Mount Auburn, the Rural Cemetery Movement, and Frederick Law Olmsted

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted (1822 – 1903) was nine years old when Mount Auburn was founded in 1831. While he did not design the Cemetery, the enduring characteristics that made Mount Auburn a model for cemeteries and public parks would come to deeply influence his work.

(more…)“A Most Beautiful and Commodious Building” Mount Auburn’s Story Chapel and Administration Building

The first thing you see when you pass through the entry gateway of Mount Auburn Cemetery is Story Chapel and the adjoining Administration Building. Since 1898, the old stone building has provided a setting for funeral and memorial services; a meeting place for public programs and events; and offices where staff have carried out the work of cemetery services, and of preservation and cultural activities related to Mount Auburn. Masonry work, structural repairs, and major renovations on the interior and exterior of the building have been taking place since 2017. The multi-phased project gives us pause to reflect on the significance of the building in Mount Auburn’s history.

Decision to Build a New Chapel and Office

Construction on the original red sandstone structure started in 1896 and was completed in 1898, during a time when Mount Auburn was experiencing significant growth.[i] Bigelow Chapel, Mount Auburn’s first chapel erected in the 1840s and 1850s, had served the Cemetery for half a century. Increasing complaints about the building, however, included insufficient space for funeral services, no cellar or robing room, and poor heating. Bigelow Chapel’s challenging acoustics, as reported in a Mount Auburn Annual Report, became evident in the form of a “disagreeable echo, which interfered with the voice of the officiating minister and rendered choir singing impracticable.”[ii]

In 1895, a special committee appointed to investigate the renovation of Bigelow Chapel concluded that refurbishing the building would be equal to the cost of constructing a new structure.[iii] In addition, more space was needed for the Cemetery’s growing administrative staff. The committee recommended to the trustees the “construction of a new Chapel, and at the same time, and in connection therewith, a building for the offices of the Corporation. . . . By connecting the two buildings, both can be more conveniently and economically heated, and cared for.”[iv] The cost of construction totaled approximately $68,000.[v]

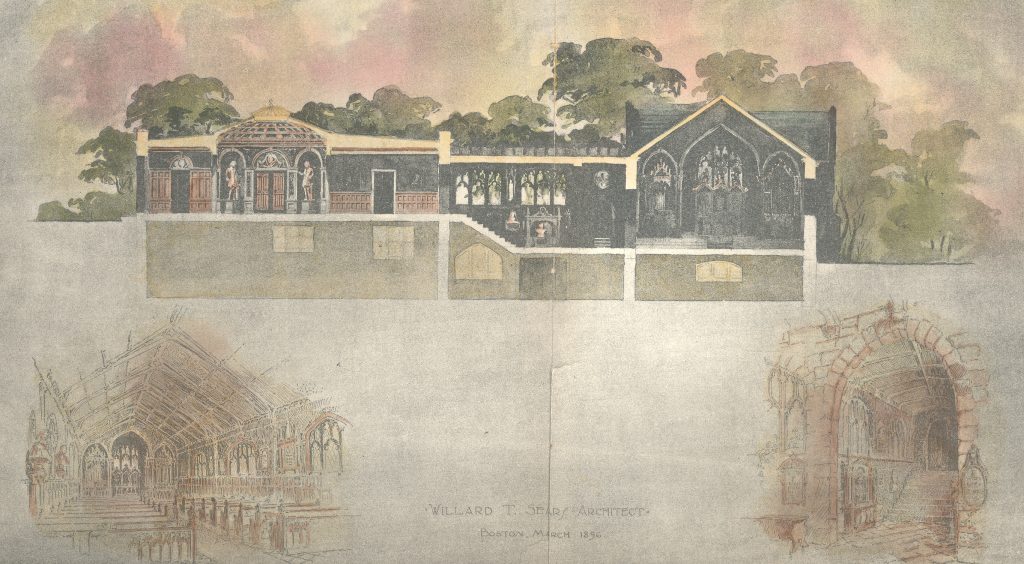

The trustees expressed their desire for a style of building in keeping with the other architectural landmarks within the Cemetery including the Egyptian Revival Gateway and Bigelow Chapel. A design competition included plans submitted by the architectural firms Longfellow, Alden and Harlow; Coolidge and Wright; G. Wilton Lewis; and Willard Thomas Sears.[vi] Sears, the chosen architect, designed the Old South Church in Boston’s Copley Square (1873), and was currently working with Isabella Stewart Gardner on Fenway Court, the home of Mrs. Gardner that later became the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (1900-1902). [vii] Sears would also oversee the interior renovation of Bigelow Chapel in 1899 for the installation of a new crematory.

