Mary Walker (1818-1873)

Freedom Seeker, Seamstress, & Caretaker

Mary Walker began her life enslaved in North Carolina, where she lived on the large plantation of Duncan Cameron. Walker learned the skills of a seamstress and became a caretaker of Cameron’s daughters. She often accompanied the family on medical trips to Philadelphia for Duncan’s daughter. In 1848, threatened with banishment to the Deep South after the family’s return to North Carolina, she slipped away from her enslavers. She left her mother and three children behind in bondage.

In Philadelphia, Mary Walker became a seamstress to James Lesley. The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 put freedom seekers in the state at peril, so Mary Walker fled to Boston and lived with Lesley’s cousin, J. Peter Lesley and his wife Susan Lesley. Walker, however, felt the deep pangs of being separated from her mother and children. In 1859, J. Peter Lesley wrote an impassioned letter to Walker’s enslaver, Mildred Cameron, of Raleigh telling her of Walker’s agony: “I have seen how sick at heart she is about her mother . . . . Her heart is slowly breaking. She thinks of nothing but her children . . . . Her mother-heart yearns unspeakably after them.”[1] Mildred Cameron never replied.

Over the years, the Lesleys and others, including Frederick Douglass and Harriet Beecher Stowe, helped Mary Walker in her struggle to reunite with her children. “Though many abolitionists renounced ransom or personal appeals to slave-holders as concessions to the crime of slavery, Mary Walker found friends who understood her anguish and who were willing to commit themselves to redeem her children,” Sydney Nathans, author of To Free a Family: The Journey of Mary Walker, writes. “Together or separately, they ventured half a dozen attempts at liberation, from ransom to ruse to rescue.”[2] Walker’s son Frank escaped in 1852. After the Civil War, Walker was finally reunited with her other children Agnes and Bryant Walker.

Mary Walker became known in Cambridge for her skills as a seamstress and a caretaker. She worked for years for the sisters of Sarah Robbins Howe. In gratitude Howe’s sons, James Murray Howe and Estes Howe, purchased a home for Walker on 54 Brattle Street in Cambridge. Known as the Blacksmith House, it had previously been the dwelling of Dexter Pratt, whom Henry Wadsworth Longfellow brought to fame in his beloved poem, “The Village Blacksmith.” Today the house is the site of the Cambridge Center for Adult Education.

Mary Walker and other family members, including Agnes Burgwyn and her husband James Burgwyn, and Bryant Walker and his wife Annie Gorey, lived in the house 42 years, longer than any other resident. “As long as her family lived in the Brattle Street house . . . . They would have around them people who knew who they were, who knew of Mary Walker’s story and strivings, who were ready to help,” Nathans writes. “. . . . Home and haven, the Brattle Street house remained in Mary Walker’s family until 1912.”[3]

Mary Walker died in 1872 at the age of 54. She was buried in Mount Auburn among the community of people with whom she had lived, including Sarah Howe and eventually Howe’s son Estes Howe. When John Jacobs, the brother of Harriet Jacobs and a good friend of the Walker family, died, Agnes Burgwyn and her husband, James Burgwyn, buried him in their family lot. In 1875, John Jacobs’s sister, Louisa Jacobs, bought a plot near the Walkers and had John Jacobs’s body reinterred there.

Agnes Burgwyn commissioned a monument to be built in 1895, one year after her brother Bryant Walker’s death. Bryant was a talented gardener, and one of the spaces he lovingly designed was the family burial lot at Mount Auburn. Agnes Burgwyn gave special instructions to Mount Auburn that after the installation of the memorial, which would disrupt the plantings, her brother’s landscape design should be recreated according to the original plan.

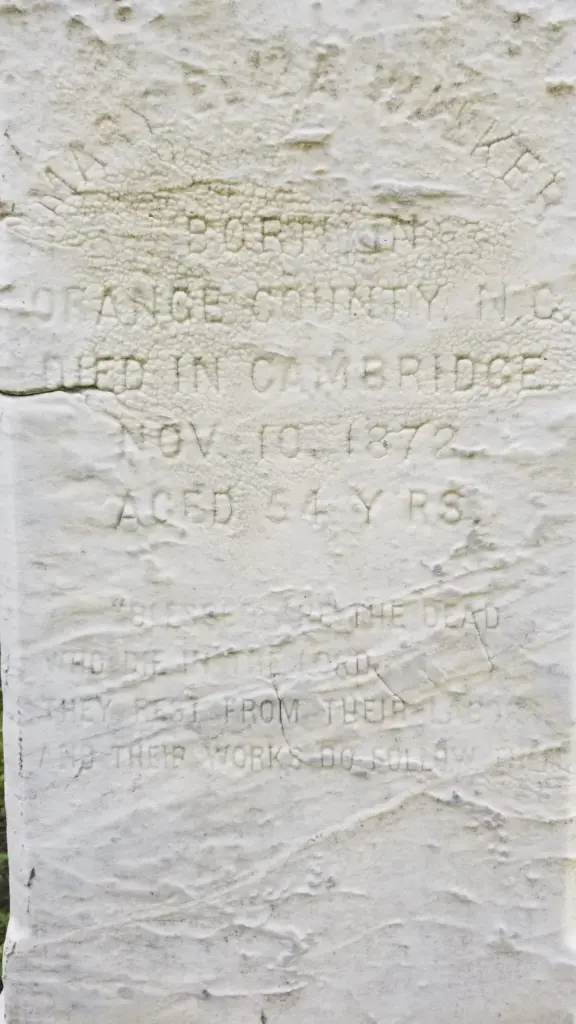

A seven-foot tall obelisk was commissioned for the memorial. The inscription on the magnificent marble monument reads: “Blessed are the dead, Who die in the Lord, They rest from their labor, And their works do follow them.” The epitaph for Mary Walker reads: “Mary Walker, Born in Orange Country, North Carolina, Died in Cambridge, November 10, 1872,” and the adjacent side for her beloved son reads, “Byrant Walker, Born in Raleigh, North Carolina, Died in Cambridge, Age 50.” With donations on behalf of the African American Heritage Trail, Mount Auburn has preserved the entire memorial and reattached the delicate marble dove now perched at the top. A symbol of purity, the dove spreads its wings, as though in flight—toward freedom or in passage to the next world.

Mary Walker is buried in Lot 4312 on Kalmia Path.

Footnotes:

[1] J. Peter Lesley to Mildred Cameron, September 4, 1859, Cameron Family Papers, Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in Sydney Nathans, To Free A Family: The Journey of Mary Walker. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012, p. 3.

[2] Sydney Nathans, To Free A Family: The Journey of Mary Walker. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2012, p. 3.

[3] Nathans, To Free A Family, p. 252.