Mount Auburn Consecrated

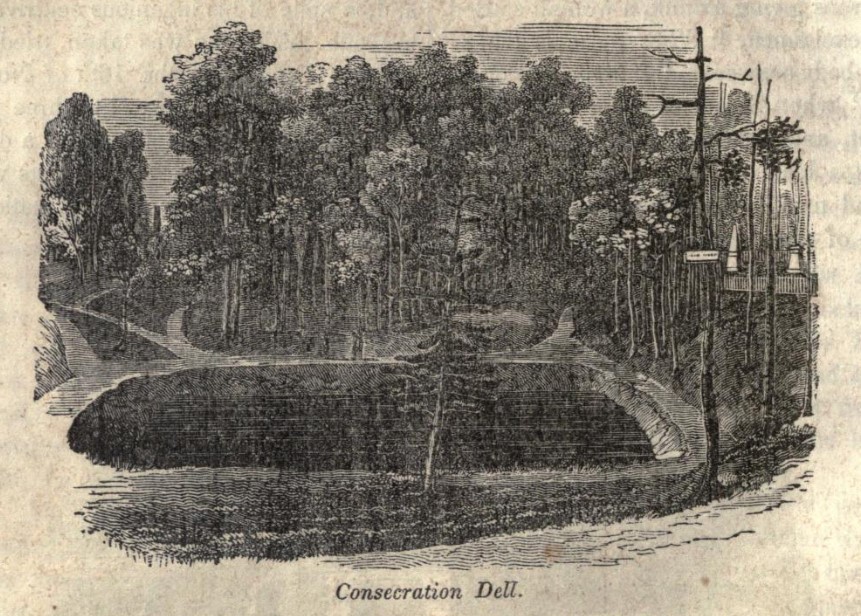

In 1831 the Massachusetts Horticultural Society purchased 72 acres of mature woodland situated in Watertown and Cambridge for the creation of a “rural cemetery” and experimental garden. On September 24, 1831, a crowd gathered in the Dell, the natural amphitheater located in the heart of the Cemetery, for the ceremony to consecrate this sacred land.

Newspapers described a crowd of more than 2,000 people who came from Boston and surrounding communities to participate in the dedication of the Cemetery–a burial place that might “be subservient to some of the highest purposes of religion and human duty.” Following the prayer offered by Henry Ware, a leading Unitarian minister and the Hollis Professor of Divinity at Harvard, the crowd of spectators joining in chorus to sing a new hymn written just for the occasion by Reverend John Pierpont. Joseph Story, an Associate Supreme Court Justice, the Dane Professor of Law at Harvard and Mount Auburn’s first president, then delivered the ceremony’s main address.

Story, who was still mourning the loss of his ten-year old daughter to scarlet fever, delivered a powerful address that outlined the founders’ intentions in creating the new Cemetery:

My Friends, –

The occasion which brings us together, has much in it calculated to awaken our sensibilities, and cast a solemnity over our thoughts. We are met to consecrate these grounds exclusively to the service and repose of the dead. The duty is not new; for it has been performed for countless millions. The scenery is not new; for the hill and the valley, the still, silent dell, and the deep forest, have often been devoted to the same pious purpose. But we address feelings intelligible to all nations, and common to all hearts.

…It is to the living mourner – to the parent, weeping over his dear dead child – to the husband, dwelling in his own solitary desolation – to the widow, whose heart is broken by untimely sorrow – to the friend, who misses at every turn the presence of some kindred spirit. Thus, these repositories of the dead caution us, by their very silence, of our own frail and transitory being. They instruct us in the true value of life, and in its noble purposes, its duties, and its destination. They spread around us, in the reminiscences of the past, sources of pleasing, though melancholy reflection.

We dwell with pious fondness on the characters and virtues of the departed; and, as time interposes its growing distances between us and them, we gather up, with more solicitude, the broken fragments of memory, and weave into our very hearts, the threads of their history. As we sit down by their graves, we seem to hear the tones of their affection, whispering in our ears. We listen to the voice of their wisdom, speaking in the depths of our souls. We shed our tears; but they are no longer the burning tears of agony. They relieve our drooping spirits. We return to the world, and we feel ourselves purer, and better, and wiser, from this communion with the dead.

(abridged excerpt taken from Joseph Story’s Address Delivered on the Dedication of the Cemetery at Mount Auburn, September 24th, 1831.)

Boston Courier's Account of the Consecration

The Boston Courier’s account of the public Consecration of Mount Auburn Cemetery, September 24, 1831.

An unclouded sun and an atmosphere purified by the showers of the preceding night, combined to make the day one of the most delightful we ever experience at this season of the year. It is unnecessary for us to say that the address by Judge Story was pertinent to the occasion, for if the name of the orator were not sufficient, the perfect silence of the multitude, enabling him to be heard with distinctness at the most distant part of the beautiful amphitheatre in which the services were performed, will be sufficient testimony as to its worth and beauty. Neither is it in our power to furnish any adequate description of the effect produced by the music of the thousand voices which joined in the hymn, as it swelled in chastened melody from the bottom of the glen, and, like the spirit of devotion, found an echo in every heart, and pervaded the whole scene.

The natural features of Mount Auburn are incomparable for the purpose to which it is now sacred. There is not in all the untrodden valleys of the west, a more secluded, more natural or appropriate spot for the religious exercises of the living; we may be allowed to add our doubts whether the most opulent neighborhood of Europe furnishes a spot so singularly appropriate for a “Garden of Graves.”

In the course of a few years, when the hand of Taste shall have passed over the luxuriance of Nature, we may challenge the rivalry of the world to produce another such abiding place for the spirit of beauty. Mount Auburn has been but little known to the citizens of Boston; but it has now become holy ground, and “Sweet Auburn, loveliest village of the plain,”—a village of the quick and the silent, where Nature throws an air of cheerfulness over the labors of Death,–will soon be a place of more general resort, both for ourselves and for strangers, than any other spot in the vicinity. Where else shall we go with the musings of Sadness, or for the indulgence of Grief; where to cool the burning brow of ambition, or relieve the swelling heart of disappointment? We can find no better spot, for the rambles of curiosity, health or pleasure; none sweeter, for the whispers of affection among the living; none lovelier, for the last rest of our kindred.