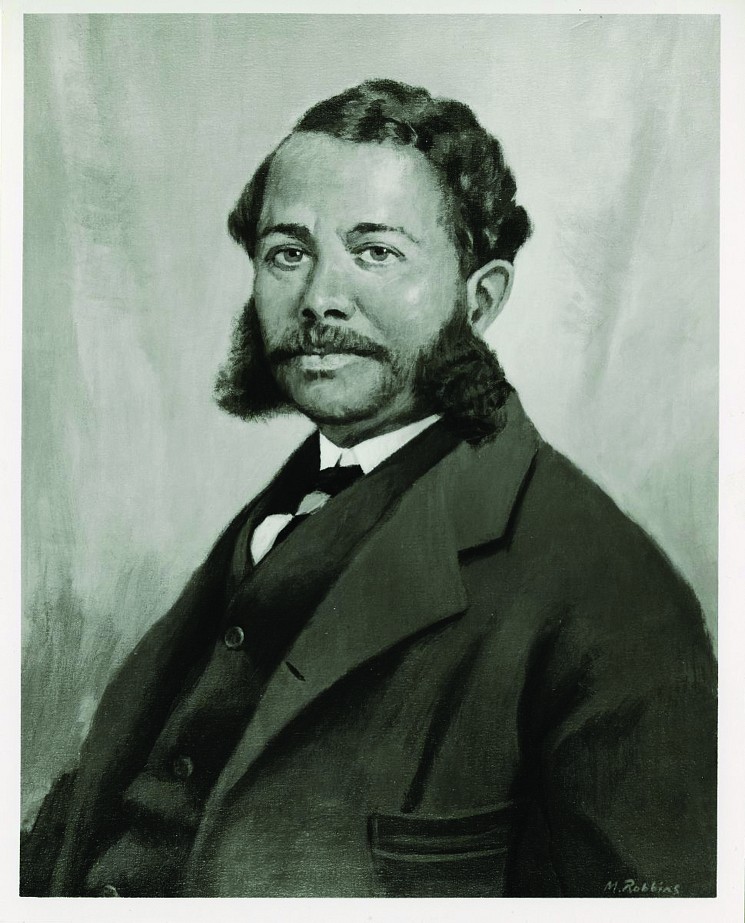

George Lewis Ruffin (1834 – 1886)

Lawyer and Judge

Originally from Virginia, George Ruffin was the eldest son of free Black parents. His family moved to Boston in response to a law that prohibited free Blacks in Virginia from learning to read or write. Ruffin attended Boston public school and found work in a barbershop, often the site of lively political discussions.

In 1858, Ruffin wed Josephine St. Pierre. Throughout their marriage, the Ruffins worked together supporting social causes. The couple moved to Liverpool, England, for six months and returned home on the eve of the Civil War. George and Josephine helped to recruit Blacks in the military and served on Boston’s Sanitary Commission. In Boston they lived on Beacon Hill with many neighbors, White and Black, who shared their abolitionist ideals.

After training as an apprentice in a law office, George was accepted to Harvard Law School in 1868 and became the first African American to graduate, completing the two-year program in only a year. In 1871, Ruffin was elected to the Massachusetts legislature, and he served on the Boston City Council from 1876 to 1877. He worked for the law firm of Harvey Jewell, focused on criminal law, and represented Black and White clients. “In the post-bellum decades, Boston’s Black citizens demanded and won both civil rights legislation and seats in the state legislature,” Stephen Kantrowitz explains in More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889. “They used numbers and moral force to establish themselves as a group to be reckoned with.”[1]

Ruffin wrote an eloquent preface to the autobiography of his friend Frederick Douglass, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. While Ruffin had the benefit of attending Harvard, he admired Douglass for achieving an education through other means. “[Douglass] has surmounted the disadvantage of not having a university education, by application and well-directed effort. He seems to have realized the fact, that . . . it is not positively necessary to go to college, and that information may be had outside of college walks; books may be obtained and read elsewhere,” Ruffin wrote.[2]

In 1883, Ruffin reached another milestone by becoming a judge in the district court of Charlestown, the first African American to be appointed to the bench in a northern state. He presided over the court until his death. Three quarters of a century would pass before another African American would hold a full-time judicial position in Massachusetts. Ruffin died from kidney disease at age 52 in 1886. His legacy continues: in 1984 the George Lewis Ruffin Society was established to support minority professionals in the Massachusetts criminal justice system and to promote understanding between minority communities and the criminal justice system.

Ruffin and other African American attorneys, author Mark Schneider notes, “played a special role within the emerging Black upper class, in that they necessarily interacted more with White society than other professionals. . . . These were distinguished men unalterably committed to the antislavery tradition, who rose with their race.”[3] The inscription on George Ruffin’s grave beneath the graceful Japanese maple tree on Indian Ridge Path affirms that he was: “The First Colored Judge Appointed in the North.” On the opposite side his epitaph reads: “He did his duty bravely, And no one trust betrayed.”

George Lewis Ruffin is buried in Lot 4960 on Indian Ridge Path.

This is a stop on Mount Auburn’s

African American Heritage Trail

FOOTNOTES:

[1] Stephen Kantrowitz, More Than Freedom: Fighting for Black Citizenship in a White Republic, 1829-1889. New York: The Penguin Press, 2012, p. 4.

[2] George Ruffin, “Introduction,” in Frederick Douglass, The Autobiography of Frederick Douglass, Hartford: Park, 1882, p. 21.

[3] Mark Schneider, Boston Confronts Jim Crow, 1890-1920. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1997, p. 197.

TOP IMAGE:

George Lewis Ruffin. Courtesy of Historical & Special Collections, Harvard Law School Library.

Leave a Reply to Lisa Francavilla Cancel reply