New Chapel

Sears chose red sandstone quarried in Potsdam, New York for the construction of the Chapel and administrative offices.[viii] The stone was understood to be weather resistant and harder than granite, yet easy to carve. It was also known for its variegated colors that ranged from red to pink. Mount Auburn’s Annual Report noted that Potsdam sandstone “is a very hard stone and does not readily absorb moisture, and the color is very agreeable and pleasant to the eye. The buildings will be practically fireproof, built in the most durable manner.”[ix]

Israel Spelman, President of Mount Auburn during the time of the building’s construction, described Sears as “unremitting in his superintendence and personal attention.” [x] For the “New Chapel,” as the building was initially called, Sears explained, “The English perpendicular style of architecture as exemplified in many of the English parish churches built during the early part of the fifteenth century has been adopted.”[xi] The English gothic style was characterized by arches in the ceiling, large windows, and vertical lines in the paneling and window tracery (the support between sections of glass).

In the New Chapel, Sears placed Indiana limestone tracery along the windows and the interior wall between the nave (central part of the chapel) and the cloister (hall) running along the north side of the building. In 1929, the architectural firm Allen and Collens oversaw the installation of leaded and stained glass windows in the nave and the chancel (area near the altar). For the nave, the studio of Wilbur H. Burnham Sr. created gothic revival windows representing the medieval tradition that was favored by Burnham. The figures of Christ and angels are portrayed in the large chancel window above the altar and are signed by the Boston artist Earl E. Sanborn. While the symbolism is Christian, Sears designed the Chapel “to meet the requirements of all religious denominations.”[xii]

The interior walls were constructed with Pennsylvania golden bricks and laid in yellow mortar. The Chapel featured carved wooden hammer beams (horizontal supporting beams) with decorative angels, each holding a shield; carved wooden pulpits (elevated stands for speakers); and a total of 22 pews, 11 on each side of the aisle. All were made of Florida gulf cypress that reflect the Arts and Crafts aesthetic, and the woodwork was stained and rubbed down to achieve a flat oil finish. Together the pews and balcony, accessible by a stairway from the front vestibule, offered seating for 175 people, more than twice that of Bigelow Chapel. An organ chamber housed a Hutchings organ, which was replaced in 1925 with a Hook & Hastings model.[xiii] The vestry provided an office and changing room. A room near the Chapel entrance received caskets for funeral services. Unlike Bigelow, the New Chapel also had electricity.

Visitors entered the New Chapel on Central Avenue through a porte-cochere (covered porch). For the exterior, Sears designed a square three-story belfry (bell tower) with a turret and a spire (removed in 1935). Flat roof areas were covered with copper and the pitch roofs with slate. A sundial mounted on a tablet made from Indiana limestone was placed on the southern exterior of the building. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch acquired the bronze sundial from its previous owner Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. The tablet is carved with ivy leaves, and clusters of engraved ornamental leaves surround the sundial. Bowditch’s son remembered that “My father . . . asked his friend, the poet John G. Whittier, for an appropriate verse to be engraved upon the [tablet].”[xiv]

The 1899 Annual Report observed, “The chapel . . . is furnished with every modern convenience and improvement, and the humblest as well as the most costly and expensive funeral services can there be satisfactorily performed.”[xv] The first funeral occurred on June 18, 1898, and 58 services took place in the first year. [xvi] In 1936, the New Chapel was named Story Chapel after Justice Joseph Story, one of the Cemetery’s founders and its first president.

In 1987, renovations in Story Chapel created improved space for lectures, events, and exhibits. The Visitors Center, located at the entrance to the Chapel, opened in 2008. In 2012, McGinley, Kalsow, & Associates built a new porte-cochere out of reclaimed southern yellow pine and created a more accessible and inviting entrance to the Chapel.[xvii]

Administration Building

The original design of Willard Sears included enclosed cloisters along the north wall and a passageway in the basement that connected the Chapel to the office (which became known as the Administration Building around 1900). There were staff offices on the first floor and basement as well as two fireproof storage vaults for safe storage of Cemetery records. The building provided a superintendent’s office, a meeting room for the trustees, and a business office for a bookkeeper and clerks.[xviii]

The office featured a center rotunda area that exhibited full-length marble statues of John Winthrop, John Adams, James Otis, and Joseph Story. The statues were moved from their previous location in Bigelow Chapel to be displayed in this new setting. In the 1930s, to create more office space, the trustees donated the four statues to Harvard University. [xix] In 1990, Ann Beha Associates renovated the interior in a way that modernized the office space and preserved the structure’s historic features. The skylight in the original rotunda used to display the statues, for example, was replaced with a lantern shaped light that brought natural light into the new offices.

A climate-controlled storage room was built on the lower level to preserve and increase longevity of the Cemetery’s historical collections and archives. In 2015, the family room and conference room where visitors first enter the Administration Building were redecorated. Today, Mount Auburn staff continue to carry out administrative, cultural, and preservation activities related to the Cemetery and to provide essential cemetery services.

