Joseph Story’s Consecration Address

MY FRIENDS, —

The occasion which brings us together, has much in it calculated to awaken our sensibilities, and cast a solemnity over our thoughts. We are met to consecrate these grounds exclusively to the service and repose of the dead.

The duty is not new; for it has been performed for countless millions. The scenery is not new; for the hill and the valley, the still, silent dell, and the deep forest, have often been devoted to the same pious purpose. But that, which must always give it a peculiar interest, is, that it can rarely occur except at distant intervals ; and, whenever it does, it must address itself to feelings intelligible to all nations, and common to all hearts.

The patriarchal language of four thousand years ago is precisely that, to which we would now give utterance. We are “strangers and sojourners” here. We have need of “a possession of a burying-place, that we may bury our dead out of our sight.” Let us have the field, and the cave which is therein ; and all the trees, that are in the field, and that are in the borders round about ; ” and let them “be made sure for a possession of a burying-place.”

It is the duty of the living thus to provide for the dead. It is not a mere office of pious regard for others; but it comes home to our own bosoms, as those who are soon to enter upon the common inheritance.

If there are any feelings of our nature, not bounded by earth, and yet stopping short of the skies, which are more strong and more universal than all others, they will be found in our solicitude as to the time and place and manner of our death ; in the desire to die in the arms of our friends ; to have the last sad offices to our remains performed by their affection ; to repose in the land of our nativity ; to be gathered to the sepulchres of our fathers. It is almost impossible for us to feel, nay, even to feign, indifference on such a subject.

Poetry has told us this truth in lines of transcendent beauty and force, which find a response in every breast : —

“For who, to dumb Forgetfulness a prey,

This pleasing, anxious being e’er resigned,

Left the warm precincts of the cheerful day,

Nor cast one longing, lingering look behind ?

On some fond breast the parting soul relies;

Some pious drops the closing eye requires;

E’en from the tomb the voice of Nature cries;

E’en in our ashes live their wonted fires.”

It is in vain, that Philosophy has informed us, that the whole earth is but a point in the eyes of its Creator, –nay, of his own creation; that, wherever we are,– abroad or at home, –on the restless ocean, or the solid land, –we are still under the protection of his providence, and safe, as it were, in the hollow of his band. It is in vain that Religion has instructed us, that we are but dust, and to dust we shall return, –that whether our remains are scattered to the corners of the earth, or gathered in sacred urns, there is a sure and certain hope of a resurrection of the body and a life everlasting. These truths, sublime and glorious as they are, leave untouched the feelings, of which I have spoken, or, rather, they impart to them a more enduring reality. Dust as we are, the frail tenements, which enclose our spirits but for a season, are dear, are inexpressibly dear to us. We derive solace, nay, pleasure from the reflection, that when the hour of separation comes, these earthly remains will still retain the tender regard of those whom we leave behind; — that the spot, where they shall lie, will be remembered with a fond and soothing reverence; –that our children will visit it in the midst of their sorrows ; and our kindred in remote generations feel that a local inspiration hovers round it.

Let him speak, who has been on a pilgrimage of health to a foreign land. Let him speak, who has watched at the couch of a dying friend, far from his chosen home. Let him speak, who has committed to the bosom of the deep, with a sudden, startling plunge, the narrow shroud of some relative or companion. Let such speak, and they will tell you, that there is nothing which wrings the heart of the dying, –ay, and of the surviving,– with sharper agony, than the thought, that they are to sleep their last sleep in the land of strangers, or in the unseen depths of the ocean.

“Bury me not, I pray thee,” said the patriarch Jacob, “bury me not in Egypt: but I will lie with my fathers. And thou shalt carry me out of Egypt; and bury me in their burying place.” — “There they buried Abraham and Sarah his wife; there they buried Isaac and Rebecca his wife; and there I buried Leah.”

