Adina E. White (1861?-1930)

Artist, Businesswoman, & Local Philanthropist

Forgotten until renewed interest in Gertrude Wright Morgan led to her rediscovery, Adina E. White was once a well-known figure in Cambridge. An intellectual, an artist, a businesswoman, and a supporter of local charities, she led an unusual life, and we can only regret that, at least so far, we have so little of her story in her own voice.

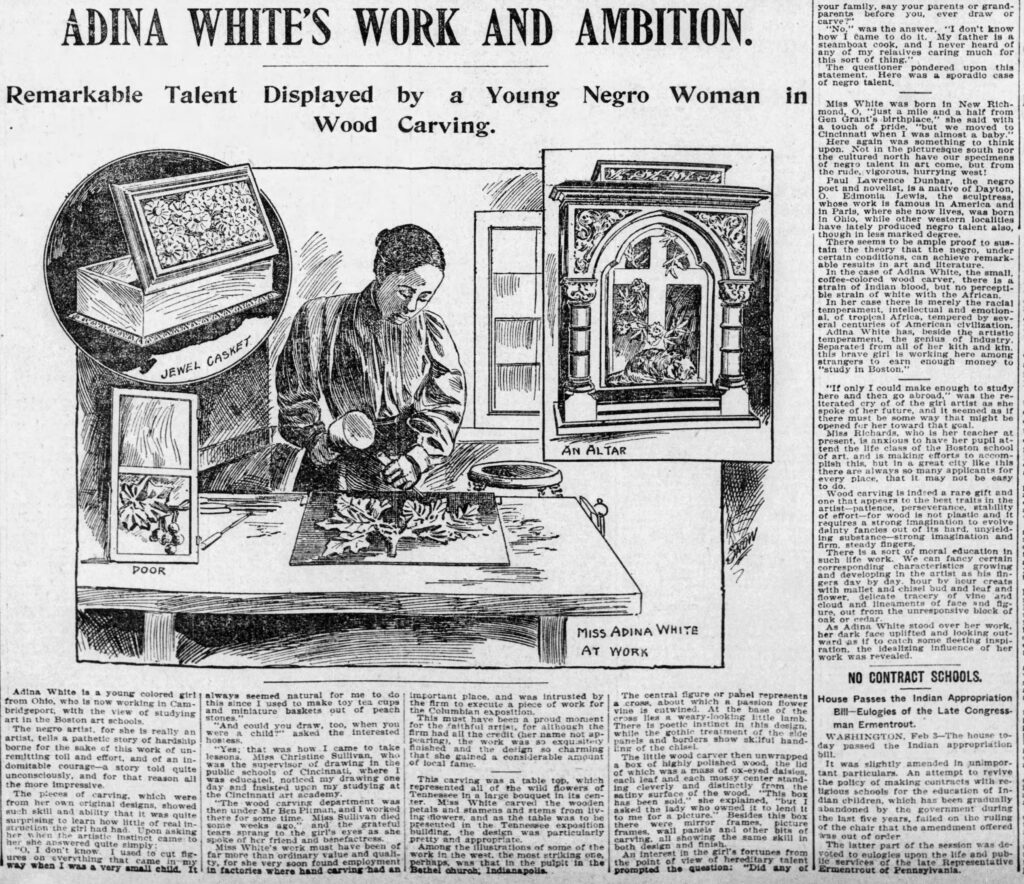

Writing about “Cambridge’s Colored Citizens” in the Cambridge Chronicle in 1946, local attorney and Boston NAACP president Ray Guild conjured up bygone days: “One unforgettable sight was that of our newsboy Mrs. Adina White, running, as she made her delivery route of newspapers.” White had died in 1930, and by the 1940s, it’s likely few people knew that her artwork had been shown at the Columbian Exposition, or that she had once been an editor of Ringwood’s Afro-American Journal of Fashion, or that famed novelist and editor Pauline E. Hopkins had written about her in both the Boston Globe and in her groundbreaking series in The Colored American Magazine, “Famous Women of the Negro Race.”

Adina White was born, probably in 1861, to Georgianna Walker White and Thomas D. White, a steamboat cook, in New Richmond, OH, a town on the Ohio River home to an active abolitionist community. Thomas and Georgianna had both been born in Kentucky; both were free before the Civil War, as were the parents of both. Indeed, Georgianna’s father, James G. Walker, was documented as free in Georgetown, KY, in 1830. White told Hopkins that she had started carving peach stones as a small child and had also enjoyed drawing.