When Story Chapel and the Administration Building were completed in 1898, the local press provided extensive coverage about the new structure. The Cambridge Chronicle wrote, “Externally, the chapel is replete with characteristic points of Gothic architecture. Window arches, buttresses, finials, roof effects, etc., are worked into a complete and harmonious structural scheme.”[xx] It described the structure as “a most beautiful and commodious building . . . . the only purely Gothic type of building this side of the Hudson [R]iver and the only one in New England.”[xxi]

While Story Chapel and the Administration Building have undergone changes over time, the historical integrity of the structure has been preserved. The current project, for example, includes restoration of the exterior stonework. Gus Fraser, Vice President of Preservation & Facilities, explains that “it was essential to select a replacement stone that would blend with the rich, reddish, earthy hues of the original Potsdam sandstone and complement the building’s characteristic glow in the afternoon light.” The multi-year project that began in 2017 ushers in a new chapter that continues a tradition of thoughtful renovations to preserve and enhance the historic building. Within its walls, staff dedicate themselves to the mission of the Cemetery and visitors continue to find solace and inspiration.

[i] Mount Auburn raised part of the funds designated for the cost of the new building by selling property it owned across from the Cemetery on Mount Auburn Street. Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, October 18, 1895, Special Meeting, 173.

[ii] Israel Spelman, Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1896, published 1897, 3.

[iii] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, October 18, 1895, Special Meeting, 173.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, December 16, 1898.

[vi] Mount Auburn paid $100 to the architectural firms that submitted plans for the Chapel.

[vii] Willard Sears also designed the Pilgrim Monument in Provincetown (1907). Sears (1837 – 1920) is buried at Mount Auburn on Excelsior Path.

[viii] The Potsdam quarries, in use in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, supplied stone for buildings in New York State, New England, and Canada.

[ix] Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1896, published 1897, 4.

[x] Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1898, published 1899, 4.

[xi] Willard Sears, Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1896, published 1897, 4.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, October 21, 1925. Minutes note that it was voted “that a new organ be bought from Hook & Hastings Organ Company for $7000, and allowance of $600 being made for the old organ making the net cost $6400.” Founders of the company, Elias Hook (1805-1881) and George Greenleaf Hook (1807-1880) are buried at Mount Auburn on Sorrel Path.

[xiv] Vincent Y. Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, Vol. 1 (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902), 239.

[xv]Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1898, published 1899, 4.

[xvi] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, December 16, 1898.

[xvii] The Cemetery removed the original porte-cochere at the Chapel entrance in 1971 as the stone was in poor condition and the entrance did not easily accommodate modern hearses and automobiles.

[xviii] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, December 16, 1898.

[xix] The 1934 Annual Report noted, “It has been decided to give up the Boston office and consolidate the executive offices at Cambridge. . . . Not only will the consolidation result in a substantial saving in operating costs but it will eliminate duplications of work and promote greater efficiency of administration.” Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1834, published 1935, 4.

[xx] “New Mount Auburn Chapel,” Cambridge Chronicle, October 1, 1898.

[xxi] Cambridge Chronicle, September 3, 1898.

Support Preservation at Mount Auburn

The William C. Clendaniel Preservation Fund supports the specialized care that keeps our unique collections in good condition for years to come.

Mount Auburn Cemetery was designated a National Historic Landmark because of its exceptional historic landscape, which consists of both plants and built objects. When you visit, you are surrounded not only by nature but by the evolving history of funerary art in America – monuments, fences, stained glass, and other decorative items that families have chosen to remember their loved ones or that decorate our landscape and buildings.

Mount Auburn’s monuments feature the work of some of our country’s finest 19th-century sculptors, including Horatio Greenough, Edmonia Lewis, and Thomas Crawford. The stained glass in each of the chapels is the work of both Scottish and American craftsmen. More recent monuments reflect the work of contemporary artists and reflect the broadening demographics of the nation. Archival materials help tell the story of how these works of art were created. Taken together, all these elements document changes in commemorative art over the years, with evocative designs and inscriptions that help tell the stories of our residents and our national history. Made of marble, granite, slate, and even glass, this diverse collection is an essential part of our landscape’s beauty, educational value, and historical significance.

Because it is located outdoors, this collection of funerary art requires constant and specialized preservation to survive years of exposure to the elements. Acid rain and snow have already diminished many important details of marble monuments in particular, and high-level care is essential to protect all these items for future visitors.