Such are the natural expressions of human feeling, as they fall from the lips of the dying. Such are the reminiscences, that forever crowd on the confines of the passes to the grave. We seek again to have our home there with our friends, and to be blest by a communion with them. It is a matter of instinct, not of reasoning. It is a spiritual impulse, which supersedes belief, and disdains question. But it is not chiefly in regard to the feelings belonging to our own mortality, however sacred and natural, that we should contemplate the establishment of repositories of this sort. There are higher moral purposes, and more affecting considerations, which belong to the subject. We should accustom ourselves to view them rather as means, than as ends; rather as influences to govern human conduct, and to moderate human suffering, than as cares incident to a selfish foresight.

It is to the living mourner — to the parent, weeping over his dear dead child –to the husband, dwelling in his own solitary desolation — to the widow, whose heart is broken by untimely sorrow — to the friend, who misses at every turn the presence of some kindred spirit: — it is to these, that the repositories of the dead bring home thoughts full of admonition, of instruction, and, slowly but surely, of consolation also. They admonish us, by their very silence, of our own frail and transitory being. They instruct us in the true value of life, and in its noble purposes, its duties, and its destination. They spread around us, in the reminiscences of the past, sources of pleasing, though melancholy reflection.

We dwell with pious fondness on the characters and virtues of the departed; and, as time interposes its growing distances between us and them, we gather up, with more solicitude, the broken fragments of memory, and weave, as it were, into our very hearts, the threads of their history. As we sit down by their graves, we seem to hear the tones of their affection, whispering in our ears. We listen to the voice of their wisdom, speaking in the depths of our souls. We shed our tears; but they are no longer the burning tears of agony. They relieve our drooping spirits, and come no longer over us with a deathly faintness. We return to the world, and we feel ourselves purer, and better, and wiser, from this communion with the dead.

I have spoken but of feelings and associations common to all ages, and all generations of men — to the rude and the polished — to the barbarian and the civilized — to the bond and the free — to the inhabitant of the dreary forests of the north, and the sultry regions of the south — to the worshipper of the sun, and the worshipper of idols — to the Heathen, dwelling in the darkness of his cold mythology, and to the Christian, rejoicing in the light of the true God. Everywhere we trace them in the characteristic remains of the most distant ages and nations, and as far back as human history carries its traditionary outlines. They are found in the barrows, and cairns, and mounds of olden times, reared by the uninstructed affection of savage tribes; and, everywhere, the spots seem to have been selected with the same tender regard to the living and the dead ; that the magnificence of nature might administer comfort to human sorrow, and incite human sympathy.

The aboriginal Germans buried their dead in groves consecrated by their priests. The Egyptians gratified their pride and soothed their grief by interring them in their Elysian fields, or embalming them in their vast catacombs, or enclosing them in their stupendous pyramids, the wonder of all succeeding ages. The Hebrews watched with religious care over their places of burial. They selected, for this purpose, ornamented gardens and deep forests, and fertile valleys, and lofty mountains ; and they still designate them with a sad emphasis, as the “House of the Living.” The ancient Asiatics lined the approaches to their cities with sculptured sarcophagi, and mausoleums, and other ornaments, embowered in shrubbery, traces of which may be seen among their magnificent ruins. The Greeks exhausted the resources of their exquisite art in adorning the habitations of the dead. They discouraged interments within the limits of their cities ; and consigned their relics to shady groves, in the neighborhood of murmuring streams and mossy fountains, close by the favorite resorts of those who were engaged in the study of philosophy and nature, and called them, with the elegant expressiveness of their own beautiful language, CEMETERIES,* or “ Places of Repose. ” [* Xoίμητηgία — literally, places of sleep]. The Romans, faithful to the example of Greece, erected the monuments to the dead in the suburbs of the eternal city, (as they proudly denominated it,) on the sides of their spacious roads, in the midst of trees and ornamented walks, and ever-varying flowers. The Appian Way was crowded with columns, and obelisks, and cenotaphs to the memory of her heroes and sages ; and, at every turn, the short but touching inscription met the eye, — Siste Viator, — Pause Traveller, –inviting at once to sympathy and thoughtfulness. Even the humblest Roman could read on the humblest gravestone the kind offering — “May the earth lie lightly on these remains!” “Sit tibi terra levis.” And the Moslem Successors of the emperors, indifferent as they may be to the ordinary exhibitions of the fine arts, place their burying-grounds in rural retreats, and embellish them with studious taste as a religious duty. The cypress is planted at the head and foot of every grave, and waves with a mournful solemnity over it. These devoted grounds possess an inviolable sanctity. The ravages of war never reach them ; and victory and defeat equally respect the limits of their domain. So that it has been remarked, with equal truth and beauty, that while the cities of the living are subject to all the desolations and vicissitudes incident to human affairs, the cities of the dead enjoy an undisturbed repose, without even the shadow of change.

