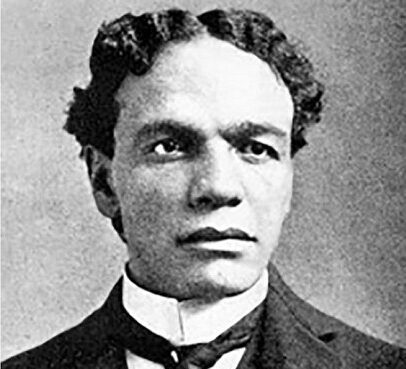

William Henry Lewis (1868-1949)

All-American Football Player & U.S. Assistant Attorney General

William Henry Lewis came from Berkeley, Virginia, born to parents who had been enslaved but later freed. He attended public school, and at age 15, entered the Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute for Blacks in Petersburg, Virginia. In 1888, he enrolled at Amherst College. While at Amherst, he worked as a stable groom for Rev. Julius H. Seelye, the college president, who gave the young student financial and emotional support.

Lewis’s scholarly and athletic talents made themselves evident at Amherst, where he achieved notice as an acclaimed debater and captain of the football team. He entered Harvard Law School, played two seasons of football, and became the first African American to be named to the All-American team. He coached football at Harvard from 1895 to 1906, one of the few African American coaches in an Ivy League college, and wrote A Primer of College Football. “Our race is proud of him because in all his success he stands for us,” the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Quarterly Review noted, “and the higher he goes in the physical field of athletics or the mental field of law or literature, he must necessarily open the way for others, and lift us all up at the same time.”[1]

After graduation from Harvard Law School in 1895, Lewis became a partner in the firm of Lewis, Fox, and Andrews. His interest in civil rights was ignited when in 1893, a barbershop refused to serve him. Lewis filed suit and was instrumental in extending the ban on discrimination more broadly in Massachusetts: from public transportation and public meetings, to theatres, skating rinks, barber shops, and public places for hire, gain, or reward.

Lewis married Elizabeth B. Baker, who had been a student at Wellesley College, and the couple lived on Upland Road in Cambridge, where they raised three children. In 1899, Lewis began to serve on the Cambridge Common Council, and in 1902 he was elected to the Massachusetts House of Representatives. His talents caught the attention of Theodore Roosevelt, who appointed Lewis assistant United States Attorney for Boston from 1903 to 1906 and then Assistant United States Attorney for immigration and naturalization for the New England States from 1907 to 1911. In 1911, he became Assistant Attorney General of the United States under President Taft, the highest federal position to which an African American had ever been appointed.

Lewis faced discrimination again when he was admitted to the American Bar Association, which, after his race was revealed, revoked Lewis’s membership. At the convention the following year, Attorney General George W. Wickersham supported the reinstatement of Lewis, who became one of the first three African Americans to become a member of the American Bar Association. In 1913, Lewis established a law firm with Matthew L. McGarth where he became known for helping clients receive less than the maximum penalty. The New York Times praised his “natural genius as an orator,” and the author and minister William Ferris depicted Lewis as “a second Daniel Webster” and “a man whose eloquence is irresistible.”[2]

When the noted abolitionist Julia Ward Howe died in 1910, Lewis was one of three speakers at her memorial service in Symphony Hall. Howe, like many other abolitionists in Lewis’s circle of friends, was buried at Mount Auburn. Lewis purchased a family lot at the Cemetery and his wife Elizabeth was buried there in 1943. A lovely marble monument was erected in 1944 surrounded by a border of ivy. In front of the monument is the name “Lewis,” underneath a relief of a cross in a bed of flowers. The epitaph written on the back refers to Elizabeth as: “A lover of beauty and truth, She taught me how to live, And how to die.”

William Henry Lewis died at age 81 in 1949 on New Year’s Day, and his funeral was attended by Gov. Robert F. Bradford, former Boston mayor James M. Curley, and hundreds of other mourners. He was buried at Mount Auburn alongside his wife, not far from Julia Ward Howe, and in the community of colleagues and friends who shared a common devotion to the cause of equality.

William Henry Lewis is buried in Lot 6308 on Glen Avenue.

Footnotes:

[1] “Lewis’ Great Work,” AME Zion Quarterly Review 10 (October-December 1900): 63-64.

[2] “Lawyer for Negro Defends Mrs. Mohr,” New York Times, February 4, 1916. William H. Ferris, The African Abroad; or His Evolution in Western Civilization: Tracing His Development Under Caucasian Milieu. New Haven: Tuttle, Morehouse and Taylor, 1913, p. 797.