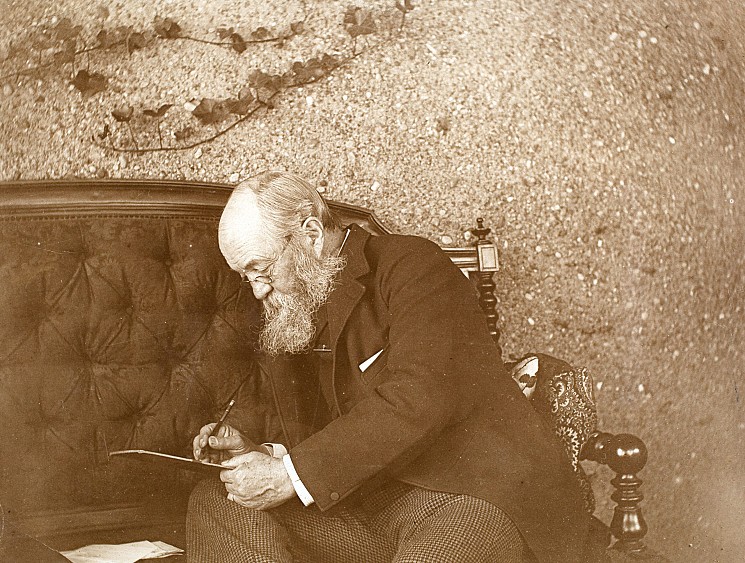

To ensure that the Cemetery has the resources for this enormous but vital task, we have established the William C. Clendaniel Preservation Fund to support critical preservation work across the Cemetery. This endowed fund honors President Emeritus William C. (Bill) Clendaniel, who served as Mount Auburn’s President from 1988 until 2008.

Bill was a passionate advocate for preservation throughout his tenure. He recognized early on that Mount Auburn’s past approach of simply focusing on routine maintenance was not sufficient for the specialized needs of our collections. With that in mind, he worked to establish new policies that made preservation an essential part of the Cemetery’s mission, and increased the professionalism of the staff – as well as the budget – in the preservation department. His contributions continue to be felt throughout our landscape today.

Your gift to the William C. Clendaniel Preservation Fund gives our staff the resources they need to care for this vital collection for generations to come.

Our skilled preservation staff re-set, wash, repair, and repoint thousands of monuments and fences.

Our Curator of Historical Collections & Archives researches, provides documentation, and recommends preservation priorities.

Consulting sculpture conservators offer advanced expertise to preserve some of our most significant monuments.

Make a Gift Today!

Learn more about recent preservation highlights.

Gardner Mausoleum, 2017 – 2020

Learn more about Bill’s tenure at Mount Auburn.

The Genesis of The Experimental Garden at Mount Auburn Cemetery

Mount Auburn was born from the marriage of two ideas: an ornamental cemetery for the commemoration of the dead and an experimental garden in which to practice the art and science of horticulture.[1] The Cemetery’s founders were members of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, established in 1829. The Garden and Cemetery Committee, formed by the Society to investigate the creation of a garden and cemetery, made critical decisions in the initial design and development of Mount Auburn. Early records referred to the site as “the Experimental Garden and Cemetery of Mount Auburn.” Although the Experimental Garden represents a short-lived chapter in the history of Mount Auburn, it has had an enduring influence on the practice of horticulture and innovation throughout the Cemetery’s history.

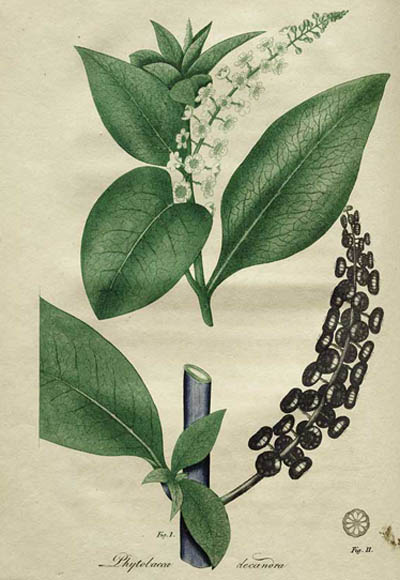

Mid-nineteenth century New England was experiencing a revival of interest in the cultivation of gardens. [2] Although Boston was becoming increasingly populated, the adjacent areas were still rural in character and home to a number of large country estates. The statesman Henry A. S. Dearborn, for example, founder and first president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and enthusiastic advocate for the development of an experimental garden and cemetery, owned a country estate in Roxbury, where he practiced horticulture. Jacob Bigelow, a physician at Harvard Medical School and another principal founder of Mount Auburn, had an ardent interest in botany. His books include Florula Bostoniensis. a Collection of Plants of Boston and Its Vicinity, a valuable manual on plants in the area, and American Medical Botany, with botanical illustrations by Bigelow.

“The core of supporters . . . for a rural cemetery and experimental garden were all people with a shared passion for science and a robust intellectual vigor,” writes Dennis Collins, Horticultural Curator of Mount Auburn.[3] The Horticultural Society’s members included statesmen, industrialists, merchants, lawyers, and doctors representing the Boston elite as well as practicing horticulturalists including botanists, farmers, gardeners, nursery owners, and seed traders.

