The Egyptian Revival Gateway: Mount Auburn’s First Iconic Image

Melissa Banta June 25, 2012 Archives | History

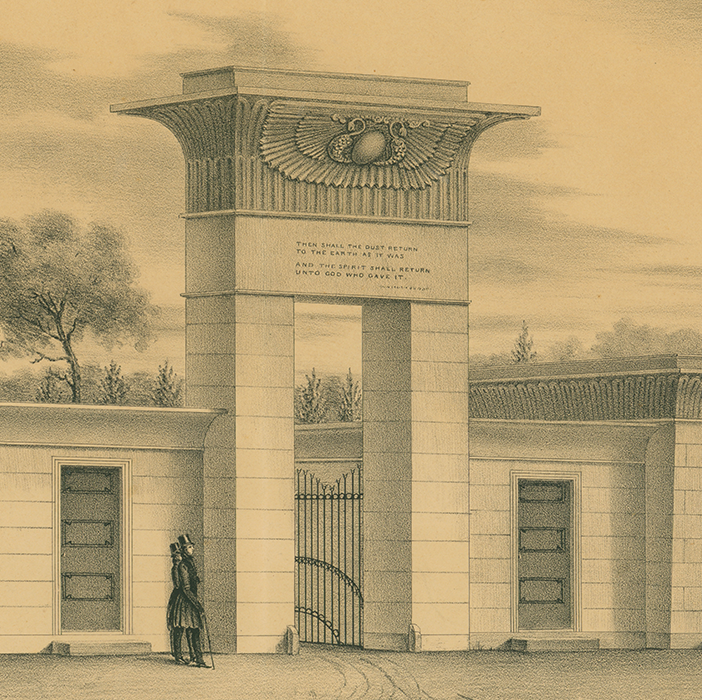

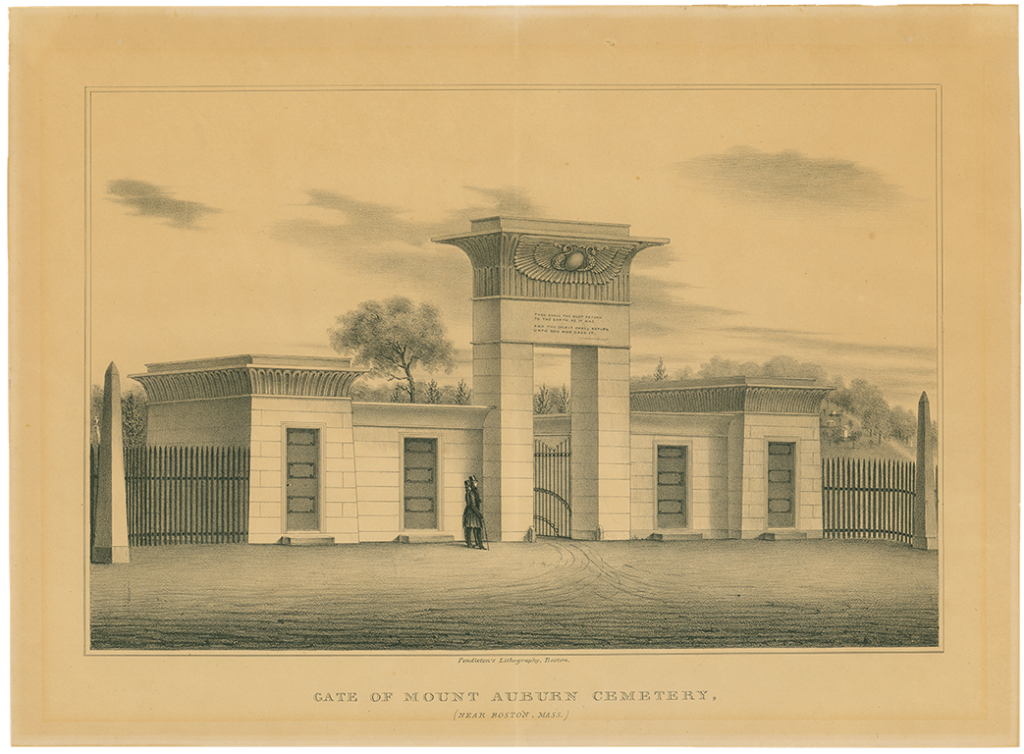

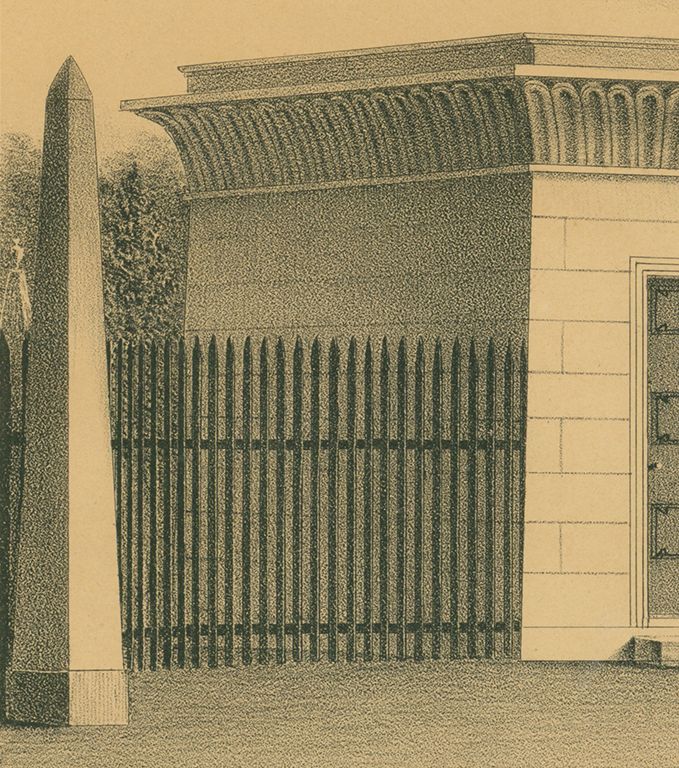

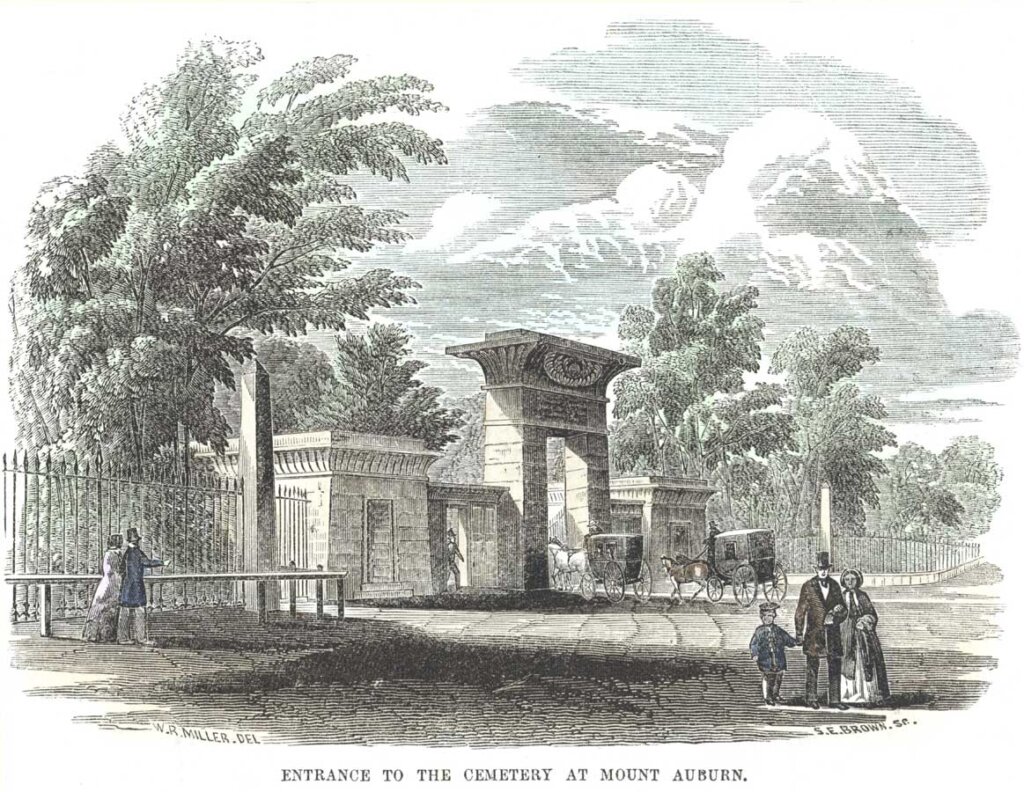

On first viewing, there appears to be no discernible difference between the gateway as illustrated in the 1834 lithograph and that shown in later prints. But on close examination a telltale clue reveals itself in the fence on either side of the gateway. The simplicity of the fence in the lithograph contrasts with the elaborate design depicted in later prints.

Dr. Jacob Bigelow, one of Mount Auburn’s original founders, recounted at a meeting of the Garden and Cemetery Committee of the Massachusetts Historical Society on September 1, 1832:

“It was voted ‘That the model for a gateway and lodges, produced by Dr. Bigelow, be adopted, and that Gen. Dearborn, Dr. Bigelow, and Mr. Brimmer, be a Committee to cause the gate and lodges to be constructed of wood agreeably to said model.’ This model was intended as a pattern for a corresponding structure, to be afterwards executed in stone, when the Corporation should be able to meet the expense.”1

