Benjamin Franklin Roberts (1814-1887)

Publisher, Editor, and Abolitionist

Born a free man, Benjamin Roberts was a son of Robert Roberts, a servant to families on Beacon Hill, and author of one of the first successful books on household management. His mother was Sarah Easton Roberts, the daughter of James Easton, a Revolutionary War soldier. In his early twenties, Benjamin Roberts received training as a shoemaker. He later started a printing office where he produced pamphlets, reports, and other literature for Black and abolitionist groups. His operation also served as a training ground for African American youth to gain experience in the printing business.

Roberts published one of the early African American newspapers, The Anti-Slavery Herald. While it did not survive long against the popularity of papers like The Liberator, Roberts noted that it was the first paper published, printed, and edited by an African American in the country. In The Self Elevator, a second anti-slavery newspaper edited by Roberts, he asserted that through the skilled trades, Blacks could “command respect of all good citizens.”[1]

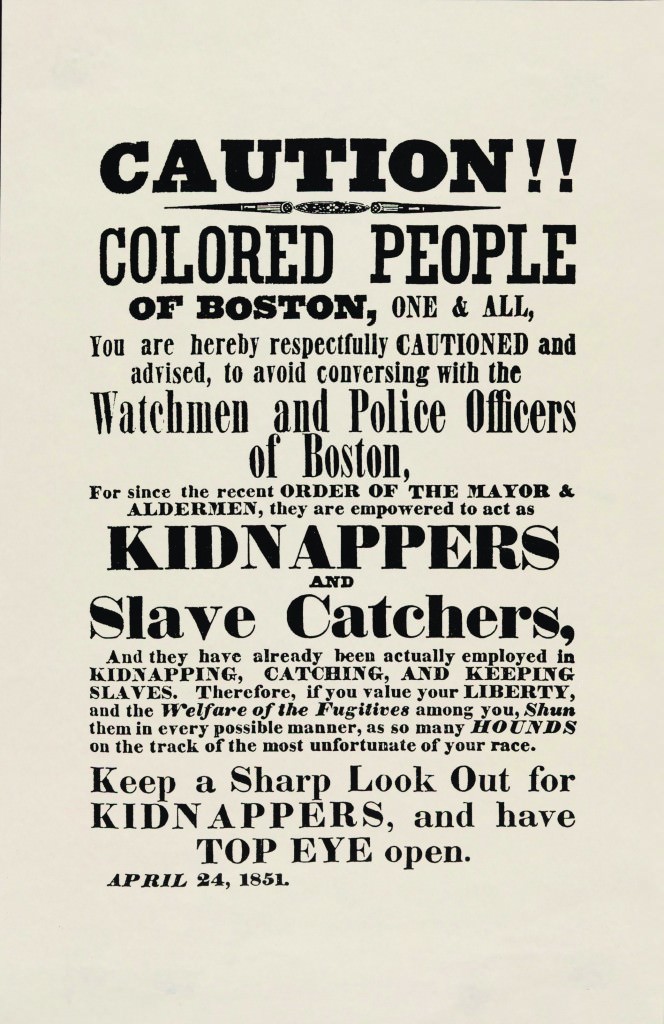

In 1850, Roberts’s Report of the Colored People of the City of Boston, on the Subject of Exclusive Schools focused on the case he had filed on behalf of his five-year-old daughter, Sarah.[2] Roberts advocated for Sarah Roberts’s right to attend one of the several White schools in her neighborhood that she walked past every day on her route to the Smith School for Black children.[3] Roberts remembered the sting of his own experience as a young student passing by other White students: “We were looked upon, by them, as unworthy to be instructed in common with others.”[4]

To argue the case, Roberts hired Robert Morris, one of the first Black lawyers in the United States, and Charles Sumner, the lawyer, reformer, and future senator. Sumner eloquently spoke to the human and moral costs to all in the case of Sarah C. Roberts v. The City of Boston. He asserted that “The whites themselves are injured by the separation. . . . they are taught to regard a portion of the human family . . . as a separate and degraded class; they are taught practically to deny . . . the Brotherhood of Man.”[5] The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Chief Justice Lemuel Shaw, who did not believe the courts had a place in reforming social prejudice, ruled against the plaintiff. Shaw wrote that separate schools were not an infringement on the rights of Blacks if the schools were “separate but equal.”

