Hygeia Monument & Edmonia Lewis

Funerary Monument by Edmonia Lewis, one of America’s first Black Sculptors

Harriot Kezia Hunt (1805-1875) was a pioneer female physician and reformer involved in the temperance and anti-tobacco movements. Twice rejected for admission to Harvard Medical School, Hunt studied privately and developed a successful practice. In 1853, she received an honorary degree of Doctor of Medicine from the Female Medical College of Philadelphia. In 1870, Hunt commissioned a statue of Hygeia, the Greek goddess of health and hygiene, to be erected on her family lot in Mount Auburn Cemetery.

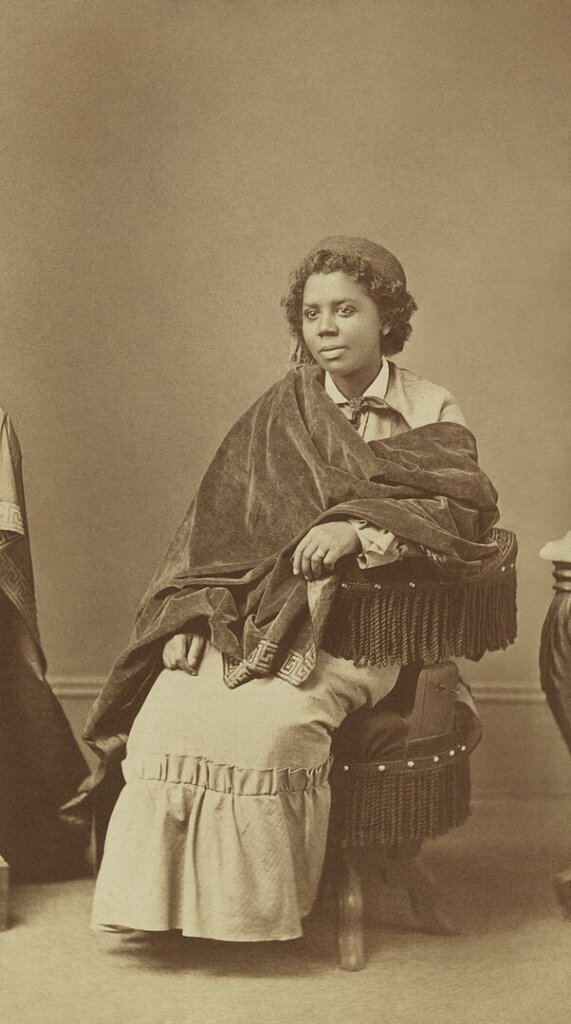

A champion of the anti-slavery and feminist movements, Hunt not surprisingly chose Edmonia Lewis (1844 – 1907) to create her memorial. Lewis’s mother was an Indigenous American, and her father was a free Black. She studied at Oberlin College, and in 1863 came to Boston, where she studied under Edward Brackett and established her own studio on Tremont Street.

One of Lewis’s most famous pieces, Forever Free, commemorates the end of the Civil War with the expressive depiction of a man and woman hearing the news that they have been emancipated. Lewis earned a reputation for her likenesses of anti-slavery leaders including John Brown, William Lloyd Garrison, and an African American hero of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, Sgt. William H. Carney. She created a portrait bust of Robert Gould Shaw, Commander of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, and sold reproductions of her bust of the celebrated hero.

Lewis felt uneasy about the recognition of her talent solely because she was a Black woman. “Some praise me because I am a colored girl, and I don’t want that kind of praise,” she told the abolitionist Lydia Maria Child.[1] Scholar Kirsten Pai Buick explains that “Lewis was not objecting to the coverage she received in the abolitionist press, nor did she ever turn down monetary aid. Rather, what she found insupportable was the condescension regarding her skill as an artist.”[2]

Lewis’s success enabled her to save enough money to move to Rome, a center for artists and writers. There she received acclaim for her talent, including from Pope Pius IX, who came to her studio and blessed her work. To this day there is still speculation about Lewis's romantic life. As a deeply private individual, not much evidence of her suspected same-sex attraction exists. Lewis never married, had no children, and spent much of her life in an artistic community of lesbian sculptors, actors, and writers.

Hygeia was erected on Hunt’s family lot in 1872, three years before Hunt’s death in 1875. The goddess carries a shawl that drapes around her right shoulder onto her back. A coiled serpent surrounds her feet. The fingers of her right hand and her facial features are now almost completely eroded, yet the grace and naturalism of the statue are still visible.

As the neoclassical style began to fall out of favor, Lewis’s career suffered a decline, and until a recent resurgence of interest in her life and work, many of her sculptures were forgotten or lost. She lived her last years in London. Both single and self-supporting, Hunt and Lewis understood the difficulties of working in male-dominated professions. How fortunate that Hunt commissioned Lewis to sculpt the neoclassical statue. Historian Marilyn Richardson reflects, “The doctor and the sculptor chose to introduce a woman of ancient power and authority into Mount Auburn Cemetery’s landscapes of influence, a woman who, in a place of loss and bereavement, they posed striding forth with the attributes of wisdom and well-being.”[3] The ethereal figure stands among the most cherished monuments at Mount Auburn, representing the work of one of the only African American women to achieve professional recognition for her contributions to nineteenth-century art.

Footnotes:

[1] Interview with Lydia Maria Child. Liberator, February 19, 1864, n.p. in Kirsten Pai Buick, Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010, p. 13.

[2] Kirsten Pai Buick, Child of the Fire: Mary Edmonia Lewis and the Problem of Art History’s Black and Indian Subject. Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2010, p. 13.

[3] Correspondence with Marilyn Richardson, January 15, 2013.