The Cemetery in Three-Dimension: Mount Auburn’s Nineteenth-Century Stereographs

Of all the early photographic formats, nothing transports the viewer back in time like nineteenth-century stereoviews. Stereoviews consisted of two photographs of an identical subject affixed side by side. When looked at through a device known as a stereoscope, they gave the illusion of a three-dimensional scene.

The system worked on the principle of binocular vision as described by British scientist Charles Wheatstone in 1838. Wheatstone understood that human depth perception is created by the left and right eye perceiving slightly different views that the brain converges together as a three-dimensional image. Stereoviews were often created with a twin-lens camera that took exposures around two inches apart to replicate the approximate distance between the eyes. Wheatstone observed that viewing a stereo pair of images through a stereoscope, with each eye looking at a single image, rendered a three-dimensional view.

Stereoscope, H. C. White Co.

In 1849, British inventor Charles Brewster improved on Wheatstone’s mirror and prism stereoscope, with a smaller, lenticular device in which each eye viewed one of a stereo pair of images through a separate lens. In 1859, physician and photograph enthusiast Oliver Wendell Holmes, who is buried at Mount Auburn, invented an inexpensive, hand-held stereoscope that allowed the distance from the lens to the stereoview to be adjusted. Blinders on the sides of the stereoscope reduced the interference of peripheral views and light. Companies such as H. C. White Company prided themselves on the production of both stereoscopes and stereoviews. Mount Auburn’s Historical Collections & Archives houses a stereoscope by H. C. White as well as a captivating collection of more than four hundred stereoviews of the Cemetery, a collection that continues to grow through new acquisitions.

From the 1850s to the 1890s, stereoviews were typically produced as albumen prints made from glass-plate negatives. Usually adhered to card mounts, these stereo prints were referred to as both stereoviews or more specifically as stereographs. The mounts came in a range of colors from muted gray to vivid orange, and the prints were sometimes hand-colored through the application of paint. Multiple prints could be made from a single glass-plate negative, and stereo publishers produced and distributed millions of stereographs in the U.S. and abroad. Considered the educational and entertainment technology of its time, stereographs adorned classrooms and most household parlors. This popular and affordable cultural fixture offered three-dimensional views of noteworthy sites and subjects around the world, including Mount Auburn, which by the mid-eighteen hundreds had grown into an international tourist destination.

Asa Gray Garden.

Well-known publishers such as George W. Griffith and Appleton & Co. created their own images and imported those of others. Stereographs were sold through mail order, magazine advertisements, door to door salesmen, or in bookstores, stationery stores, and pharmacies. Some came in boxed sets. Stereograph card mounts often noted the name of the photographer, distributor, and publisher as well as other subjects offered by the publisher. On the back of some Mount Auburn stereographs, publishers included information about the history of the Cemetery as well as lists of additional views of Mount Auburn’s monuments, landmarks, and scenic vistas, for purchase.

Verso of two stereoviews.

In a series of articles on photography for the Atlantic Monthly, Olivier Wendell Holmes enthused that the effect of the stereoscope “is so heightened as to produce an appearance of reality which cheats the senses with its seeming truth.”[1] Photographers learned that composing stereo images with a variation of distance among objects produced an even greater three-dimensional effect by simulating the relative spatial distance of figures to one another. Viewers also experienced photographic compositions with distinct foreground and background areas as layered planes. In one Mount Auburn stereograph, tombs and memorials emerge in an almost tangible relief form against the backdrop of Washington Tower perched on the Cemetery’s highest summit. In a view of Auburn Lake, trees in the foreground give the illusion of being surrounded by space, and the eye is drawn to the second basin of the lake receding into the background.

View towards Washington Tower. Auburn Lake.

Other stereographs of the Cemetery allow us to experience a kind of virtual reality of people in the landscape a century and a half ago—such as a group gathered around the Harnden monument or a soldier standing in front of the Sphinx. In a stereograph of Asa Gray Garden, two women with parasols take a stroll as a nearby gardener tends to the lawn. Bigelow Chapel appears like an apparition above the trees in the distance.

Harnden Monument. Sphinx and soldier. Asa Gray Garden

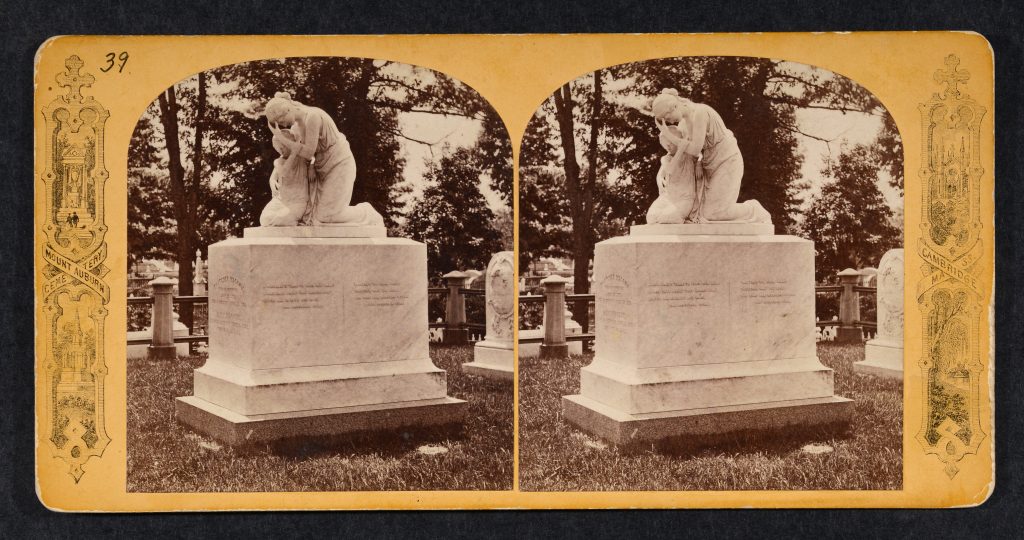

Mount Auburn’s collection also provides three-dimensional evidence of characteristics of the landscape that have altered over time: the dirt road of Mount Auburn Street in front of the Egyptian Gateway entrance or the view from Washington Tower that shows the beginnings of development along the Charles River. The stereograph of the Thatcher Magoun monument reveals the original details of the face and hand of the poignant mourning figure that have since eroded.

Entrance Gateway. View of Charles River from Washington Tower. Magoun Monument.

“It is easily forgotten now how pervasive was the experience of the stereoscope and how for decades it defined a major mode of experiencing photographically produced images,” Jonathan Crary writes in Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century.[2] Whether an armchair traveler from the nineteenth-century or collector of today, one appreciates the magical, heightened perception of being in the scene. We become immersed in the recesses of the cavernous space of Consecration Dell, the flight of the ascending spirit in Thomas Crawford’s monument to Amos Binney, or the intensity of the dense crowds outside Bigelow Chapel on Decoration Day—a sensation Holmes described as “the mind feel[ing] its way into the very depths of the picture. ”[3]

Consecration Dell. Amos Binney Monument. Bigelow Chapel, Decoration Day.

Interested in learning more? You can browse Mount Auburn’s collection of stereoviews in our online database at: https://mountauburn.pastperfectonline.com

1. Oliver Wendell Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” Atlantic Monthly, June 1859.

2. Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer: On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1990), 117-118.

3. Holmes, “The Stereoscope and the Stereograph,” Atlantic Monthly, June 1859.

Comments are closed.