Adapting the Story of Harriet Jacobs for Children: An Interview with Fatima Seck, ’24-’25 Mount Auburn Artist-in-Residence

Friends of Mount Auburn January 9, 2025 Art | History | Literature | Notable Residents

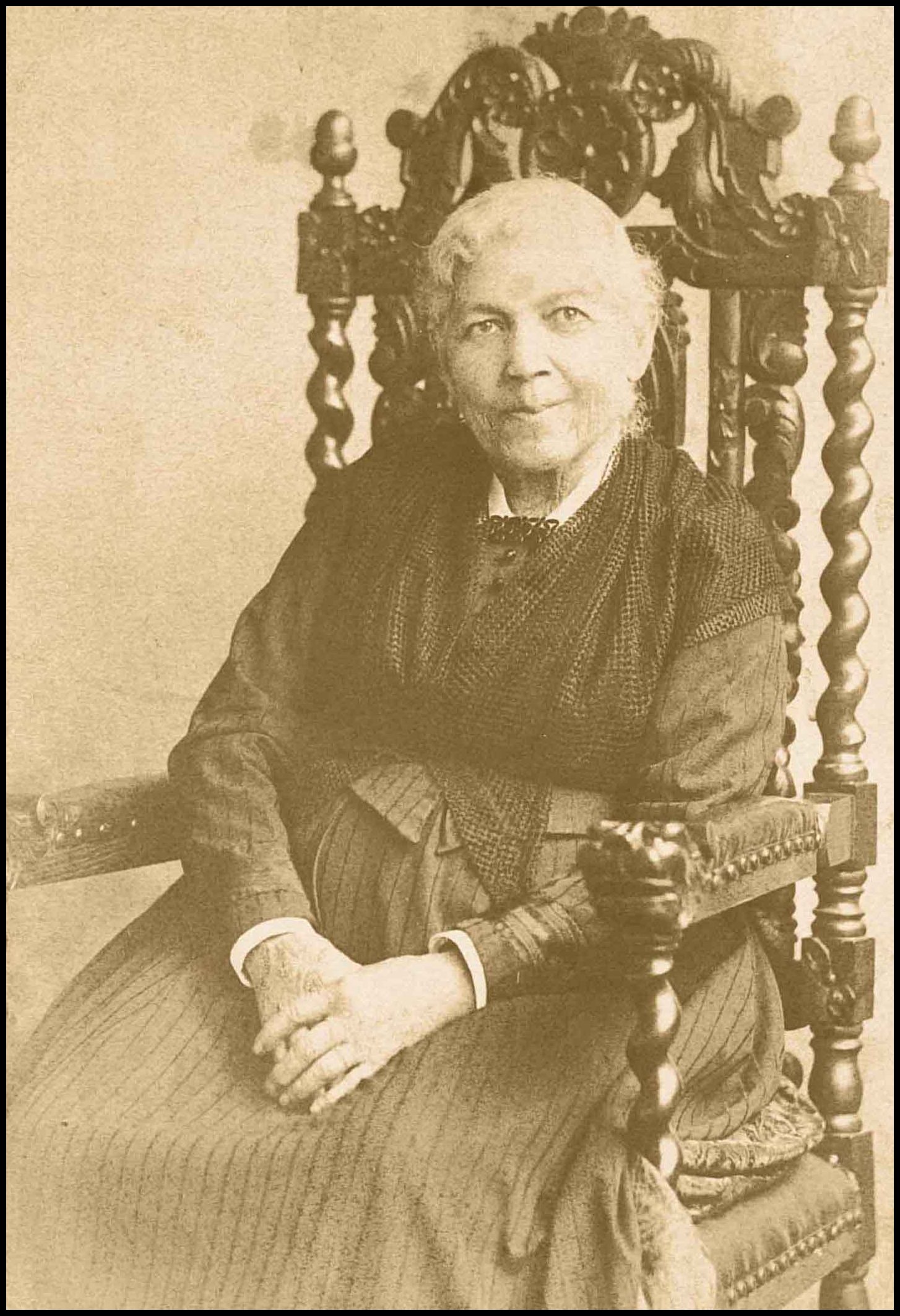

Harriet Jacobs was born in North Carolina in 1813. She escaped enslavement in 1835 and by 1842 made her way to New York City where she was reunited with her daughter and brother. In 1860 she published her autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, making her the first woman to author a formerly enslaved person’s narrative in the United States. Jacobs was also part of the abolitionist movement, raising money for Black refugees and founding two schools for formerly enslaved people. She died in 1897 and is buried at Mount Auburn next to her brother on Clethra Path near Halcyon Lake.

Julie-Anne: Do you remember when you first encountered poetry?

Fatima: My first encounter with poetry was probably Slam Poetry, or spoken word. I must’ve been 11 or 12...I also remember reading “Phenomenal Woman” by Maya Angelou out loud over and over again because it has that rhythmic, musical quality to it...Now, when I think about writing for children, the sing-songy nature of [the poems] feels very tied to my origins in poetry. [Spoken Word] is as much about the words and the language as how you communicate it, and a big part of storytelling with children is reading aloud.

Julie-Anne: Poetry is a particularly powerful form of writing. It has a special kind of magic.

Fatima: I feel that, too. It has a charm. It’s something you can easily hold onto. I feel that way about certain Mary Oliver poems. Her poem “Wild Geese” — I put that in my pocket and just walk with it. Longer forms of writing are beautiful and interesting in their own ways, but there is something special about the punch of a poem, and how bite-size it is.

Julie-Anne: Big power in a small package.

Fatima: Yes! It’s delightful, isn’t it? The feeling of a poem coming together at the end— it's exhilarating.