Thus the 1834 lithograph, made not long after the completion of the entranceway, illustrates the fence constructed in wood, not cast iron. The gateway, also constructed in wood, was painted gray and dusted with sand when it was still wet so as to give the appearance of granite. The faux granite structure, which cost $1,366, did not appeal to everyone. The Picturesque Pocket Companion through Mount Auburn, published in 1839, noted that the material of the gateway “has not escaped criticism. Many persons are dissatisfied with even a good wooden imitation of stone.”2 An out-of-town visitor described it as “a paltry deception,” questioning “the taste that could paint wood in imitation of granite at the entrance of a City of the Dead. . . . In a city like Boston rich beyond most others and proverbial for its liberality, [cost] never ought to be an obstacle.”3

Bigelow, the designer of the gateway, chose Egyptian symbolism as the dominant motif, another aspect of the new entranceway that was not universally embraced. In 1847, Cornelia Walter observed in Mount Auburn Illustrated, “As regards monuments or designs of the Egyptian style, for places of Christian interment, we are aware that an objection made to them has been, that they mark a period anterior to Christian civilization—a period of relative degradation and paganism; but it has ever been a pleasure with the thoughtful, to look beyond the actual appearance of a figure, to the right development of its original idea.”4

Public fascination with ancient Egypt had first been ignited by Napoleon’s campaign into the country and the many lavishly illustrated publications, such as Description de l’Egypte, that followed. Bigelow, a skilled draftsman and designer himself, appreciated that, “No man can look upon the splendid ruins of Karnac, without feeling humbled by the greatness of a people who have passed away.”5 As scholar Blanche M. G. Linden writes, “Bigelow and others interpreted Egyptian style as promise and symbol of permanency. . . . It was intrinsically historic as well as sublime.”6

