Western redcedar, Thuja plicata

In a vast, Northwest forest,

Where snow falls, upon cedars:

As though in answer to an unspoken chorus,

Mine eyes rise to meet with hers…

-Maurice Harris

Previously we discussed Alaska yellow-cedar, Xanthocyparis nootkatensis. It is apropos to follow up with Western redcedar, Thuja plicata, as these two conifer cousins are within the same family, CUPRESSACEAE, the cypress family, and often occupy the same native ranges. Western redcedar are found growing at sea level to 4500’ from Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and California, also eastward at higher elevations (to 6500’) of Alberta, Montana and Idaho but with diminished growth in areas lacking moisture. It has been called numerous additional common names: giant arborvitae, Pacific red cedar, giant cedar, British Columbia cedar and canoe cedar. In spite of these names, it is not a true cedar, within the genus Cedrus, which we also have previously profiled.

Previously we discussed Alaska yellow-cedar, Xanthocyparis nootkatensis. It is apropos to follow up with Western redcedar, Thuja plicata, as these two conifer cousins are within the same family, CUPRESSACEAE, the cypress family, and often occupy the same native ranges. Western redcedar are found growing at sea level to 4500’ from Alaska, British Columbia, Washington, Oregon and California, also eastward at higher elevations (to 6500’) of Alberta, Montana and Idaho but with diminished growth in areas lacking moisture. It has been called numerous additional common names: giant arborvitae, Pacific red cedar, giant cedar, British Columbia cedar and canoe cedar. In spite of these names, it is not a true cedar, within the genus Cedrus, which we also have previously profiled.

Nonetheless Hilary Stewart’s authoritative book, Cedar: Tree of Life to the Northwest Coast Indians lavishly recounts the historic, cultural importance of Western redcedar. Here is one example, ”…Throughout her life the newborn baby girl…would rely on the magnificent cedar as an integral part of her life … it provided the necessities …A large canoe would carry her entire family out to their summer village on the outer coast to fish for salmon and gather other resources that would see them through the winter. Without the nets, traps, weirs and harpoons, all made of cedar, to harvest the salmon, and the large cedar wood boxes or root baskets in which to store foods for the long winter, her family would have found it difficult to survive. Practical clothing on the raincoast came from the cedar, as did large structures to house and shelter extended families from the storms of winter and rains of spring. When people died, their remains were wrapped in cedar bark mats, put in cedar burial boxes…From birth to death, the wood, bark, roots, withes and leaves of the mystical, powerful cedar tree provided generously for the needs of the people of the Northwest Coast – materially, ceremonially and medicinally.”

Erna Gunther’s classic Ethnobotany of Western Washington enumerated further uses specific to differing northwest coast nations. Medicinally: chew the buds and swallow for sore lungs, chew buds for toothache, boil them for a gargle, boil the ends of leaves for coughs…a cold medicine, seeds are steeped with the ends of limbs to break a fever. Materially: house planks, house posts, roof boards, boxes, spindle for spinning, herring rake, dugout canoes, totem poles, the fine shredded bark for padding in infants’ cradles, sanitary pads, towels, a coarser grade of bark for skirts, dresses, capes and rainhats. Limbs stripped, soaked and twisted into ropes, even heavy enough to tow home dead whales.

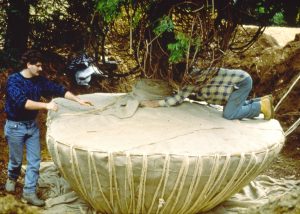

The whales noted above were successfully hunted by ocean-going people such as the Haida in canoes made from single Western redcedar logs skillfully hollowed and shaped. Stewart describes thus, ”Nowhere else in the world was a dugout developed to such a degree of sophistication; no other people had a dugout that could match the speed, capacity and seaworthiness…The earliest Europeans to visit the coast… marveled…on the west coast of Vancouver Island, Captain James Cook estimated that 500 people occupied the 80 canoes that swarmed around his vessel for trading…” Cook reported that the average canoe was 40-feet-long. Stewart also quotes a missionary, Rev. Charles Moser, who had a chance to watch canoes being made, “All the work is done without instruments to go by or measure; yet most of these Indian canoes are so true that not even an expert could detect the least flaw or imperfection.” Fortunately, one of these larger Haida canoes, 64-feet-long, is now housed as a permanent exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