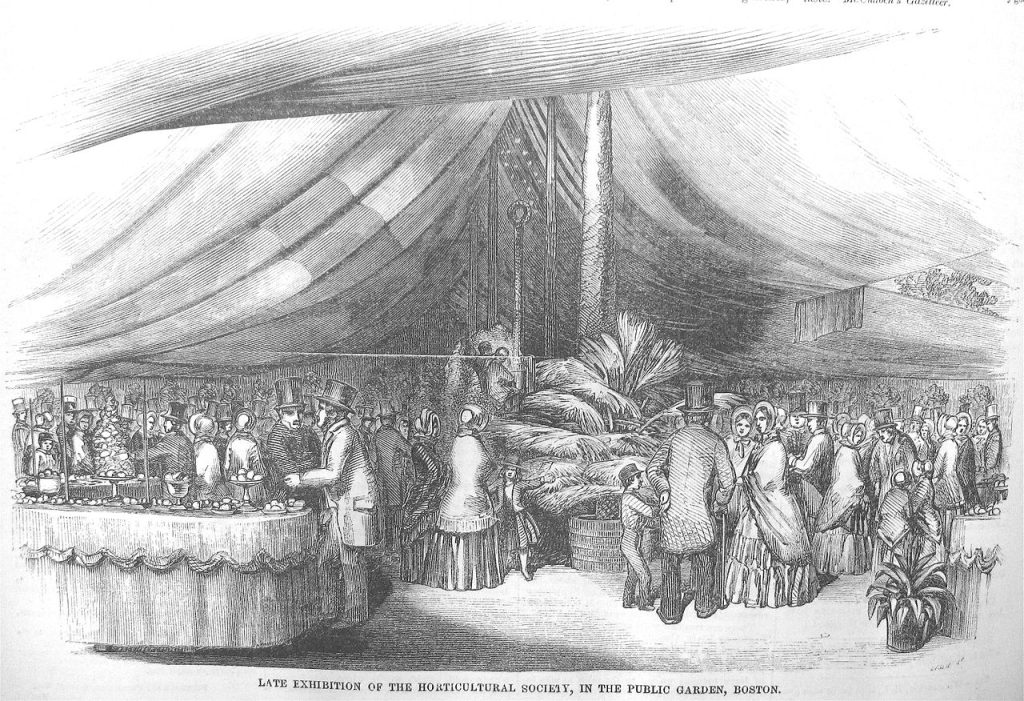

The Society modeled itself after the Horticultural Society of London founded in 1804 (later the Royal Horticultural Society). Members of the Massachusetts society admired other “experimental gardens” and “experimentalists” in France and England, with whom they corresponded. [4] “By emulating their zeal, intelligence, and experimental industry,” the Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society noted, “ . . . we must develop the resources of our own country, which offers such an extensive, interesting, and prolific field of research to the adventurous naturalist.”[5] The Society’s activities included the exchange of books, seeds, and plants; the building of a library with volumes on English and French horticulture; the exhibition of fruits, flowers, and vegetables; and the dissemination of information through meetings, scientific papers, and publications such as the New England Farmer. Dearborn even contemplated building a Botanical Garden and an Institution for Education of Scientific and Practical Gardeners. “An interest has been excited,” Dearborn wrote, “and a spirit of inquiry awakened, auspicious to the institution, while a powerful impulse has been given to all branches of rural industry, far beyond our most sanguine hopes.”[6]

The Society laid out its vision for the Experimental Garden at Mount Auburn:

The objects which will chiefly claim attention, are the collection and cultivation of common, improved, and new varieties of the different kinds of Fruits, Esculent Vegetables, Forest and Ornamental Trees and Shrubs, Flowering, Economical, and other interesting Plants . . . paying particular attention to the qualities and habits of each; instituting comparative experiments, on the modes of culture, to which they are usually subjected, so as to attain a knowledge of the most useful, rare, and beautiful species; —the best process of rearing and propagating them by seeds, scions, buds, suckers, layers, and cuttings;—the most successful methods of insuring perfect and abundant crops, as well as satisfactory results, in all the branches of useful and ornamental planting appertaining to horticulture.[7]

The Society considered the establishment of the Experimental Garden “indispensable to the full development of [its] purposes,” and believed the combination of the Garden and Cemetery would “assist in improving the taste of the public in this highest branch of the art of horticulture.”[8] As visitors to Mount Auburn would come to know about the lives of those in the young country commemorated in the Cemetery, they would also learn about the art and science of horticulture. The combination of an Experimental Garden and Cemetery would promote the Society’s ideas about the moral and purifying aspects of horticulture as well. Zebedee Cook, Jr., vice president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, wrote that in the new site “Nature [would open] a never-failing paradise to those who are content to be innocent and well-employed” and the soul would be “subdued, and the affections purified and exalted.”[9]