Sometime between 1870 and 1880, White’s parents moved their family along the river to Cincinnati. In the segregated public schools there, White came to the attention of the supervisor of drawing, who pushed her to enter the Cincinnati Art Academy. She studied woodcarving under Benn Pitman, a polymath Englishman who believed that carving and other decorative arts could afford new professions for women. One reference has her as a Pitman student in 1874–75 at the School of Design (when she would have been a young teenager) and from 1884 to 1888 at the Art Institute. In 1876, Pitman and his students sent a large collection of work to the Women’s Pavilion at the Philadelphia International Exhibition, including a dressing bureau and a large picture frame carved by White.

It seems likely that by the late 1880s, White was supporting herself at least in part by her carving. In 1888, the Cincinnati Enquirer noted that she had sold a carved frame that had been exhibited at the Cincinnati Centennial Exposition for $75, a considerable amount, to “an art connoisseur.” By the early 1890s, she was listing herself in the Cincinnati Directory as a woodcarver, the only known African-American woman so listed. We know from Hopkins’s article and other sources that acclaim had come her way for a number of her pieces. A factory that employed her had her make a tabletop that included a carved bouquet of Tennessee wildflowers; this piece was displayed in the Tennessee Exposition Building at the 1893 Columbian Exposition and “was so exquisitely finished and the design so charming that she gained great local fame.” Among her projects, she was commissioned to carve the pulpit for the Bethel AME Church in Indianapolis, a gift from the minister to his wife. Perhaps her “great local fame” brought her to the attention of Julia Ringwood Coston, who made her editor of the art section of Ringwood’s Afro-American Journal of Fashion, a pioneering periodical published in Cleveland and distributed throughout the United States and in the Caribbean.

White had other interests, as well. The Enquirer reported monthly meetings of the Whittier Club (undoubtedly named for the abolitionist poet), hosted by White at her home. It appears the club’s focus was literature: at one meeting they read and discussed Bret Harte’s works; at another, they were to hear a paper read on “Negro Lore.” Other members of this club indicate White’s social network. One, Dr. Consuelo Clark, the daughter of Peter H. Clark, founder and principal of Ohio’s first public high school for Black students and remembered as the first African-American socialist in the United States, had also attended the Art Academy and then gone on to graduate from Boston University medical school and to be the first African-American woman licensed to practice medicine in Ohio.

In 1895, White shows up in the St. Louis, MO, city directory as a teacher, which gives us our first clue to her connection to Gertrude Wright Morgan. White taught drawing at St. Louis’s Sumner High School, which had been established in 1875 as the first high school for Black students west of the Mississippi. She most likely got this position through her connection to Peter H. Clark; he had lost his principalship in Cincinnati for political reasons in 1886 and was hired as a teacher at Sumner in 1888. Gertrude Wright had been teaching at Sumner since at least the late 1870s. (She probably met her future husband, Clement G. Morgan, there, as he also taught at Sumner before heading east to enroll at Boston Latin and then Harvard.) In 1895 White and Wright even lived in the same rooming house, owned by a Black woman teacher who rented rooms to a number of other Black women teachers.

In 1897, both White and Wright resigned from Sumner High. Wright married Morgan and headed with him to Cambridge. White apparently returned to Cincinnati, where she again listed herself in the city directory as a woodcarver. But Cincinnati, including its formerly famous reputation for art carving, was now in decline. White, too, moved to Cambridge. She told Pauline Hopkins that she had started attending art schools in Boston in 1900.

In the 1900 Cambridge census, White is listed as a woodcarver lodging with the Johnson family on Worcester St. It’s probable, however, that woodcarving couldn’t provide her with an adequate living. By 1903, she had turned her substantial energies to business, opening a newsdealer shop at 402 Massachusetts Avenue, where the Salvation Army is now. By the time the 1910 Cambridge census was taken, White had brought her widowed mother, Georgianna, to live with her as lodgers with the Augustine family at 289 Washington St. In 1913, 75-year-old Georgianna died of pneumonia at the home she shared with White at 476 Mass Ave.

Through at least 1925, White operated a combination of newsdealer, employment office, and florist businesses at various storefronts on Mass Ave between Windsor and Main streets. As Ray Guild wrote, she also ran up and down the streets delivering papers during these years. In 1927, at the age of about 65, she bought a house at 8 Village Street. In 1929, Clement Morgan died and, soon after, Gertrude Wright Morgan moved into this house with her old friend White, another adult woman boarder, and four children White was fostering.