But I will not dwell upon facts of this nature. They demonstrate, however, the truth, of which I have spoken. They do more ; they furnish reflections suitable for our own thoughts on the present occasion.

If this tender regard for the dead be so absolutely universal, and so deeply founded in human affection, why is it not made to exert a more profound influence on our lives ? Why do we not enlist it with more persuasive energy in the cause of human improvement ? Why do we not enlarge it as a source of religious consolation ? Why do we not make it a more efficient instrument to elevate Ambition, to stimulate Genius, and to dignify Learning ? Why do we not connect it indissolubly with associations, which charm us in Nature and engross us in Art ? Why do we not dispel from it that unlovely gloom, from which our hearts turn as from a darkness that ensnares, and a horror that appalls our thoughts?

To many, nay, to most of the heathen, the burying place was the end of all things. They indulged no hope, at least, no solid hope, of any future intercourse or reunion with their friends. The farewell at the grave was a long, and an everlasting farewell. At the moment, when they breathed it, it brought to their hearts a startling sense of their own wretchedness. Yet, when the first tumults of anguish were passed, they visited the spot, and strewed flowers, and garlands, and crowns around it, to assuage their grief, and nourish their piety. They delighted to make it the abode of the varying beauties of Nature ; to give it attractions, which should invite the busy and the thoughtful; and yet, at the same time, afford ample scope for the secret indulgence of sorrow.

Why should not Christians imitate such examples ? They have far nobler motives to cultivate moral sentiments and sensibilities; to make cheerful the pathways to the grave; to combine with deep meditations on human mortality the sublime consolations of religion. We know, indeed, as they did of old, that “man goeth to his long home, and the mourners go about the streets.” But that home is not an everlasting home ; and the mourners may not weep as those who are without hope. What is the grave to Us, but a thin barrier dividing Time from Eternity, and Earth from Heaven? What is it but “ the appointed place of rendezvous, where all the travellers on life’s journey meet ” for a single night of repose ?

“ ‘Tis but a night –a long and moonless night,

We make the Grave our Bed, and then are gone.”

Know we not

—— “ The time draws on

When not a single spot of burial earth,

Whether on land, or in the spacious sea,

But must give up its long committed dust

Inviolate ? ” —

Why then should we darken with systematic caution all the avenues to these repositories? Why should we deposit the remains of our friends in loathsome vaults, or beneath the gloomy crypts and cells of our churches, where the human foot is never heard, save when the sickly taper lights some new guest to his appointed apartment, and “ lets fall a supernumerary horror ” on the passing procession ? Why should we measure out a narrow portion of earth for our graveyards in the midst of our cities, and heap the dead upon each other with a cold, calculating parsimony, disturbing their ashes, and wounding the sensibilities of the living ? Why should we expose our burying grounds to the broad glare of day, to the unfeeling gaze of the idler, to the noisy press of business, to the discordant shouts of merriment, or to the baleful visitations of the dissolute ? Why should we bar up their approaches against real mourners, whose delicacy would shrink from observation, but whose tenderness would be soothed by secret visits to the grave, and holding converse there with their departed joys ? Why all this unnatural restraint upon our sympathies and sorrows, which confines the visit to the grave to the only time, in which it must be utterly useless —when the heart is bleeding with fresh anguish, and is too weak to feel, and too desolate to desire consolation ?