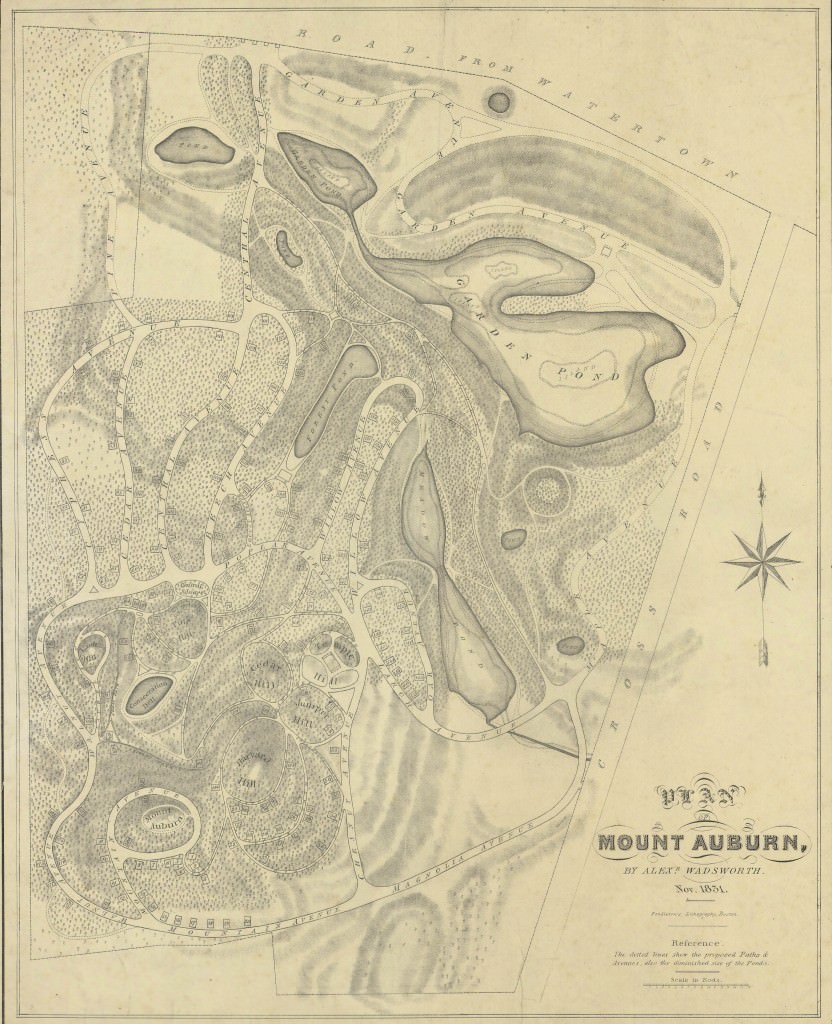

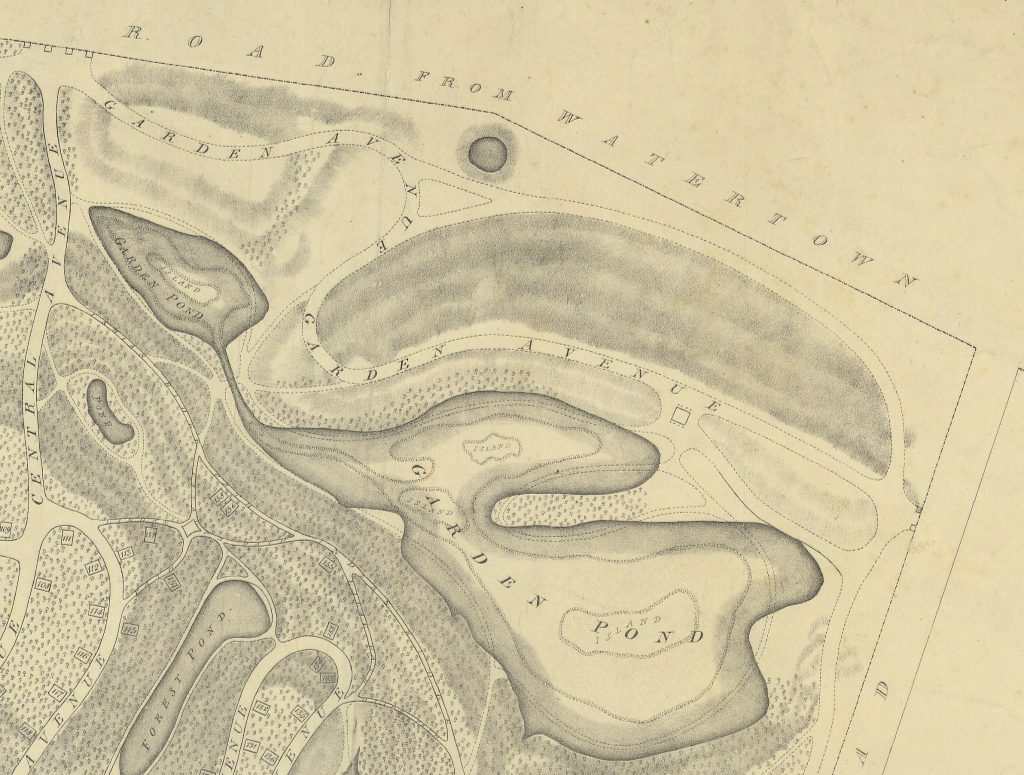

When Massachusetts Horticultural Society purchased 72 acres of land for Mount Auburn in 1831, they set aside 32 acres for the Experimental Garden. The Garden and Cemetery Committee placed the Garden in the northeastern section of the Cemetery, east of Central Avenue near the largest of the ponds, Garden Pond (known today as Halcyon Lake). The area, where the Trustees stipulated no lots would be sold, also afforded a buffer between the public road and burial lots. Dearborn planned for the ornamental grounds of both the Garden and the Cemetery to be “blended, and the walks so intercommunicate as to afford an uninterrupted range over both, as one common domain.”[10]