Julie-Anne: When did you start writing poetry? What is it about this medium that speaks to you?

Fatima: I started writing poetry in college when I was doing a lot of analytical writing. In fact-based, well researched essays, there’s a level of feeling that’s not being expressed. So, I felt more of a need for poetry at that time.

Julie-Anne: There was freedom in it.

Fatima: Yes, exactly. It was a kind of liberation. There was something healing in making meaning for myself and searching for metaphors that made every type of knowledge legitimate—not just the knowledge that can be cited and researched and “proven.” Poetry had a kind of deeper human feeling and meaning.

Julie-Anne: What kind of poems were you writing back then?

Fatima: It was a little bit of everything...It was a way to answer some questions. Some things stay with you a little longer and poetry can be a way to say: let me look at you. What is here? Let’s break this open...Poets are meaning-makers. It’s about searching for the grand and the large in the small thing, in this one moment. How is something larger passing through this? ...I think that’s why I found a home in poetry. I’m a big questioner, and poetry feels like an attempt to find answers. I mean, there's never an answer—but there is an attempt to search.

Julie-Anne: The search is forever. But there’s a lot of play and fun and adventure and learning and growing in that search.

Fatima: Yes! That’s what creates you. It’s not having the answer. The creative process is the discovery...And, you know, it can take a while to find a poem. Writing isn’t always a quick or easy process. Sometimes you just need to walk around the Cemetery and let [the poem] find you.

Julie-Anne: When did you first learn about Harriet Jacobs? How did she come into your life?

Fatima: I was reintroduced to Harriet Jacobs’ story through the work of Simone Leigh—an incredible Black woman artist who makes these beautiful grand sculptures. She represented the United States at the Venice Biennale in 2022...and during her show they had something called the Loophole of Retreat which was a gathering of Black women (i.e. scholars, performers, writers, and artists) and the name for that gathering came from Harriet Jacobs. Harriet wrote about hiding in her grandmother’s attic for seven years and she called that hiding place her “loophole of retreat.” I was teaching at the ICA* at the time and giving tours on Simone Leigh when I started learning more about Harriet Jacobs who is known as the first Black woman to have written a first-person narrative about the experience of being enslaved. She was about six years old at the beginning of the narrative, and there are so few accounts of Black childhood during slavery. That’s when I became very interested in that particular part of her story. Black women’s history has always been a big focal point for me, so she has come up before, but in these last couple of years she started to loom a little larger.

Julie-Anne: It sounds like she found you.

Fatima: I do sometimes think of it that way. Sometimes historical people can loom large on your heart and your mind. There’s reciprocity there—like they’ve chosen you as much as you’ve chosen them...When you’re spending so much time with someone it can feel like they’re a real person you’ve known.

Julie-Anne: Jacobs’ autobiography deals with difficult, mature, complex material. What parts of her story will inform your children’s book?

Fatima: I’ve been thinking a lot about how to teach slavery to children, especially in the context of how deeply gruesome and violent an experience it was for people—and I have a lot of thoughts about that—but a big part of it is starting with what experiences they share. That’s why I find the first few years of the account of her life so interesting. She was a child, and she didn’t know she was enslaved.

Julie-Anne: Until her mother died.

Fatima: Yes—when she was six. And I started thinking about the liberation her mother created for her—a kind of internal liberation—and how powerful that was to have...There was this short period of time when she was just thinking about the land, her mother, the things they would do every day, what they would eat. So, that’s what I’m focusing on in my book—her childhood, her relationship with her mother, and her time in this domestic sphere.

Julie-Anne: And it’s possible that there are some children who will read your book who, just like Harriet, lost their parent(s) at a young age.

Fatima: That makes me think about how we talk about grief with children and how death is this thing we’re told not to talk about with kids. But they’re already living it. They know it’s happening. So, with this project, yes, it’s about Harriet Jacobs but it’s also about bringing kids to a Cemetery and talking about what Cemeteries are for and what role they play in people’s lives.

Julie-Anne: Have you found in your work with young people that they are more open or receptive to talking about difficult things?

Fatima: I think they’re grateful for the opportunity. Just today, at the garden I work at, we buried a rabbit. And all the kids seemed grateful to have the opportunity to be kind to this rabbit, to leave it flowers, and ask people to step over the place it was buried. Whenever we can facilitate those opportunities for children, I think they feel a little more liberated.

Julie-Anne: There’s grief about so many things when you’re growing up. You lost your favorite toy, or you changed schools and had to leave your friends and your favorite teacher—

Fatima: Or you moved out of your childhood home. Or your body changes. They’re feeling all of these things and recognizing that they’re happening, but they don’t necessarily have the language to express it—and we can help with that.

Julie-Anne: What do you hope children, educators, and parents will take away from this book?

Fatima: One way the book can be a useful tool beyond something that teaches us about the history of Harriet Jacobs is that it’s a tool for bringing young people to the Cemetery. I want it to be a participatory experience. Let’s read this book in our classroom and then take a field trip to Mount Auburn. It creates an automatic tie to a place right here in Boston where you can bring your young person or your student to a space that helps to break some of the silence and fear around death and dying. Let’s not be afraid. Let’s feel love, compassion, and curiosity instead. We can liberate children by speaking to them about grief...Art can create an opportunity for that, and it can start by saying, “let’s read this poem together...”

-----------------------------------------------------------------------

*Between April-September 2023, the Institute of Contemporary Art Boston hosted an exhibition of Simone Leigh’s landmark Venice presentation which “centered the experiences and intellectual labor of Black femmes.”

Comments

Comments for this post are closed