It is painful to reflect, that the Cemeteries in our cities, crowded on all sides by the overhanging habitations of the living, are walled in only to preserve them from violation. And that in our country towns they are left in a sad, neglected state, exposed to every sort of intrusion, with scarcely a tree to shelter their barrenness, or a shrub to spread a grateful shade over the newmade hillock.

These things were not always so among Christians. They are not worthy of us. They are not worthy of Christianity in our day. There is much in these things, that casts a just reproach upon us in the past. There is much that demands for the future a more spiritual discharge of our duties.

Our Cemeteries rightly selected, and properly arranged, may be made subservient to some of the highest purposes of religion and human duty. They may preach lessons, to which none may refuse to listen, and which all, that live, must hear. Truths may be there felt and taught in the silence of our own meditations, more persuasive, and more enduring, than ever flowed from human lips. The grave hath a voice of eloquence, nay, of superhuman eloquence, which speaks at once to the thoughtlessness of the rash, and the devotion of the good ; which addresses all times, and all acres, and all sexes ; which tells of wisdom to the wise, and of comfort to the afflicted ; which warns us of our follies and our dangers ; which whispers to us in accents of peace, and alarms us in tones of terror; which steals with a healing balm into the stricken heart, and lifts up and supports the broken spirit; which awakens a new enthusiasm for virtue, and disciplines us for its severer trials and duties ; which calls up the images of the illustrious dead, with an animating presence for our example and glory; and which demands of us, as men, as patriots, as Christians, as immortals, that the powers given by God should be devoted to his, service, and the minds created by his love, should return to him with larger capacities for virtuous enjoyment, and with more spiritual and intellectual brightness.

It should not be for the poor purpose of gratifying our vanity or pride, that we should erect columns, and obelisks, and monuments, to the dead ; but that we may read thereon much of our own destiny and duty. We know, that man is the creature of associations and excitements. Experience may instruct, but habit, and appetite, and passion, and imagination, will exercise a strong dominion over him. These are the Fates, which weave the thread of his character, and unravel the mysteries of his conduct. The truth, which strikes home, must not only have the approbation of his reason, but it must be embodied in a visible, tangible, practical form. It must be felt, as well as seen. It must warm, as well as convince.

It was a saying of Themistocles, that the trophies of Miltiades would not suffer him to sleep. The feeling, thus expressed, has a deep foundation in the human mind; and, as it is well or ill directed, it will cover us with shame, or exalt us to glory. The deeds of the great attract but a cold and listless admiration, when they pass in historical order before us like moving shadows. It is the trophy and the monument, which invest them with a substance of local reality. Who, that has stood by the tomb of Washington on the quiet Potomac, has not felt his heart more pure, his wishes more aspiring, his gratitude more warm, and his love of country touched by a holier flame? Who, that should see erected in shades, like these, even a cenotaph to the memory of a man, like Buckminster, that prodigy of early genius, would not feel, that there is an excellence over which death hath no power, but which lives on through all time, still freshening with the lapse of ages.

But passing from those, who by their talents and virtues have shed lustre on the annals of mankind, to cases of mere private bereavement, who, that should deposit in shades, like these, the remains of a beloved friend, would not feel a secret pleasure in the thought, that the simple inscription to his worth would receive the passing tribute of a sigh from thousands of kindred hearts ? That the stranger and the traveller would linger on the spot with a feeling of reverence ? That they, the very mourners themselves, when they should revisit it, would find there the verdant sod, and the fragrant flower, and the breezy shade ? That they might there, unseen, except of God, offer up their prayers, or indulge the luxury of grief? That they might there realize, in its full force, the affecting beatitude of the Scriptures : “ Blessed are they that mourn, for they shall be comforted ? ”

Surely, surely, we have not done all our duty, if there yet remains a single incentive to human virtue, without its due play in the action of life, or a single stream of happiness, which has not been made to flow in upon the waters of affliction.