In 1833, the trustees of Mount Auburn created the position of superintendent and gardener to oversee both the operations of the Cemetery and the cultivation of the Garden. They chose highly skilled horticulturalists for the position. The first superintendent and gardener, David Haggerston, learned the art of horticulture in England from his father.[11] Upon his arrival in Massachusetts, he worked on the estate of Governor Gore in Waltham and then operated a successful nursery in Charlestown known as the Charlestown Vineyard. John Russell became Mount Auburn’s second superintendent and gardener in 1834. Also from England, he worked on the country estate of the Duke of Westminster before coming to Boston, where he found a position with Haggerston at the Charlestown Vineyard. Members of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, both men contributed regularly to horticultural publications such as American Gardener Magazine.

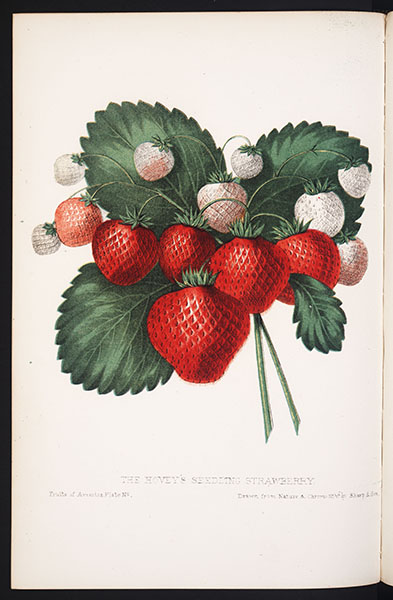

The Experimental Garden provided the Society the opportunity to cultivate and exchange domestic and foreign varieties of fruits, flowers, vegetables, and plants and to conduct horticultural experiments. The Society often received donations of seeds from horticulturalists, botanists, and gardeners around the world, which they distributed among its members. It now entrusted many of these donations to Mount Auburn for use in the Experimental Garden. Haggerston and Russell also exhibited vegetables, fruits, and flowers from the Garden in the Massachusetts Horticultural Society exhibition halls.[12] These weekly exhibits, open to the public, provided an educational opportunity to share horticultural techniques and innovations, and the Society awarded prizes to the best species and exhibits.

As Dearborn reported:

I am happy to announce to the Society that the plan of the experimental garden at Mount Auburn is in progress, and will soon be carried completely to effect. Mr. Haggerston, the gardener, moved into the cottage early last month, and with two laborers, has been constantly and industriously employed in setting out over one thousand and three hundred forest, ornamental, and fruit trees, planting culinary vegetables, and preparing hotbeds for receiving a great variety of useful plants, which are intended to be distributed over the various compartments of the garden, and on the borders of the avenues and paths. Among the seeds planted are four hundred and fifty varieties which have been sent to the society from Europe, Asia, and South America.[13]

Soil from the clearing of the ponds was added to the Garden to make the area more suitable for the cultivation of trees and shrubs. Haggerston and Russell grew flowering plants for use as ornamentation of the grounds and along the avenues and path, to which Bigelow assigned botanical names. The Cemetery kept a record of all seeds, plants, and trees received, their species, and from whom and where they came as well as “all monies produced by the sale of flowers, plants, shrubs, and trees from the said Garden.” [14] Among the plants cultivated were magnolias, petunias, delphiniums, asters, radish, cauliflower, broccoli, peas, beans, melons, and strawberries. Dennis Collins explains, “The most exotic source might have been the Botanical Society of the Kingdom of Naples, and perhaps one of the more recognizable exotic plants was the Guul ibrischim or ‘silk tassel rose’ sent from Turkey.”[15] While members of the Garden and Cemetery Committee championed the exchange of plants with other countries, they also saw the role of the Experimental Garden in helping to develop “the vast vegetable resources of the Union,―give activity to enterprise,―increase the enjoyment of all classes of citizens,―advance the prosperity, and improve the general aspect of the whole country.”[16]

By September 1834, Mount Auburn had sold 351 lots, and proceeds from the sales helped cover the expenses of the Garden and the Cemetery. Proprietors of burial lots automatically received a lifetime membership in the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and a controlling vote in the Society’s affairs.[17] As the number of lot owners increased, differing priorities arose over the expense of maintaining both the Cemetery and the Garden.[18] The History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society observed that many lot owners may have felt “an indifference, if not a positive aversion, to the idea of an experimental garden.”[19]

In 1834, the Cemetery established a committee to investigate how “to render the garden productive and profitable.” [20] Mount Auburn trustees Joseph P. Bradlee and Elijah Vose, who was vice-president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and later president, submitted a detailed report on the state of the Garden. They offered strategies for making the Garden self-sustainable and profitable with the idea “to advance by degrees, with small expenditures, until it shall be made capable of furnishing not only all the trees, shrubs . . . wanted for the purposes of the Garden and Cemetery, but its surplus products be equivalent . . . to defraying the expenses of the labor of conducting it.”[21] They expressed their hope that the Garden be considered “not only an object of interest and of utility but worthy of forming a part of the institution of Mount Auburn.”[22]

