Stones from the Homestead

by Mount Auburn Docent Robin Hazard Ray

In English, “rock” is geochemical material that lies in its natural state; it becomes “stone” when a human chooses, moves, or changes it. This distinction is found in every European language: roche and pierre in French, roccia and pietro in Italian, Fels and Stein in German. Cemeteries are of course full of stones that have been lovingly and often artistically shaped to commemorate the dead. But there are a few at Mount Auburn whose significance lies in the rock from which the stone was made.

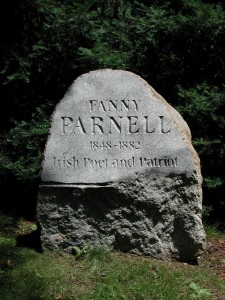

Fanny Parnell Monument,

Lot 167 Violet Path. Wicklow Granite.

The Parnell family were landowners with an estate in Avondale, County Wicklow, Ireland. Despite membership in the Anglo-Irish Protestant ruling class, Charles Stewart Parnell (1846–1891) and his sister Fanny Parnell (1848–1882) became fervent Irish nationalists, campaigning for economic justice and Home Rule. Fanny’s poem “Hold the Harvest,” published in 1880, was widely reprinted in the Irish press and became the unofficial anthem of the Irish national cause.

Fanny died suddenly at age 33 while in the United States raising funds for the Irish cause, and it was decided to bury her at Mount Auburn with her mother’s kin, the Tudor family. (Frederick Tudor, known locally as “the Ice King,” made a fortune selling ice from Fresh Pond; his sister was Fanny’s grandmother.) Fanny’s magnificent funeral cortege, drawn by six white horses, drew crowds of mourners as it traveled through Philadelphia, New York, and Boston. The burial took place at Mount Auburn on 19 October 1882, but, perhaps fearing that her remains would be trifled with by political enemies, her grave bore no marker.

Nine years later, Charles Parnell died in Ireland. He was buried in Dublin’s famed Glasnevin Cemetery atop a mass grave of cholera victims—a sure-fire means of discouraging desecration. Marking his grave is an immense boulder of Wicklow Granite, the rock that underlies the Parnell home in Avondale, marked simply “PARNELL”.

The Wicklow granite is distinctive in having tiny garnets in its matrix. The garnets are easy to spot because they are red and grow in a dodecahedral shape. Garnet is a metamorphic mineral, X3Y2(SiO4), where X and Y may be iron, magnesium, manganese, or calcium and Y may be aluminum, chromium, iron, even titanium; the ones here are probably almandine, Fe3Al2Si3O12. The presence of garnets suggests that when the Wicklow Granite melt was making its way to the surface, it swallowed and mostly digested a metamorphic host-rock—a schist—already endowed with garnets.

In the late twentieth century, the Parnell Society of Ireland became aware that no memorial had ever been erected at Fanny’s grave. They commissioned a marker for Fanny to be made from a boulder of Wicklow Granite, echoing Charles Parnell’s monument in Dublin and evoking the very bedrock of Ireland. This stone, complete with tiny garnets, was installed at Mount Auburn in 2000. The boulder brings a bit of Fanny’s beloved Ireland to her resting place.

Gustavus A. Jasper Monument,

Lot 3913 Fern Path. Roxbury “Puddingstone” Conglomerate.

Gustavus A. Jasper (1834–1884) had “made good.” Born in Bremen, Germany, in 1834, Jasper had immigrated to the United States as a youth and eventually rose to become director of the Standard Sugar Company, a refinery located on the Fort Point Channel. In 1869, he was granted a U.S. patent for an “Apparatus for Drying Sugar and Other Like Articles,” which may or may not have contributed to his prosperity.

Jasper and his family had led an itinerant life, living now in a Boston hotel, now in Charlestown, before settling on Bowdoin Street in Dorchester. They were living there, amid outcrops and informal quarries of Roxbury Puddingstone, when Gustavus met his death at age 50.