Considerations, like those, which have been suggested, have for a long time turned the thoughts of many distinguished citizens to the importance of some more appropriate places of sepulture. There is a growing sense in the community of the inconveniences, and painful associations, not to speak of the unhealthiness of interments, beneath our churches. The tide, which is flowing with such a steady and widening current into the narrow peninsula of our Metropolis, not only forbids the enlargement of the common limits, but admonishes us of the increasing dangers to the ashes of the dead from its disturbing movements. Already in other cities, the churchyards are closing against the admission of new incumbents, and begin to exhibit the sad spectacle of promiscuous ruins and intermingled graves.

We are, therefore, but anticipating at the present moment, the desires, nay, the necessities of the next generation. We are but exercising a decent anxiety to secure an inviolable home for ourselves and our posterity. We are but invitingour children and their descendants, to what the Moravian Brothers have, with such exquisite propriety, designated as “the Field of Peace.”

A rural Cemetery seems to combine in itself all the advantages, which can be proposed to gratify human feelings, or tranquillize human fears; to secure the best religious influences, and to cherish all those associations which cast a cheerful light over the darkness of the grave.

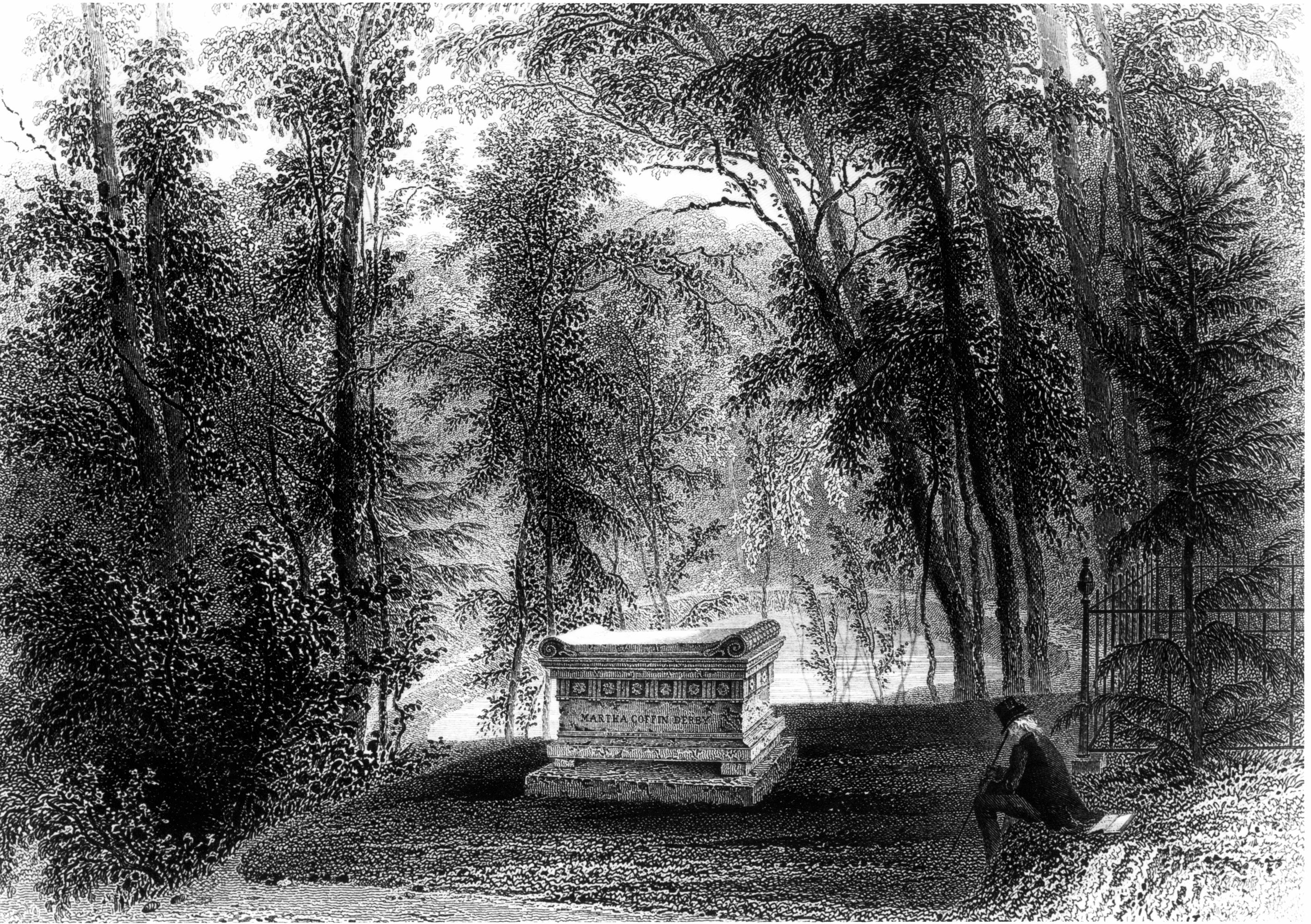

And what spot can be more appropriate than this, for such a purpose? Nature seems to point it out with significant energy, as the favorite retirement for the dead. There are around us all the varied features of her beauty and grandeur— the forest-crowned height ; the abrupt acclivity ; the sheltered valley ; the deep glen ; the grassy glade ; and the silent grove. Here are the lofty oak, the beech, that “ wreaths its old fantastic roots so high, ” the rustling pine, and the drooping willow ; — the tree, that sheds its pale leaves every autumn, a fit emblem of our own transitory bloom ; and the evergreen, with its perennial shoots, instructing us, that “ the wintry blast of death kills not the buds of virtue. ” Here is the thick shrubbery to protect and conceal the new-made grave ; and there is the wild-flower creeping along the narrow path, and planting its seeds in the upturned earth. All around us there breathes a solemn calm, as if we were in the bosom of a wilderness, broken only by the breeze as it murmurs through the tops of the forest, or by the notes of the warbler pouring forth his matin or his evening song.