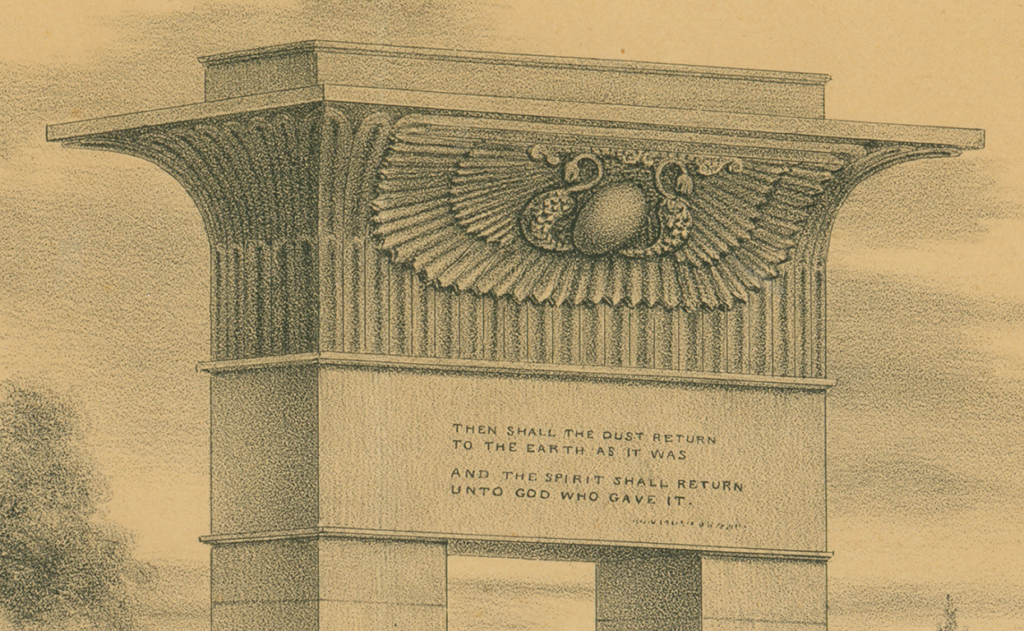

Bigelow noted that the outline of the Mount Auburn gateway was “mostly taken from some of the best examples in Denderah and Karnac.” 7 His plan incorporated a winged globe carved into the cornice. In her defense of Bigelow’s design, Walter wrote, “We do not know of a more fitting emblem than this for the abode of the dead, which we may well suppose to be overshadowed with the protecting wings of Him who is the great author of our being—the ‘giver of life and death.’”8 Bigelow chose an inventive way to address concern that visitors might be offended by the Egyptian practice of placing a serpent or crocodile head on the sides of the globe. Instead he designed a drooping lotus, as he explained, “to conceal the head of the fabulous animal.”9 On each side of the 25-foot-gateway, Bigelow positioned two obelisks connected to lodges by a fence.

By 1842, when Mount Auburn had established a more secure financial footing and the technology of granite cutting had improved, the wooden edifice served as a model for a new structure made of granite. The firm of Octavius T. Rogers of Quincy built the stone gateway for $9,535. The Rogers quarries supplied and cut the granite blocks, which they transported in barges via the Charles River and then by oxen to Mount Auburn. The edifice, like its wooden predecessor, was 25 feet high and 60 feet long. A noted engineering feature was the single monolithic cornice stone, 22 feet long, created from one solid block of granite, the largest sculptured granite piece in America at the time.10

Illustrative prints created after the completion of the new granite gateway also reveal that the Cemetery had replaced the original wooden palisade fence with a decorative cast iron fence. Constructed by Adams, Whitredge and Cummings of Boston and designed by Bigelow, the new iron fence incorporated decorative lotus flower pickets done in an Egyptian Revival style.

