Myrtle Hart (1874-1966)

Harpist

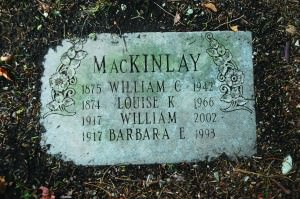

On Cuphea Path is the lot of the MacKinlay family. Behind the name on the headstone “Louise K. MacKinlay” is the story of Myrtle Hart. Hart was born in Evansville, Indiana, to Henry Hart, an accomplished violinist and composer, and Sarah Hart, a concert pianist. The family performed together throughout the Midwest and were known as “The Henry Hart Orchestra,” and also the “father-plus-five-daughters.” A headline in The Indianapolis News enthused in 1901, “Henry Hart and His Family of Musicians Always in Demand.”[1] Myrtle Hart took lessons, first with her father and then with Edmund Schuëcker, a harpist in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. She created a sensation at the British Exhibit at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition (The Chicago World’s Fair), where she was noted as a “gifted Harp Player” and the “Only Colored Woman Who Performs On This Instrument.”[2]

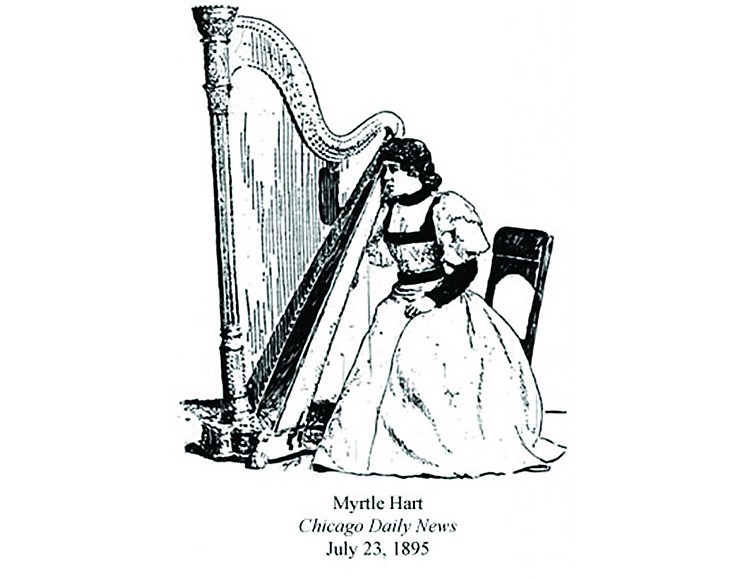

The young harpist continued playing throughout the Midwest. Her venues included summer resorts, leading theatres in Chicago, and Black churches in Chicago and Washington.[3] “I have been playing since my babyhood—almost. In fact, I can’t remember when I learned music,” Hart explained.[4] “I first played the piano, then learned the harp. I play only by inspiration. I can do nothing unless inspired.”[5] The Chicago Daily News described Hart’s virtuosity as “marked by brilliant execution, pure tones, and extreme delicacy of touch.”[6]

In 1926, Myrtle Hart married William C. MacKinlay, a widower, who lived in West Roxbury, Massachusetts and who shared her love of music. Having studied in Paris, William MacKinlay became the orchestra leader in the old City Theatre in Brockton and later, the musical director of the Colonial Theatre, a position he held for 40 years. Myrtle also played as a harpist in the Colonial Theatre.

William MacKinlay passed away at age 76 in 1942 and was buried at Mount Auburn. He may have held a special affection for the Cemetery as he had a great interest in horticulture, maintained lovely gardens, and won prizes for his entries in New England flower shows. Myrtle Hart lived another 24 years, and eventually took her place beside her husband. But the gravestone bears no inscription of the name “Myrtle Hart,” rather the name of “Louise K. MacKinlay” appears next to “William M. MacKinlay.”

In 2010, Clark Kimberling, a scholar from the University of Evansville, wrote to Mount Auburn Cemetery to share his discovery that Louise Kavanaugh MacKinlay was in fact the same person as Myrtle Hart. Kimberling had contacted Hart’s granddaughter Judith Albritton Simmons. Simmons confirmed that Hart, who was able to pass as a White person because of the color of her skin, sometimes used Louise Kavanaugh as her stage name.

“My Gran had to pass in order to play in the big symphony orchestras,” Simmons explains. “She hated this so much—the professional need for passing and the difficulties this posed for her private life.”[7] Today the Myrtle Hart Society serves to foster classically trained African American musicians and “to promote the achievements of classical musicians of color.”[8] Visitors in search of Hart’s gravesite can now find it within sight of Halcyon Lake, under the beech tree and Japanese yews—a single stone set in the ground bearing the name “Louise K. MacKinlay.”

Louise K. MacKinlay, also known as Myrtle Hart, is buried in Lot 3847 on Cuphea Path.

Footnotes:

[1] Indianapolis News, April 6, 1901

[2] “Is Gifted Harp Player,” Chicago Daily News, July 23, 1895.

[3] Indianapolis Freeman, February 13, 1915, p. 3

[4] “Is Gifted Harp Player,” 1895.

[5] “Is Gifted Harp Player,” 1895.

[6] “Is Gifted Harp Player,” 1895.

[7] Judith Albritton Simmons. “Memories of My Grandmother, Myrtle Hart.” See Professor Clark Kimberling’s webpage about Myrtle Hart.

[8] See Myrtle Hart Society website.

Top Image:

Myrtle Hart, Chicago Daily News, July 23, 1895. Myrtle Hart Society.