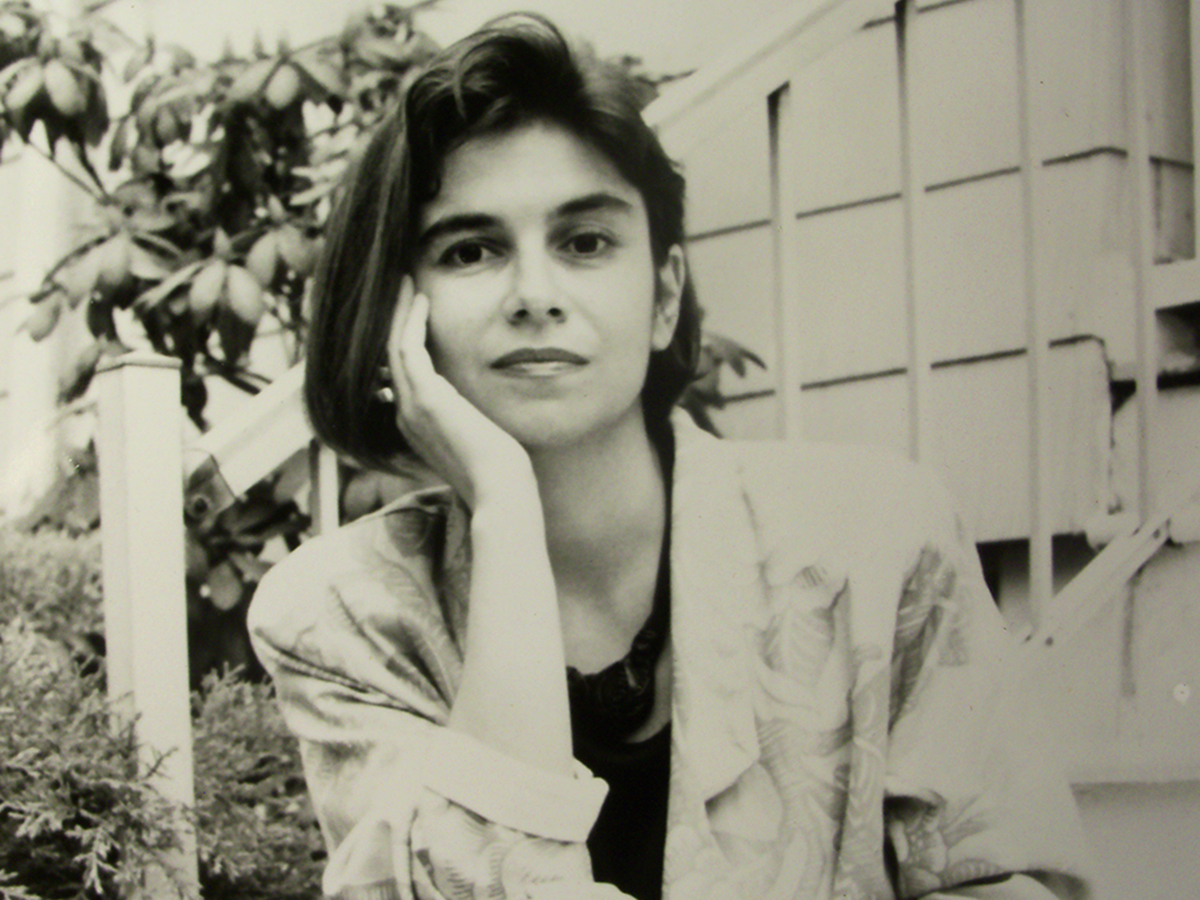

Svetlana Boym (1959-2015)

Novelist & New Media Artist

Svetlana Boym was born in Leningrad on April 29, 1959, and left the U.S.S.R. for the United States in 1980 at the age of 21. After graduate studies in Boston and Cambridge, MA, she became the Curt Hugo Reisinger Professor of Slavic and Comparative Literatures at Harvard University, as well as a novelist, playwright, cultural critic and new media artist.

Boym’s written work combined historical analysis, philosophical essay and personal memoir, exploring motifs of nostalgia, exile, freedom and memory, and most especially, the concept of the off-modern. Meanwhile, her scholarly research touched upon the diasporic imagination and revealed parallels and connections within and between the fields of comparative literature, cultural studies and 20th-century Russian literature.

A prolific scholar, her many academic publications include: The Future of Nostalgia, The Alternative History of an Idea, Death in Quotation Marks, and Common Places: Mythologies of Everyday Life in Russia.

She was awarded several prizes during her career, including a Guggenheim Fellowship, a Bunting Fellowship, the Cabot Award for Research in Humanities, a Gilette Company Fellowship and an award for mentoring students at Harvard.

Always interested in the arts as well as in history, Boym curated the exhibit “Territories of Terror: Memories and Mythologies of Gulag in Contemporary Russian-American Art” at Boston’s University Art Gallery in 2006, the same year her own exhibit of new media art opened during the City of Women Festival at the Factory Rog-Metelkovo, an art space in Ljubljana. She later exhibited her work at the Center for Book Arts in New York in 2008, and Galerija 101 in Kaunas in 2009 and participated in the 5th Moscow Biennale of Contemporary Art in 2013.

Ironic, witty, charming and exuberant Boym frequently gave scholarly talks around the world and was an extremely popular and charismatic professor at Harvard – with numerous well attended classes on art, literature and visual culture in the Soviet era. A few of her favorite writers were Akhmatova, Arendt, Benjamin, Brodsky, Dostoevsky, Mandelstahm, Nabokov, Pushkin and Shklovsky – and she explored their ideas in her books and in her classes with students.

In The Future of Nostalgia Boym quotes:

“I distinguish between two main types of nostalgia: the restorative and the reflective. Restorative nostalgia stresses nostos (home) and attempts a transhistorical reconstruction of the lost home. Reflective nostalgia thrives on algia (the longing itself) and delays the homecoming—wistfully,ironically, desperately. These distinctions are not absolute binaries, and one can surely make a more refined mapping of the grey areas on the outskirts of imaginary homelands. I want to identify the main tendencies and narrative structures in “plotting” nostalgia, in making sense of one’s longing and loss. Restorative nostalgia does not think of itself as nostalgia, but rather as truth and tradition. Reflective nostalgia dwells on the ambivalences of human longing and belonging and does not shy away from the contradictions of modernity. Restorative nostalgia protects the absolute truth, while reflective nostalgia calls it into doubt.”

“Nostalgia appears to be a longing for a place, but it is actually a yearning for a different time—the time of our childhood, the slower rhythms of our dreams. In a broader sense, nostalgia is a rebellion against the modern idea of time, the time of history and progress. The nostalgic desires to turn history into private or collective mythology, to revisit time like space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.”

She continued:

“While restorative nostalgia wishes to return / rebuild one’s homeland with paranoic determination, reflective nostalgia fears return with the same passion. Reflective nostalgia is concerned with historical and individual time, with the irrevocability of the past and human finitude. Re-flection means new flexibility, not the reestablishment of stasis. The focus here is not on the recovery of what is perceived to be an absolute truth, but on the meditation on history and the passage of time. Nostalgics of this kind are often, in the words of Vladimir Nabokov, “amateurs of Time, epicures of duration,” who resist the pressure of external efficiency and take sensual delight in the texture of time not measurable by clocks and calendars.”

Svetlana Boym died at the age of 56 on August 5, 2015 after nearly a year-long struggle with cancer. She is buried at Mount Auburn Cemetery on Mound Ave.

Footnotes:

This biography was written and researched by Jennifer Johnston.