The Puddingstone is very distinctive. It is an ancient conglomerate (more than 600 million years old) consisting of rounded cobbles and pebbles of various rock types roughly glued together with a cement of gray-green mud. The Puddingstone crops out naturally in southern parts of the Boston Basin: Roxbury, Dorchester, Brookline, and as far south as Milton. It was extensively quarried for use in architectural foundations and facing stones and became a recognizable symbol of Boston itself. In 1886, a 20-ton monument made of Puddingstone was erected at Gettysburg to honor the 20th Massachusetts Infantry—the “Harvard Regiment”—which played a crucial role in Pickett’s Charge on July 2, 1863. Roxbury Puddingstone was designated the Massachusetts state rock in 1983.

It was perhaps with this symbolism in mind that the family of Gustavus’s daughter Fannie Jasper Dodd (1870–1915) commissioned a boulder of Puddingstone to mark the family grave at Mount Auburn. The Jasper family may have had roots in Germany, but it was now anchored in the bedrock of Boston.

Louis Agassiz Monument,

Lot 2640 Bellwort Path, Central Aar Granite.

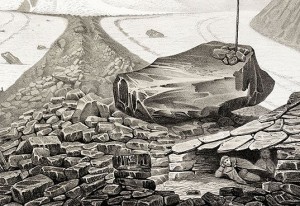

When Louis Agassiz (1807–1873) died at the age of 66, he was a long way from home. Born the son of a clergyman in the French-Swiss town of Môtier, he made a dramatic impact on geological science in his native Switzerland by assembling evidence for and naming the “Ice Age”: a period between 2 million and 15,000 years ago when glaciers blanketed much of the Northern hemisphere, leaving behind a landscape of scarred, polished, and ground-up rocks. He conducted firsthand research on the Aar Glacier in southern Switzerland, measuring the flow of the ice rivers and illustrating their effects on the local bedrock, the Central Aar granite. Lithographs in his beautiful tome Études sur les Glaciers (1840) show blocks of such stone—called “erratics” or Findlinge (lost children)—riding along a conveyor belt of ice toward their deposition in a remote moraine.

The Central Aar granite is a coarse-grained, calcium-rich granite of Permian-Mesozoic age. It shouldered its way to the earth’s surface as the Alps were being formed. (The African tectonic plate has been in a long slow collision with the European tectonic plate, piling northern Italy up against what is now France, Switzerland, and Austria and spawning volcanoes along Italy’s western edge.) The granite was lightly metamorphosed in a second phase of its development (alpine greenschist metamorphosis), creating quartz veins and a foliated texture—that is, the alignment of minerals along parallel planes. We can see in the Études sur les Glaciers lithographs that the Aar granite breaks apart in geometric, almost trapezoidal forms under the pressure of the glacial ice.

Agassiz found the Americas a greater arena for his scientific career than provincial Switzerland, and he moved here in 1846. He settled at Harvard and became a great popularizer of science at a time when science was regarded with suspicion by many American Christians. His scientific views, though embraced by an adoring public, were often characterized by inflexible convictions that could not be interrogated by experiment. As the years went on, he became an object of scorn and exasperation among fellow scientists such as Charles Darwin and botanist Asa Gray.

For the most part Agassiz snubbed his home country and expressed little interest in returning even to visit. But when he died, his son Alexander reached back to his father’s origins in Switzerland and in geology for a proper memorial. He contacted a cousin in the old country who selected a massive trapezoidal block of the Central Aar granite, whose smooth, foliated surfaces are ideal for inscription. The 2,500-pound Findling stone was shipped to the United States, “rough as it came from the Glacier, untouched by the hand of the Stone-Cutter,” requiring only the lettering to be added. As Agassiz’s biographer Christoph Irmscher notes, the monument is fitting for Agassiz in more ways than one. First, Agassiz was himself a Findling in America. Second, Irmscher writes, “Although lifeless itself, Agassiz’s boulder . . . captures the irony that lies behind Agassiz’s science itself: the assumption, presented as a certainty, that in nature all living things stay as they are had been developed by a scientist who had not stayed where he was.”

Leave a Reply