Ascend but a few steps, and what a change of scenery to surprise and delight us. We seem, as it were in an instant, to pass from the confines of death, to the bright and balmy regions of life. Below us flows the winding Charles with its rippling current, like the stream of time hastening to the ocean of eternity. In the distance, the City, –at once the object of our admiration and our love, –rears its proud eminences, its glittering spires, its lofty towers, its graceful mansions, its curling smoke, its crowded haunts of business and pleasure, which speak to the eye, and yet leave a noiseless loneliness on the ear. Again we turn, and the walls of our venerable University rise before us, with many a recollection of happy days passed there in the interchange of study and friendship, and many a grateful thought of the affluence of its learning, which has adorned and nourished the literature of our country. Again we turn, and the cultivated farm, the neat cottage, the village church, the sparkling lake, the rich valley, and the distant hills, are before us through opening vistas ; and we breathe amidst the fresh and varied labors of man.

There is, therefore, within our reach, every variety of natural and artificial scenery, which is fitted to awaken emotions of the highest and most affecting character. We stand, as it were, upon the borders of two worlds; and as the mood of our minds may be, we may gather lessons of profound wisdom by contrasting the one with the other, or indulge in the dreams of hope and ambition, or solace our hearts by melancholy meditations.

Who is there, that in the contemplation of such a scene, is not ready to exclaim with the enthusiasm of the Poet,

“Mine be the breezy hill that skirts the down,

Where a green, grassy turf is all I crave,

With here and there a violet bestrown,

Fast by a brook, or fountain’s murmuring wave,

And many an evening’s sun shine sweetly on my grave ? ”

And we are met here to consecrate this spot, by these solemn ceremonies, to such a purpose. The Legislature of this Commonwealth, with a parental foresight, has clothed the Horticultural Society with authority (if I may use its own language) to make a perpetual dedication of it, as a Rural Cemetery or Burying-Ground, and to plant and embellish it with shrubbery, and flowers, and trees, and walks, and other rural ornaments. And I stand here by the order and in behalf of this Society, to declare that, by these services, it is to be deemed henceforth and forever so dedicated. Mount Auburn, in the noblest sense, belongs no longer to the living, but to the dead. It is a sacred, it is an eternal trust. It is consecrated ground. May it remain forever inviolate !