The whales noted above were successfully hunted by ocean-going people such as the Haida in canoes made from single Western redcedar logs skillfully hollowed and shaped. Stewart describes thus, ”Nowhere else in the world was a dugout developed to such a degree of sophistication; no other people had a dugout that could match the speed, capacity and seaworthiness…The earliest Europeans to visit the coast… marveled…on the west coast of Vancouver Island, Captain James Cook estimated that 500 people occupied the 80 canoes that swarmed around his vessel for trading…” Cook reported that the average canoe was 40-feet-long. Stewart also quotes a missionary, Rev. Charles Moser, who had a chance to watch canoes being made, “All the work is done without instruments to go by or measure; yet most of these Indian canoes are so true that not even an expert could detect the least flaw or imperfection.” Fortunately, one of these larger Haida canoes, 64-feet-long, is now housed as a permanent exhibit at the American Museum of Natural History in New York.

Bill Read wrote in his foreword to Stewart’s comprehensive book, “…Huge, some of these cedars, five hundred years of slow growth, towering from their massive bases. The wood is soft, but of a wonderful firmness and, in a good tree, so straight-grained it will split true and clean into forty-foot planks, four inches thick and three feet wide, with scarcely a knot…When steamed it will bend without breaking. It will make houses and boats and cooking pots. Its bark will make mats, even clothing…”

Where the cedars are, you will find me,

Reclined against a sturdy, ancient trunk…

-Michael Walker

These lustrous, evergreen trees make noble specimens reaching 50 to 80-feet in height in eastern landscape usage although the current tallest one known, the Willaby Creek tree, near Lake Quinault, in Olympic National Forest, is 195-feet tall. The rich-green, foliage is composed of ¼-inch-long, scale-like leaves in overlapping, opposite pairs, with each successive pair at 90-degrees to each other. The dense, flat sprays of leaves create branchlets evocatively described by Michael Dirr in his Dirr’s Hardy Trees and Shrubs as “…elegantly postured, like a lady’s hand outstretched for a kiss.” The leaves have a distinct, pleasant scent when bruised or crushed, some referring to it as tansy-like, while others have suggested a pineapple aroma.

As with many conifers, separate, small, inconspicuous male and female flowers are produced on each Western redcedar tree in the spring. When successfully fertilized the female flowers may produce ½-inch-long cones, often in upright clusters on the branches. Initially green, but maturing to a tan/brown color, each cone consists of four pairs of overlapping, elongate scales, shaped like tiny rowboats. Eight to fourteen tiny, 1/16-inch, winged seeds are aerially wind dispersed, as they have been for ten-plus millennia. The Gymnosperm Database documents a Thuja plicata in Olympic National Forest that was cored and provided a ring count of 1460 years. Another tree was aged at 1212 years in Pacific Rim National Park, British Columbia.

As with many conifers, separate, small, inconspicuous male and female flowers are produced on each Western redcedar tree in the spring. When successfully fertilized the female flowers may produce ½-inch-long cones, often in upright clusters on the branches. Initially green, but maturing to a tan/brown color, each cone consists of four pairs of overlapping, elongate scales, shaped like tiny rowboats. Eight to fourteen tiny, 1/16-inch, winged seeds are aerially wind dispersed, as they have been for ten-plus millennia. The Gymnosperm Database documents a Thuja plicata in Olympic National Forest that was cored and provided a ring count of 1460 years. Another tree was aged at 1212 years in Pacific Rim National Park, British Columbia.

Love is a seed

But like that of a cedar…

It may live for a thousand year…

-Wael Karaameh

Talking in terms of a thousand years brings us to anthropologist, ethnobotanist, Wade Davis who’s Shadows in the Sun: Travels to Landscapes of Spirit and Desire includes a chapter titled “In the Shadow of Red Cedar.” Here is an excerpted sampling, ”…coastal temperate rainforests of North America…Around ten thousand years ago…red cedar remained rare…gradually…expanded their hold… the diffusion of red cedar that allowed the great cultures of the Pacific northwest to emerge…specialized tools first appear…around 3000 B.C., roughly the period when red cedar came into its present dominance in the forests…Large cedar structures were in use a thousand years before the Christian era…”Other historic specificity of red cedar forest dominance and human cultural use includes George MacDonald, former West Coast Archaeologist at the National Museum of Canada who with Richard Inglis published “An Overview of the North Coast Prehistory Project (1966-1980)” in British Columbia Studies that included analysis of wood artifacts, nearly 2000 years old, recovered from the waterlogged Lachane site. From 322 samples, twelve species were botanically identified. In order of abundance they were red cedar (37%), western fir (26%), western hemlock (17%), yellow cedar (8%), yew (2%), spruce (2%), birch (2%), juniper, alder and pine (1% each), and crabapple and maple.