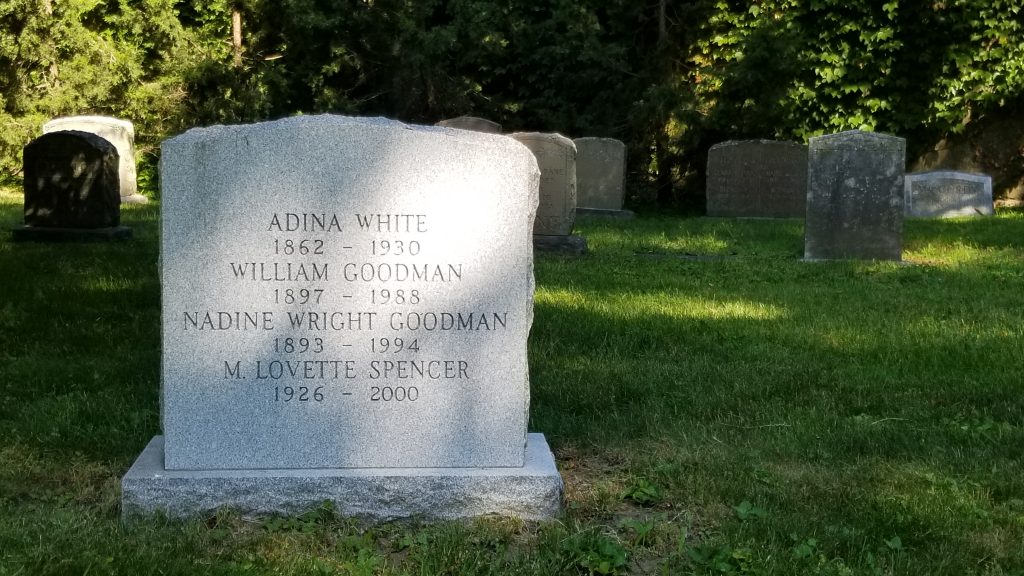

But in December 1930, White died. In her will, she left $100 each to a sister-in-law and a cousin and to the Union Baptist Church and Colored Orphan Asylum back in Cincinnati. Since moving to Cambridge, she had donated money to various local charities and fund drives. Guild wrote that “her charities were many; and when she passed away, both the nuns and Rev. A. Butler, of St. Mary’s church, insisted on having a full requiem mass over her remains. Nadine Wright, niece of Clement Morgan,…had her buried in her family’s lot at Mount Auburn Cemetery.” In 1931, Wright Morgan died, and the two great friends and extraordinary women were reunited once again.

This Biographical Portrait was prepared by Leslie Brunetta, 2020

Footnotes:

1850 United States Census, Clermont County, Ohio, digital image s.v. “Jackson White,” Ancestry.com.

1850 United States Census, Clermont County, Ohio, digital image s.v. “James G. Walker,” Ancestry.com.

1860 United States Census, New Richmond, Clermont County, Ohio, digital image s.v. “Thomas White,” Ancestry.com.

1870 United States Census, New Richmond, Clermont County, Ohio, digital image s.v. “Thomas White,” Ancestry.com.

1880 United States Census, Cincinnati, Ohio, digital image s.v. “D. Thomas White,” Ancestry.com.

1900 United States Census, Cambridge, Massachusetts, digital image s.v. “William Johnson,” Ancestry.com.

1910 United States Census, Cambridge, Massachusetts, digital image s.v. “Joseph D. Augustine,” Ancestry.com.

1930 United States Census, Cambridge, Massachusetts, digital image s.v. “Adina E. White,” Ancestry.com.

Commonwealth of Massachusetts Standard Certificate of Death for Georgianna White, 1913, digital image, Ancestry.com.

Cambridge Chronicle. 1931. “Court House News,” January 16, sec. B, p. 4.

Cambridge Directory. Various dates. Boston: W.A. Greenough & Co.

Cincinnati Enquirer. 1888. “Items on the Wing,” November 3, p. 16.

Cincinnati Enquirer. 1889a. “Items on the Wing,” February 9, p. 16.

Cincinnati Enquirer. 1889b. “Items on the Wing,” March 23, p. 16.

Cincinnati Enquirer. 1889c. “Items on the Wing,” May 18, p. 16.

Gould’s St. Louis Directory. Various dates. St. Louis, MO: Gould Directory Co.

Guild, Ray. 1946. “Cambridge’s Colored Citizens.” Cambridge Chronicle, December 12, pp. 16, 23.[Hopkins, Pauline E.] 1900. “Adina White’s Work and Ambition.” Boston Globe, February 4, p. 24.

Hopkins, Pauline E. 1902. “Famous Women of the Negro Race: X: Artists.” The Colored American Magazine, September, pp. 362–367. http://coloredamerican.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/CAM_5.5_1902.09.NS_.pdf.

Howe, Jennifer L., ed. 2003. Cincinnati Art Carved Furniture and Interiors. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press.

St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat. 1897. “Free School Books,” September 15, p. 9.

Topeka Daily Capital. 1892. “Afro-Americans,” September 9, p. 5.

Williams’ Cincinnati Directory. Various dates. Cincinnati: Williams & Co.

Woodson, Carter G. 1925. Free Negro Heads of Families in the United States in 1830, Together with a Brief Treatment of the Free Negro. Washington, DC: The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History.