What a multitude of thoughts crowd upon the mind in the contemplation of such a scene. How much of the future, even in its far distant reaches, rises before us with all its persuasive realities. Take but one little narrow space of time, and how affecting are its associations ! Within the flight of one half century, how many of the great, the good, and the wise, will be gathered here! How many in the loveliness of infancy, the beauty of youth, the vigor of manhood, and the maturity of age, will lie down here, and dwell in the bosom of their mother earth! The rich and the poor, the gay and the wretched, the favorites of thousands, and the forsaken of the world, the stranger in his solitary grave, and the patriarch surrounded by the kindred of a long lineage! How many will here bury their brightest hopes, or blasted expectations ! How many bitter tears will here be shed! How many agonizing sighs will here be heaved! How many trembling feet will cross the pathways, and returning, leave behind them the dearest objects of their reverence or their love !

And if this were all, sad indeed, and funereal would be our thoughts ; gloomy, indeed, would be these shades, and desolate these prospects. But — thanks be to God — the evils, which he permits, have their attendant mercies, and are blessings in disguise. The bruised reed will not be laid utterly prostrate. The wounded heart will not always bleed. The voice of consolation will spring up in the midst of the silence of these regions of death. The mourner will revisit these shades with a secret, though melancholy pleasure. The band of friendship will delight to cherish the flowers, and the shrubs, that fringe the lowly grave, or the sculptured monument. The earliest beams of the morning will play upon these summits with a refreshing cheerfulness; and the lingering tints of evening hover on them with a tranquilizing glow. Spring will invite thither the footsteps of the young by its opening foliage ; and Autumn detain the contemplative by its latest bloom. The votary of learning and science will here learn to elevate his genius by the holiest of studies. The devout will here offer up the silent tribute of pity, or the prayer of gratitude. The rivalries of the world will here drop from the heart ; the spirit of forgiveness will gather new impulses; the selfishness of avarice will be checked ; the restlessness of ambition will be rebuked; vanity will let fall its plumes; and pride, as it sees “ what shadows we are, and what shadows we pursue, ” will acknowledge the value of virtue as far, immeasurably far, beyond that of fame.

But that, which will be ever present, pervading these shades, like the noonday sun, and shedding cheerfulness around, is the consciousness, the irrepressible consciousness, amidst all these lessons of human mortality, of the higher truth, that we are beings, not of time but of eternity — “ That this corruptible must put on incorruption, and this mortal must put on immortality. ” That this is but the threshold and starting point of an existence, compared with whose duration the ocean is but as a drop, nay, the whole creation an evanescent quantity.

Let us banish, then, the thought, that this is to be the abode of a gloom, which will haunt the imagination by its terrors, or chill the heart by its solitude. Let us cultivate feelings and sentiments more worthy of ourselves, and more worthy of Christianity. Here let us erect the memorials of our love, and our gratitude, and our glory. Here let the brave repose, who have died in the cause of their country. Here let the statesman rest, who has achieved the victories of peace, not less renowned than war. Here let genius find a home, that has sung immortal strains, or has instructed with still diviner eloquence. Here let learning and science, the votaries of inventive art, and the teacher of the philosophy of nature come. Here let youth and beauty, blighted by premature decay, drop, like tender blossoms, into the virgin earth; and here let age retire, ripened for the harvest. Above all, here let the benefactors of mankind, the good, the merciful, the meek, the pure in heart, be congregated; for to them belongs an undying praise.

And let us take comfort, nay, let us rejoice, that in future ages, long after we are gathered to the generations of other days, thousands of kindling hearts will here repeat the sublime declaration, “ Blessed are the dead, that die in the Lord, for they rest from their labors; and their works do follow them. ”