Additions to the entrance over time included side gates, turnstiles, replacement of the central gate in an Egyptian Revival design, and modifications in the doors and windows of the lodges. In their 1981 report to the Cambridge Historical Commission, “Proposed Landmark Designation for the Mount Auburn Cemetery Gate and Fence,” Arthur Krim and Charles Sullivan observe that other than these changes “in all other respects the granite gateway and cast iron fence of Mount Auburn remain intact . . . following the original Egyptian Revival design of Jacob Bigelow from 1831.”11

Mount Auburn’s gateway immediately assumed special significance as the first fully created Egyptian Revival structure in the United States and the first complete Egyptian Revival design for an American cemetery. “The unprecedented addition of such a ceremonious entrance, more elaborate than those of Boston’s new churches, indicates the complexity of new notions about the cemetery and expectations that it would be a place of great civil and cultural importance,” Linden contends.12 As such it became a model for other cemetery gateways.

The entrance also came to represent an iconic symbol of Mount Auburn. The public could find representations of the gateway on china, stationery, postcards, guidebooks, and photographs. In the early days of the Cemetery and before the invention of photography in 1839, prints were especially critical in cementing the gateway’s image in the public’s imagination. “The introduction of lithographic printing in the United States in the 1820s revolutionized printmaking and gave rise to a popular visual culture. . . . lithography was the quickest and cheapest medium for printing pictures in volume,” Sally Pierce and Catharina Slautterbach write in Boston Lithography, 1825-1880.13

The early 1834 print was created by Pendleton’s Lithography, one of major lithographic establishments in Boston. The highly successful shop, located on Washington Street in the center of Boston’s commercial printing and publishing district, helped bring exposure of the symbolic image to a broad public.

In the lithograph, several elements draw viewers toward the portal: two men approach the entranceway and tracks made by horse carriage lead into the half-opened gate, inviting visitors into the Cemetery. The inscription on the cornice, from Ecclesiastes 12:7, reads: “Then Shall The Dust Return, To The Earth As It Was, And The Spirit Shall Return, Unto God Who Gave It.” Meg Winslow, Curator of Mount Auburn Cemetery’s Historical Collections, notes, “The print has a calm, still quality that accentuates the idea of Mount Auburn as a sanctuary, away from the bustling city life.” A hint of the sacred, pastoral space can be seen in the tops of the trees behind the entrance and in the rise of the hill dotted with graves to the right of the gateway. Whether in wood or granite, Bigelow’s 1831 design endures, preserving as Krim and Sullivan note, his “original conception for the Mount Auburn entrance as a symbolic portal into the reflective world of the garden cemetery beyond.”14

Sources

1 Jacob Bigelow, A History of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn. Boston and Cambridge: James Munroe and Company, 1859, p. 24.

2N. B. Devereaux, Jr., The Picturesque Pocket Companion Through Mount Auburn Illustrated with Upwards of 60 Engravings. Boston: Otis, Boarders and Company, 1839, p. 83.

3 Wines, Enoch Cobb, A Trip to Boston in a Series of Letters to the Editor of the “United States Gazette.” Boston: Little Brown, 1838, p. 44 in Blanche M. G. Linden, Silent City on a Hill: Picturesque Landscape of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery, Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, p. 215.

4 Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated in Highly Finished Line Engraving . . . with Descriptive Notices. New York: R. Martin, 1847, p. 18.

5 Jacob Bigelow, The Useful Arts Considered in Connexion with the Applications of Science, Vol. 1. Boston: Thomas H. Webb and Co., 1840, p. 131.

6 Blanche M. G. Linden, Silent City on a Hill: Picturesque Landscape of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery. Amherst and Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, p. 213.

7 Bigelow, A History of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn, p. 26.

8 Walter, p. 19.

9 Bigelow, A History of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn, p. 26.

10 Linden, p. 215.

11 Arthur Krim and Charles Sullivan, “Proposed Landmark Designation for the Mount Auburn Cemetery Gate and Fence.” Cambridge Historical Commission, December 3, 1981.

12 Linden, p. 211.

13 Sally Pierce and Catharina Slautterback, Boston Lithography, 1825-1880: The Boston Athenaeum Collection. Boston: The Boston Athenaeum, 1991, p. 1.

14 Krim and Sullivan, p. 7.

Comments

Comments for this post are closed