Talking in terms of a thousand years brings us to anthropologist, ethnobotanist, Wade Davis who’s Shadows in the Sun: Travels to Landscapes of Spirit and Desire includes a chapter titled “In the Shadow of Red Cedar.” Here is an excerpted sampling, ”…coastal temperate rainforests of North America…Around ten thousand years ago…red cedar remained rare…gradually…expanded their hold… the diffusion of red cedar that allowed the great cultures of the Pacific northwest to emerge…specialized tools first appear…around 3000 B.C., roughly the period when red cedar came into its present dominance in the forests…Large cedar structures were in use a thousand years before the Christian era…”Other historic specificity of red cedar forest dominance and human cultural use includes George MacDonald, former West Coast Archaeologist at the National Museum of Canada who with Richard Inglis published “An Overview of the North Coast Prehistory Project (1966-1980)” in British Columbia Studies that included analysis of wood artifacts, nearly 2000 years old, recovered from the waterlogged Lachane site. From 322 samples, twelve species were botanically identified. In order of abundance they were red cedar (37%), western fir (26%), western hemlock (17%), yellow cedar (8%), yew (2%), spruce (2%), birch (2%), juniper, alder and pine (1% each), and crabapple and maple.

More recent historical Western redcedar use would take us to Canoe Camp, a National Park Service site, near Orofino, Idaho. This place memorializes where Meriwether Lewis (1774-1808) and William Clark (1770-1838) and their Corps of Discovery learned from the Nez Perce people in September, 1805 how to use these trees to create five dugout canoes allowing them to travel the Clearwater, Snake and Columbia Rivers to complete their efforts to reach the Pacific Ocean. Botanist and author, Douglas Culross Peattie (1898-1964) in A Natural History of Western Trees partially describes this, “To make the needed pirogue or dugout, such a tree must be of great size, big enough to carry not only men but food, trading goods, and all sorts of equipment. Its wood must be the lightest possible, for buoyancy and ease of portage around the rapids. It must, since they had but simple tools with them, be soft in texture, straight-grained, with easy splitting qualities. And it must not decay in water…the success of the expedition depended on such a tree…So on the twenty-fifth…felled the trees…With fire, mallet and crude chisel, they fashioned four large pirogues and a smaller one, “to spy ahead”… set out upon the last stage of the outward journey, downstream to the Pacific, borne in the great boles of the Giant Canoe Cedar, which lumberman today call the Western Red Cedar.”

More recent historical Western redcedar use would take us to Canoe Camp, a National Park Service site, near Orofino, Idaho. This place memorializes where Meriwether Lewis (1774-1808) and William Clark (1770-1838) and their Corps of Discovery learned from the Nez Perce people in September, 1805 how to use these trees to create five dugout canoes allowing them to travel the Clearwater, Snake and Columbia Rivers to complete their efforts to reach the Pacific Ocean. Botanist and author, Douglas Culross Peattie (1898-1964) in A Natural History of Western Trees partially describes this, “To make the needed pirogue or dugout, such a tree must be of great size, big enough to carry not only men but food, trading goods, and all sorts of equipment. Its wood must be the lightest possible, for buoyancy and ease of portage around the rapids. It must, since they had but simple tools with them, be soft in texture, straight-grained, with easy splitting qualities. And it must not decay in water…the success of the expedition depended on such a tree…So on the twenty-fifth…felled the trees…With fire, mallet and crude chisel, they fashioned four large pirogues and a smaller one, “to spy ahead”… set out upon the last stage of the outward journey, downstream to the Pacific, borne in the great boles of the Giant Canoe Cedar, which lumberman today call the Western Red Cedar.”

We grow about three dozen Western redcedar, Thuja plicata at Mount Auburn. On your next visit look for some of them on Central Avenue, Elm Avenue, Garden Avenue, Birch Avenue, Story Road, Pheasant Path, Vesper Path and Wistaria Path among other locations.

The cedars are silent

The nightingales

have flown…

-Emmanuel George

Leave a Reply to chris Cancel reply