In 1855, the Massachusetts State Legislature abolished segregated schools, but in 1896, the original Roberts decision became the foundation for establishing the “separate but equal” standard nationwide in Plessy v. Ferguson. It was not successfully challenged until the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954. Roberts’s lawsuit on behalf of his daughter is considered the first legal action taken against segregated schools in the country. As Stephen and Paul Kendrick note in their book Sarah’s Long Walk, “In the end [Roberts’s] brief partnership with Morris was to produce the most important element of this generation’s contribution to our history when the Roberts case began its curious legal trail to the very steps of the United States Supreme Court in 1954.”[6]

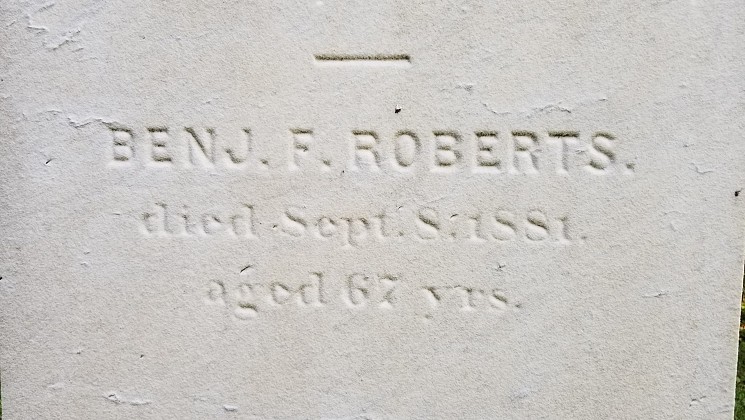

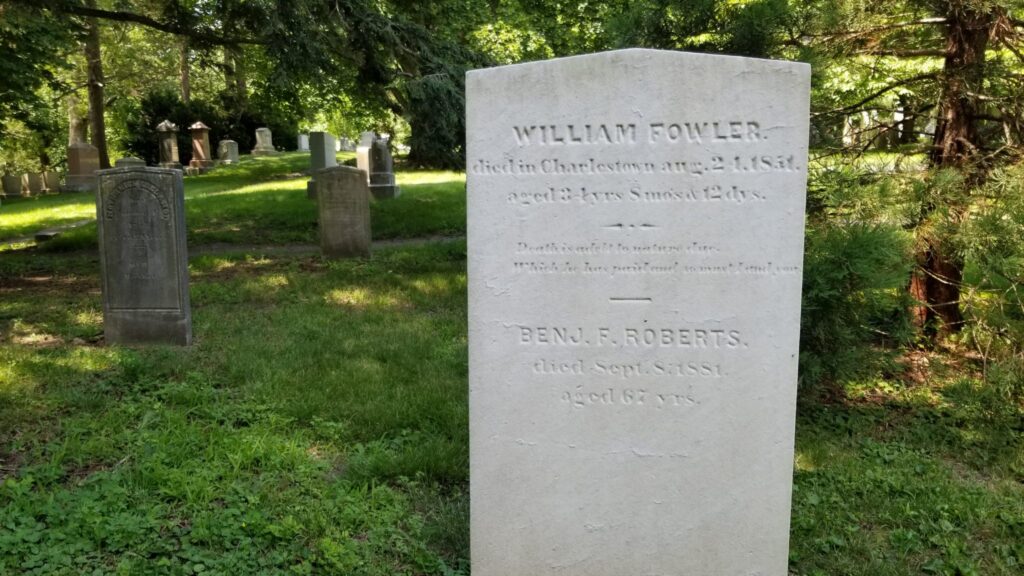

Benjamin Roberts died on September 8, 1881, of epilepsy. His name appears on a thin, slightly tilting gravestone, along with William Fowler, Robert’s father-in-law. Sarah Roberts lived in Boston with her grandfather after her father’s death. She eventually left Boston leaving no record as to her whereabouts—her descendants are actively searching for her burial place.[7]

Benjamin Franklin Roberts is buried in the St. John Lot, Lot 1736 on Fir Avenue.

Footnotes:

[1] Benjamin Roberts, The Self Elevator, March 3, 1853.

[2] Roberts had earlier lost his 20-month-old son Thomas to scarlet fever.

[3] The Abiel Smith School is open to the public today.

[4] Benjamin Roberts, “Report of the Colored People of the City of Boston, on the Subject of Exclusive Schools,” Boston: 1850, in Stephen Kendrick and Paul Kendrick, Sarah’s Long Walk: The Free Blacks of Boston and How their Struggle for Equality Changed America. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004, p. 97.

[5] Charles Sumner, “Equality before the Law, Unconstitutionality of Separate Colored Schools in Massachusetts,” in Sarah C. Roberts vs. The City of Boston. The Supreme Court of Massachusetts.1849.

[6] Stephen Kendrick and Paul Kendrick, Sarah’s Long Walk: The Free Blacks of Boston and How Their Struggle for Equality Changed America. Boston: Beacon Press, 2004, p. 257.

[7] Stephen Kendrick and Paul Kendrick, Sarah’s Long Walk, p. 259..