Tensions increased, however, over the expenses associated with the garden, and Mount Auburn began to face future capital expenditures, including in the 1840s, the replacement of the perimeter wooden fence with an iron fence and the building of Bigelow Chapel. The History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society noted that the “subject was much discussed both in and out of the meetings of the Society, considerable warmth of feeling being elicited among the friends of the two departments; and it became evident that a peaceful arrangement was not likely to be made, except by a sale of Mount Auburn, by the Horticultural Society, to a new corporation, to be composed of owners of the holders of lots.”[23] Joseph Story, Mount Auburn’s first president and an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, presided over a committee to dispose of the interests of the Society.

In June 1835, the Proprietors of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn, a newly established entity, took over ownership of the Cemetery from the Society, and Mount Auburn no longer maintained the Garden.[24] From 1835 until 1976, a percentage of funds from the sale of lots went to the Horticultural Society.[25]

“By putting the grave in the garden, Mount Auburn transformed American burial practices,” notes Meg Winslow, Curator of Historical Collections & Archives at Mount Auburn.[26] While the Experimental Garden did not endure, the union of commemoration and horticulture manifested in a new America landscape. Collins explains that, “Each of the generations of horticulturalists, who have been the stewards of this landscape . . . has brought its own vision and innovative spirit to the task of building and improving Mount Auburn.”[27] From the creation of 19th-century greenhouses to 21st-century climate action and sustainability programs, the Cemetery has remained dedicated to the advancement of the art and science of horticulture—as eloquently articulated in the founders’ vision of the Experimental Garden.[28]

[1] “An Act to Incorporate the Proprietors of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn,” 1831, p. 6. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-005-001/display/1061993.

[2] See Mary-Alice Rea, “Introduction of Economic Plants into New England,” Economic Botany, vol. 29, no. 4 (Oct. -Dec .1975), pp. 333-356.

[3] Dennis Collins, “A History of Horticultural Innovation,” Sweet Auburn (Fall 2010), p. 1.

[4] Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1838 (Boston: William D. Ticknor, 1847), p. 21.

[5] Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1838, p. 21.

[6] Henry A. S. Dearborn in Robert Manning, History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1878 (Boston: Rand, Avery, for the Society, 1880), p. 68.

[7] Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, p. 64.

[8] Manning, p. 76.

[9] Zebedee Cook Jr., An Address Before the Massachusetts Horticultural Society in Commemoration of Its Second Annual Festival, the 10th of Sept., 1830 (Boston: Isaac R. Butts, 1830), pp. 27- 28.

[10] Manning, p. 96.

[11] Haggerston left Mount Auburn in 1834 to work on the vast estate of John Perkins Cushing in Belmont.

[12] “Obituary, Death of David Haggerston,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, vol. 1863.

[13] Dearborn in Manning, p. 98.

[14] “Massachusetts Horticultural Society Contract with James W. Russell, 1834, p. 1. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1834-feb-06-contract-mhs-russell-jw-gardener/display/1218029.

[15] The silk tassel rose is known today as “mimosa” (Albiizia julibrissin). Collins, p. 2.

[16] “An Account of the Proceedings, In Relation to the Experimental Garden and the Cemetery of Mount Auburn,” Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1838, p. 65.

[17] “An Act to Incorporate the Proprietors of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn,” 1831, p. 5. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-005-001/display/1061993.

[18] Manning, p. 107.

[19] Manning, pp. 101-102.

[20] “Records of Committees,” Aug. 30, 1834, p. 23 and October 27, 1834, p. 24. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-003-001/display/1217964.

[21] “Report on the Committee to Examine the Garden,” 1834, pp. 6-7. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-034-010/display/1218015.

[22] “Report on the Committee to Examine the Garden,” 1834, p.7. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-034-010/display/1218016.

[23] History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1878, p. 110.

[24] Proprietors of new lots no longer received lifelong membership in the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, unless they applied individually to the Society. The Society gave the Proprietors of the Cemetery use of a room in one of its Horticultural Halls or its library for annual meetings. “Massachusetts Horticultural Society Agreement,” October 9, 1835. https://fromthepage.com/mountauburncemetery/mount-auburn-cemetery/1831-015-039/display/32046353.

[25] In 1834, Henry A. S. Dearborn, resigned as president of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society. He went on to design Forest Hills Cemetery in Roxbury, where he was elected major. In later years, Bigelow, who served as second president of Mount Auburn from 1845 to 1871, distanced himself from association with the experimental garden.

[26] Personal communication, Meg Winslow, 3/15/22.

[27] Collins, p. 1.

[28] In 2010, Mount Auburn staff created another Experimental Garden, known as the E-Garden, for the testing of new products, techniques, and plants for future use on the grounds.